Mysterious Voynich manuscript is in HEBREW, say scientists using AI

An ancient manuscript that has baffled scholars for centuries is on the verge of being deciphered after computing scientists discovered it was written in Hebrew.

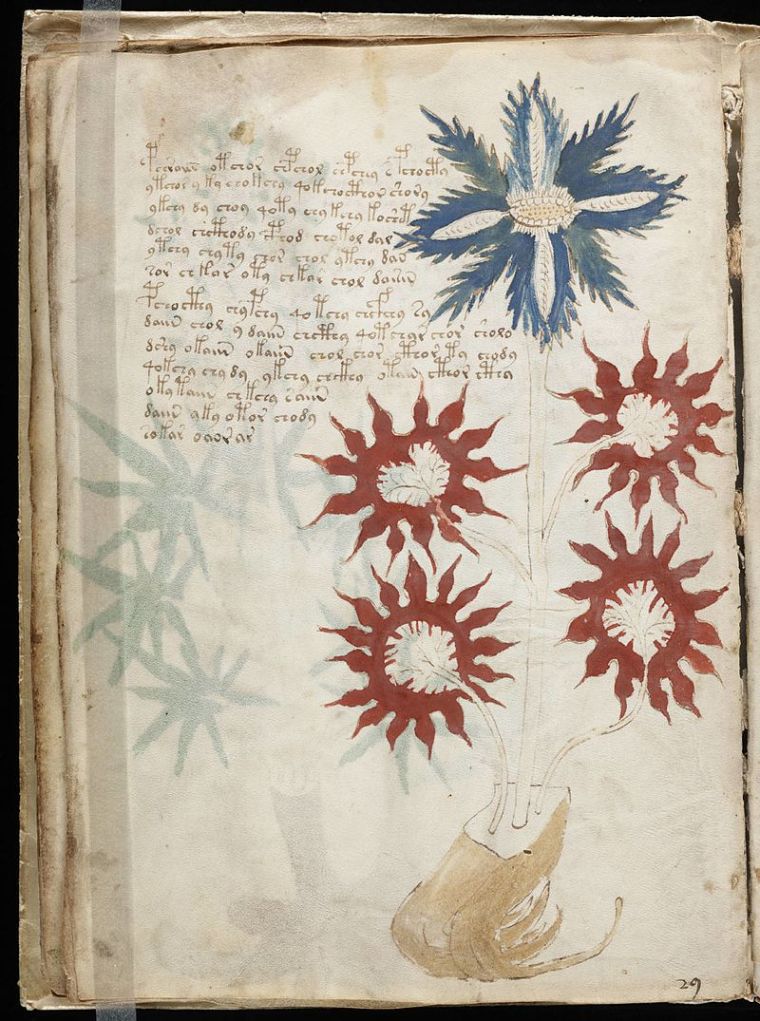

The 15th-century Voynich manuscript, comprising hundreds of vellum pages with illustrations, was discovered in the 19th century but was written in an unknown code relating to an unknown language. Scholars who have worked on it have failed to read it and some have dismissed it as gibberish or simply a fake. However, it is generally believed to date from the early 1400's and to have been written during the Italian Renaissance in Northern Italy.

It has defeated cryptographers for years, including British and American codebreakers from the First and Second World Wars.

Now, however, scientists at the University of Alberta are on the verge of cracking the code after using computers to identify its language of origin.

Prof Greg Kondrak and graduate student Bradley Hauer set out to use computers for decoding the ambiguities in human language using the Voynich manuscript as a case study.

They used samples of 400 different languages from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to identify the encoded language, originally suspecting it was Arabic.

After running their algorithms, it turned out that the most likely language was Hebrew.

'That was surprising,' said Kondrak. 'And just saying "this is Hebrew" is the first step. The next step is how do we decipher it.'

Kondrak said: 'It turned out that over 80 per cent of the words were in a Hebrew dictionary, but we didn't know if they made sense together.'

After an initial approach to Hebrew scholars failed to come up with a reading that made sense, the scientists turned to Google Translate. 'It came up with a sentence that is grammatical, and you can interpret it,' said Kondrak.

The sentence was: 'She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people.'

'It's a kind of strange sentence to start a manuscript but it definitely makes sense,' he said.

Kondrak and Hauer applied their method to a section of the manuscript containing drawings of plants and came up with words that 'would not be out of place in a mediaeval herbal', such as the Hebrew words for 'narrow', 'farmer', 'light', 'air' and 'fire'.

They say their method 'can only be a starting point for scholars that are well-versed in the given language and historical period'.