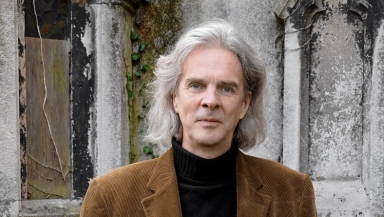

Peter Stanford grew up going to church in Liverpool, but it was his time as a journalist for the Catholic press that started to awaken a deeper love for that special place churches have in both the community and the British landscape.

That love only grew when his family rented a holiday home in Norfolk, leading him to stumble into the stunning 14th century church, St Mary's South Creake.

That first visit one rainy day, while looking for a way to amuse his bored children, sparked what has become a lifelong passion for visiting medieval churches the length and breadth of the UK - a hobby also known as "church crawling".

It's a story he tells in his new book "If These Stones Could Talk", which also explores the special and unique link with the past that ancient churches give us.

Peter speaks to Christian Today about the importance of safeguarding these churches for future generations and why he hopes more people will take the time to venture inside them.

CT: How did you get into church crawling?

Peter: It was Diarmaid MacCulloch, author of "A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years", who actually coined the phrase 'church crawling'.

Upon leaving university, I worked for The Tablet and the Catholic Herald where I was editor for four years. That took me into lots of churches reporting on what they were doing in terms of their outreach, and I was so impressed by their work for the common good in society.

That's what started me off. But I really got into after my family went on holiday to north Norfolk when my kids were still very small. We rented a little house in a village near the coast and of course, being England, instead of being nice and sunny it was pouring with rain and the children were restless. I found a leaflet in the house about a nearby 14th century church, St Mary's South Creake, and got the kids together with their colouring books and pens to get them out the house.

Inside, I found the most fabulous angel roof, which was installed to celebrate the English victory at the Battle of Agincourt in France during the Hundred Years' War - as if the angels would have come down to help the English bowmen kill lots of French people with their arrows! And so they built this ceiling that even survived the Reformation.

Of course it carried on raining for the rest of our holiday and so we filled up the time visiting lots of other churches.

CT: What is it you like so much about visiting old churches?

Peter: So many things. It teaches us about the history of the Christian faith, of people and what people believe - and that's essentially what my book is about; it's a people's history told through buildings and what those people believed.

Take St Mary's South Creake as an example. With the Reformation in the 16th century and the Puritans in the middle of the 17th century, lots of church buildings, particularly in East Anglia, were stripped of their 'popishness'.

Most of the stained glass inside St Mary's South Creake was smashed. And yet, they didn't take away the angels. And why didn't they take them away? It could be because they didn't have a big enough ladder to get all the way up there to remove them. But I suspect that the real reason they didn't take them down and the reason why they are still here to this day is that people found great comfort in them.

There may have been this Reformation telling churches to get rid of everything Catholic, but what you find is that on the ground, the people responded in their own different ways according to their own needs or wants. And it's those needs or wants that connect us and give us that sense that we are part of a long chain of people.

All these years later, I still like to go and sit there underneath these angels and I find it very comforting. I have the same feelings as those people in the 16th century who decided they didn't want their angels smashed off the ceiling. We have the same thought and it links us back to that point in history. We become part of this chain of belief and of people just trying to find our way in the world.

CT: You seem to have a deep respect for the medieval age.

Peter: One of the things I really dislike about the 21st century is that we're all encouraged to think we're so incredibly important. We think our society is so sophisticated and clever, and it's all about me, me, me and the individual. We look back and use the word 'medieval' as if it's an insult. We say things like 'oh, that's so medieval' as if it's a bad thing! But medieval people really had a clear-sighted view of many things that we've lost sight of.

So I like the sense of perspective that these ancient buildings give us - that we are just little grains of sand in the tide of history. We're small in a historical way, in a societal way, in a world culture way, and also in an individual way.

CT: You note in the introduction to your book that Britain is not a particularly churchy nation anymore and that church crawlers are a bit of a rare breed. Why do you think so many people do not step into our ancient churches?

Peter: For one thing, there's been a drift away from church attendance within mainstream Christianity - and there are all sorts of very good reasons for that. Thinking about my own Church, the Catholic Church, it has disgraced itself in lots of ways by covering up the abuse of children and not treating women equally. There are lots of reasons why people feel alienated from it.

There are lots of people who don't want to sign up to a denomination or institution, but who have a very strong religious sense, and they are exactly the sort of people who could benefit from going into churches but they probably don't because they associate church buildings so much with the institution and because of that they think, well if I go in there, then I'll have to be part of it.

Then there are people with no belief at all and they might worry that if they go into a church they will be disrupting something or they will be asked questions or asked to give money. Of course that's not the case at all!

There are these extraordinary treasures in the middle of our communities that are free to go in with no obligation and most of the time you'll have them to yourself. We should use them more and benefit from them more. It's not about becoming more religious but they are part of who we are as a country.

We can't think of the stereotypical image of the English countryside or market town and city without thinking of church spires. They mark out the landscape of our nation, particularly in the countryside. You can walk through fields and orientate yourself by looking out for a spire. They are part of us and we should use them.

But I think what needs to happen in these much more secular, sceptical times is to help people detach church with a lower case 'c' from 'the Church' with a capital 'C', so that people feel able to go in and explore and enjoy and be enlightened by these fantastic church buildings without having to be at all religious or part of the institution of 'the Church' with a capital 'C'.

CT: Do you think we are doing enough as a nation to preserve our ancient churches?

Peter: Encouraging people to go in and explore our churches is easier said than done because someone has to pay for the upkeep of these churches and that's where things get difficult. There might be only a handful of people joining the actual services, and all the while the parish councils are trying to maintain these medieval churches and it's completely beyond them.

There are various initiatives and charities like the Churches Conservation Trust and the National Churches Trust, but really, if we want these places to be preserved as part of our landscape and our historical record then the state needs to be involved. They can't take them off the Church of England but the Church of England should be able to access some support that recognises that these church buildings have a significance that goes beyond their immediate congregation.

Rather disappointingly the amount of money for this has only been reduced over the years. For example, a whole part of the National Lottery Heritage Fund that used to go to churches has now been abandoned.

So we're not doing a good job in looking after these churches and that's preventing society from being able to get the full benefit of these buildings. Many of these churches are a mess inside but they are nonetheless the most stunning, spectacular churches. As a taxpayer I'd be very happy for a percentage of my taxes to go towards looking after them.

CT: Your book starts with the first century so it's going really far back into British Christianity. How much do we know about that time?

Peter: It does get quite tricky in the first five centuries but what we do know is that when the Romans conquered Britannia in 43 AD, the Roman officials and military leaders who came over and controlled the colony absolutely would not have been Christian because the religion of the Roman Empire centred on this pantheon of gods and emperor worship, and so they were not allowed to associate with any other religion.

But we do know that there were lots of Christians in Rome, certainly in the second half of the first century, and that there were a lot of Christians in Gaul (modern-day France), and that a lot of the troops that came over to conquer Britannia were from Gaul. So there would have been Christians among them. There would also have been Christians coming on the coattails of the Roman colonists - traders, for example.

And while we don't have Christian buildings from that time, we do have places associated with the legends that developed centuries later. Glastonbury, for example, is associated with Aristobulus of Britannia as well as Joseph of Arimathea and the Glastonbury Thorn, which in turn are connected to the hymn we sing today, "Jerusalem".

But the first proper church that you can actually still stand in is St Martin's Canterbury, which dates to the 5th century before Augustine came. What I love about that church is that there is a particular bit you can stand in between the nave and chancel where the original 2nd century Roman bricks are and you can put your hand there and in that moment be carried back 1,800 years. Because we know that at some point King Ethelbert of Kent and Queen Bertha, who welcomed Augustine and Paulinus his deacon, all stood in that spot.

There is this really strong sense of standing in the footsteps, and walking in the footsteps, of these people who lived centuries ago. You have to stand there and think about it for a moment: I'm touching 1,800 years of history, how extraordinary.

CT: Do you have a favourite among the churches you've encountered over all your years of church crawling?

Peter: I used to spend summers in Rome and Santa Sabina, an early Christian basilica, is just breathtakingly beautiful and extraordinary.

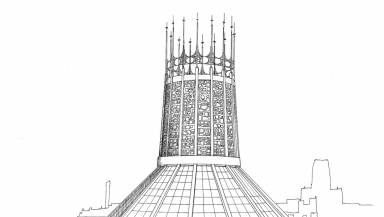

Closer to home, the church I have the most long-term emotional connection with is Liverpool's Catholic Cathedral which I think as modern churches go is yet to be bettered. If you go in there at any time of the day, it is shaped like a rocket and the bell tower is in the centre with John Piper stained glass all around. As the light sweeps around it makes the most extraordinary colours and shades, and my parents are in the book of remembrance.

But the one I return to most often is an intriguing church you have to walk about two miles through fields to get to. All Saints Waterden sits in the middle of a Norfolk field - literally in the middle of nowhere! And dates back to the 10th or 11th century. They only have about three services a year but it's a church that is a mystery - you can't quite work out what it's history is. But I like nothing more than to walk over and just to sit there.

CT: Do you have a favourite period in Britain's ecclesiastical history?

Peter: I'm quite partial to a Norman church. The Normans built their churches in a particular way to impose their authority so they look slightly fortress-like but they combine the fortress and the beauty quite well. Later on, churches get a bit twiddly with the gothic perpendicular so it's early Norman churches that do it for me.