A 'miracle spring' in eastern Fiji supposedly possesses healing properties, cited by many in the majority Christian country as a gift from God. The remedial waters have now attracted global attention – so is it real 'healing' or a hoax?

The poor town of Natadradave has become a site of pilgrimage to thousands of invalids seeking its 'miracle spring', according to the report by The Guardian today.

'In one month, maybe 50,000 people visit,' said Menausi Druguvale, the local who discovered the spring two years ago. He had sought healing after suffering conjunctivitis and losing much of his vision. He claims his eyes were cleared after showering in the source of the water, in the mountains of Fiji's Western Division, after which he spread the word to locals and soon sparked international interest.

'Some people will come in a wheelchair, some people come by ambulance. I massage the mud into people's skin after they have showered and drunk the water.'

'It works [the healing water]. Every single time.'

The Facebook group Natadrave Testimonies, which has nearly 60,000 members, documents numerous accounts of healing at the spring. One story tells of a man, physically impaired by a stroke and forced to walk on crutches, but no longer needing his crutches after just one 'session' in the bath. Claims of healing cover a range of conditions, from skin and muscle issues to mental illness, paralysis and cancer. The locals forbid the monetisation of the spring for financial gain, wary that any cash exchanges would compromise the blessing of the waters. Many who visit also bottle up the water in order to deliver its healing powers to those unable to travel.

Many in Fiji see the spring as a gift from God, particularly after the historically severe Cyclone Winston struck devastated the island in 2016. The success of the spring has prompted the Fijian government to gift housing grants to the village, only adding to the local sense of blessing.

'But being famous has made us more exposed too,' said resident Esili Tukana. 'Some people who come are not honest. We have heard stories of scammers, people have bottled and tried to sell the water in Suva, Nadi and overseas. And that is against the spirit of the water. It won't work if it's sold.'

Professor Steve E Hrudey, an expert in water, toxicology and the environment at the University of Alberta told The Guardian said that though he was sceptical of water itself having proven healing power, purified water could have 'biological effects' as a solvent (depending on what is dissolved in it), and the placebo factor remained potent.

'By definition', he said, 'claims of miracles mean just that, they rely on faith rather than scientific evidence, so I will not hold my breath in anticipation that Fiji has discovered a new cure for conjunctivitis or any other illness.'

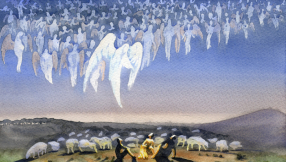

The notion of the miraculous is obviously not foreign to the story of Christian Scripture of indeed the history of the church. In 2 Kings 5 the soldier Namaan is healed of leprosy after washing seven times in the river Jordan. The prophecy of Ezekiel 47 speaks somewhat curiously of 'healing waters', and in the New Testament John 5 depicts numerous invalids who hoped they might find healing from the pool named Bethseda in Jerusalem.

Today, several claim to have been healed by miraculous water flowing from a spring in Lourdes, France. The famous Catholic site is a common place of pilgrimage, with around six million a year making the trip.

But these miraculous springs, like the notion of healing in general, are controversial and divisive within the church. Some may be wary of superstition, applying 'magical' properties to earthly objects rather than seeking the Holy Spirit, or merely whipping up a frenzy, exacerbated by the placebo effect, that misleads the vulnerable sick and poor. Others may shy away from such scepticism, and say that if there are witnesses to contemporary healing, such as in Fiji, then it must be celebrated and sought for as long as the blessing lasts.

Peter May is a retired GP in Southampton who has spent much of his life researching the modern phenomenon of 'healing' and its place in the church – he remains open to the possibility of divine intervention but is sceptical of many modern claims to the miraculous. In the extensive 2017 Science and Belief journal article titled 'Miracles in Medicine' he covers Lourdes in particular, and challenges several of the famous 'healing' claims officially made from there. Even the most popular claimed healing from Lourdes left him, and other medical experts, unconvinced. He posits that often healing is cited when in truth the original malady was misdiagnosed (due to lack of technology, such as MRI scans, at the time), or was just recovered from naturally eg by spontaneous remission.

The debate goes on. What is clear is that 'miracle springs' present a puzzle – for scientists, theologians, or the needy, sick and lame.