Ireland's new prime minister, Leo Varadkar, announced in his first speech as the country's leader on Tuesday that a referendum on its constitutional ban on abortion is planned for May or June 2018, just months before Pope Francis is due to visit the Catholic-majority country.

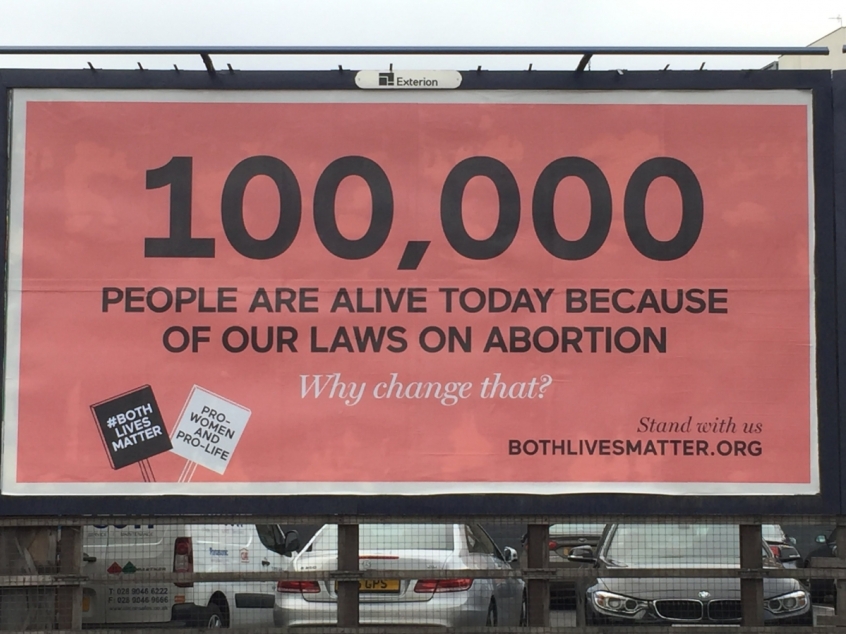

As it stands, Ireland is one of the last European countries where abortion remains illegal in all cases, except those where the mother's life is clearly endangered. The eighth amendment of Ireland's constitution holds that mothers and unborn children have an equal right to life. Therefore, for any changes to the laws regarding abortion, the country's constitution itself must be altered which, in Ireland, requires a popular vote.

In an interview with Christian Today, Nick Park, spokesperson for the Evangelical Alliance of Ireland said: 'We have known this was coming for some time. But what will be crucial is the wording of the actual referendum because surveys have shown that the majority of Irish people oppose abortion on demand, but want to see it legalised for limited circumstances.'

According to a survey of Irish voters conducted by Ipsos MRBI in May, 82 per cent agreed that abortion should be allowed in cases where there was a serious risk to a woman's health; 76 per cent agreed for cases where the pregnancy was the result of rape, 72 per cent agreed for cases where a woman's mental health is at serious risk and 67 per cent believed abortion should be allowed when there is a foetal abnormality likely to lead to death.

However, 67 per cent were opposed to abortion on request and 68 per cent believed abortion should not be legal for cases where a woman lacks financial or family support. Another poll, by Behavior and Attitudes for the Sunday Times in late April found 61 per cent of Irish voters opposed to a situation in which abortion was legally available, regardless of the reasons for which the procedure was sought out. Further, 58 per cent also opposed abortion being permitted because the parents would struggle to financially support the child.

This means that the phrasing of the referendum may well determine how far any change to the law properly represents the nuance of popular feeling towards the issue. If abortion were allowed in Ireland only in specific situations, it would be distinct from most European countries where the legality of an abortion does not depend on the specifics of the situation.

Park, however, fears that 'the pro-abortion lobby will try to exploit this situation [where most Irish people believe that abortion should be permitted in certain situations but not available on request] by exploiting very emotive cases, and in doing so, remove the constitutional protection from all unborn children'.

Unrestricted abortion up to the 12<sup>th week of pregnancy, with certain restrictions after that was proposed by the Irish Citizens' Assembly – a special committee composed of 99 members of the public selected at random.

When asked about whether it was appropriate for Christian moral values to be imposed on society at large, Park said that the Evangelical Alliance of Ireland is not approaching it as a purely religious or 'cultural war issue', but a human rights one. He noted that the organisation's campaigns in anticipation of the referendum would centre on 'a positive affirmation of all life, including that of the unborn'.

He drew a comparison with other Christian efforts to defend the rights of vulnerable and oppressed groups – William Wilberforce's campaign for the abolition of slavery and Martin Luther King's fight for civil rights in the U.S being the most notable examples. 'Throughout history, human rights have been violated when people try to say only certain groups deserve them.' Women, children, and people of colour have all at various times been viewed as of inferior value to white adult males, traditionally those who held the legislative power, and therefore requiring less legal protection.

'It is part of the general progression of history for these rights to be extended to previously excluded groups and it is in our humanitarian tradition as evangelical Christians to extend human rights to all groups, including the unborn,' Park continued. To that end, the Evangelical Alliance of Ireland has published two books on abortion from a human rights, rather than an explicitly Christian, perspective – Birth Equality and The Gospel & Human Rights.

The same perspective is being taken by other pro-life groups. This month, Ireland's Pro-Life Campaign tweeted: 'Usually referendums add protection to human rights. #RepealThe8th would strip the unborn child of all meaningful protections.'

Atheists For 8th also tweeted that the amendment as it stands 'recognises that during pregnancy, there are two lives that must be protected. Instead of #repealthe8th, let's #Loveboth'.

The 8th amendment was decided by a referendum in 1983, when 67 per cent of voters approved it, but it was broadened in a 1992 referendum, which made it legal for women to travel to another jurisdiction to have an abortion and for information about abortion services abroad to be provided to Irish citizens. According to UK government statistics, nearly 4,000 women from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland traveled to England and Wales to receive abortions in 2016.