In this latest installment of their Jewish-Christian dialogue, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and Hebrew scholar Dr Irene Lancaster discuss their different perspectives of Jesus' teachings in the Sermon on the Mount and how a Jewish audience might have understood them.

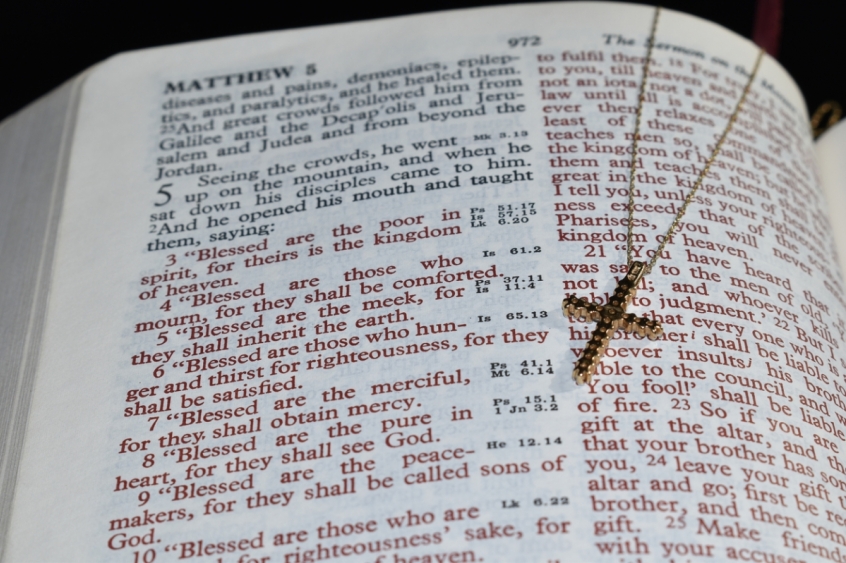

Dr Williams: The Sermon on the Mount, in the 5th to 7th chapters of St Matthew's Gospel, is the longest continuous summary of Jesus' teaching in the first three gospels (not as long as the 'Farewell Discourses' at the Last Supper reported only in John's Gospel), and much of it also appears in Luke's Gospel. Matthew's version is probably the earlier one, slightly closer to what may be the original Aramaic. It isn't surprising that it's usually seen as an account of the essential teaching of Jesus of Nazareth - although it would be a mistake to imagine that it records a single extended discourse by Jesus on one occasion. The variations between Matthew and Luke suggest that material may have been used more than once in slightly different forms and so has survived in different wordings.

But if it's the heart of Jesus' teaching, it's essential to be clear about its meaning. It contains some sharp criticisms of people whose religious practice is only skin-deep, and it has a series of contrasts between 'what was said to the people of old time' and 'what I say to you.' Both these things have often led Christians to treat the Sermon as defining the difference between Judaism and Christianity, and to read it as a critique of Jewish 'legalism'.

But this is a disastrous mistake. In this brief survey of the text, we shall aim to show how the text presents a Jesus who is deeply engaged with Jewish Scripture, Jewish identity and the question of how the Torah should be observed. He is not speaking to 'Christians' – there weren't any when he spoke these words. He was speaking to fellow-Jews. What is new about the Sermon is not the teaching of a new religion: Jesus did not think he was founding a new religion but offering a new way of being Jewish. The newness of Christian faith lies in the fact that, with the death of Jesus and the conviction of the apostles that Jesus had been raised from death by God, the implications of these stories led the community of his followers gradually to separate from the Jewish world. And that is another story. But even with this long and tragic separation, it is crucial to remember that the Jesus we encounter in these chapters is a Jew speaking to Jews – and that if Christians are to be faithful to what he says, they have to understand what the words meant in their Jewish context.

We'll be looking at three sections of the text, just to illustrate this. First, the 'Beatitudes', the opening sequence of verses saying who will be inheritors of God's blessing, who will (in a familiar Jewish phrase) have a share in the 'age that is coming', the 'olam ha-ba); second, the series of apparent contrasts between the text of Torah and the teaching of Jesus; and third, the sections about prayer and trust in God.

But to start with, Irene, what strikes you as Jewish reader when you look at the text of the Beatitudes, for example?

Irene: When I first read the Beatitudes I simply felt that out of their NT context they had more in common with Jewish teachings of the time, the teachings preserved in the Mishnah. Especially important is the very popular (because available in our daily prayer book, both in Hebrew and in the vernacular, and studied in detail throughout the year) Pirke Avot . This is a difficult title to translate – the most popular rendition in English being 'Ethics of the Fathers'. But what it really means is 'Sayings from our predecessors', or even 'Deep down, what are our predecessors actually saying?', which is a bit unwieldy, I'm sure you agree. But the word 'Av', as well as 'father', can mean 'origin', or 'principle'. A good title for our own day, even if it is a Mishnaic Tractate, is 'Back to basics'. And this is what the early rabbis are doing, and also what, it seems to me, Jesus is saying as well.

You mentioned the original Aramaic - did Jesus deliver these in Aramaic, which is very close to Hebrew, or might he have spoken in Greek? If Matthew was Jewish, did he realise how much Jesus is simply reiterating Jewish teachings from the Oral Law, ie. the Mishnah, or did he think that these reiterations of basic Jewish truths were actually something new? Did he know Hebrew? Luke of course isn't Jewish, though he certainly knows the Hebrew scriptures in Greek translation. But I'm left wondering about the context in which the writers of these gospels were working and how much knowledge of the Torah they took for granted.

1) 'Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.' To me 'the poor in spirit' are those of us who are down and depressed. This does not necessarily refer only to people who are materially poor, because the Jewish people have usually been poor: as soon as they felt part of any society they lived in, they were forced, either by expulsion, or murder, to leave. They are always having to start again some way or the other. So, this is all about being in a position where the spirit is crushed. It's no accident that Jews have always been in the forefront of psychiatry and therapy, helping those for whom life does not have meaning any more to re-envision their reality and to see the small things of life in a new light. This is why family and music mean so much to Jews. Family and music are often the only things that Jews have. And of course, books and thought, because even in prison, it is difficult to take thought away from you.

2) 'Blessed are they who mourn, for they will be comforted.' Many converts to Judaism have told me that the best thing about Judaism is how mourners are comforted through the shiva system, when the community take over for seven days and the mourner's needs are fully met by others 24 hours a day. Rabbis often excel at this kind of comforting. Mine certainly does and I've written about this previously for Christian Today. But then, there is so much to mourn, given the constant attacks on the Jewish community – whether physical, intellectual or spiritual. The Christian Church which grew out of the religion of Jesus has probably done more than anyone to make Jews mourn.

3) 'Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.' It could of course be 'inherit the Land' - i.e. the Land of Israel. And that is a reminder that in the Hebrew Scriptures, 'inheriting the Land' is a central aspect of the divine promise (look at Psalm 37, for example). It's possible that Jesus's words were an implicit challenge to the Romans who occupied the Land of Israel at the time. But the Romans are long gone, and Israel is now a sovereign State once again, a true 'light to the gentiles'. I read these words as saying that arrogance comes before a fall – if not in this world, certainly in the world to come. And the area of the Temple is always with us, not simply the Kotel (Western Wall) where so many pray, and a magnet for pilgrims from all over the world, but also the Temple Mount itself, built at the very spot where Isaac was replaced as a sacrifice by the ram in a thicket, whose horn we blow at the major autumn festivals of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur (Jewish New Year and the Day of Atonement).

4) Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be filled.' This is of course pure Isaiah 55, as well as the key point of the Pesach Seder, and the root of Jewish thought – with the Hebrew tzedek depicting both justice and mercy. This is why the Texan rabbi opened the door to the Muslim stranger from Blackburn, to feed and comfort him, and was then himself threatened with murder. This was the Chabad rabbi in Mumbai a number of years ago. Massacred with his family, again by a Muslim who was asking for food and shelter in Shul. This is the paradigm Jewish behaviour. Others know that hospitality is key Jewish behaviour and .....

5) 'Blessed are the merciful, for they shall know mercy.' This is of course not always the case in this world. The Jewish people have always been merciful and haven't always received mercy in return. But maybe Jesus is alluding once again to the world to come.

6) 'Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see G-d.' Can we see G-d and live? Even our greatest prophet Moses could only see G-d's 'back', as stated in Exodus 33 – G-d's 'glory' not being G-d Himself. This is, I think, a real divergence in the two religions. On the other hand, as Tevye would say, maybe it means that if you are pure in heart you are behaving as G-d wants, and in this sense you 'shall see G-d.'

7) 'Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of G-d.' Another divergence. I think this relates to family relationships and also to one's near neighbours. Jews do not believe that you can appease Hitler. Nor do we believe that we have to allow ourselves to be killed for the goal of 'peace'. I feel that this principle may have been misunderstood by Christians for 2000 years.

8) 'Blessed are they who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for they shall be called children of G-d.' This adage has been the reality of the Jewish people for nearly 4000 years. It is extremely difficult to practise one's Judaism and many have been persecuted for carrying on with this. In modern times, we only have to think of Jews in Tsarist Russia, or Soviet Jews under Communism, or Jews during the Holocaust, and in present-day Europe, the attitudes of all the major institutions of the West – including, it now seems, in North America. So, maybe this is what Jesus had in mind. However, for Jews, the adage reinforces the belief that we should expect persecution for 'righteousness' - not for no reason at all. At the end of the day, even though it is stated in the Talmud that it is incumbent on all Jews to obey the law of the land ('the law of the land is the law', echoing Jeremiah 29:7), there are three cases, nevertheless, where we have to be prepared to lay down our lives in diaspora rather than obey the law of the land. There is definitely a concept in Judaism of there being a higher law than the law of the State. The three cases are as follows and are more prevalent than ever in the 21<sup>st century. This is if we are forced to commit or publicly condone murder (including abortion on demand, or assisted dying), idolatry (worshipping political or religious leaders and parties, footballers, food, artists, wealth etc) or partaking in or condoning sexual immorality.

Dr Williams: That's very illuminating indeed, especially the comparisons with the Pirke Avoth. I think we can assume at least that Matthew and Luke knew the Greek Old Testament, and they do clearly preserve the saying of Jesus that he has not come to destroy but to fulfil, and that the Torah itself will never pass away. One quick point on 'seeing God' - the texts in Exodus say both that no-one can see God and live and that (Ex. 24) the elders of Israel 'beheld God', as well as recording that Moses spoke to God face to face. Some of the Psalms likewise use the language of seeing God. Both in Christian and in Jewish teaching, there is a tradition of distinguishing between the divine glory that can be seen and the actual essence of God which is beyond sight and thought. Presumably, seeing God in this context is a promise that those who do God's will 'see' what God desires or commands and also see something of the vision of his glory?

But the main point I think we can agree on is that Jesus is seeking to answer the question (which many were asking in his day), 'What's the essential thing about being a member of God's people?' And he answers in terms that are very familiar from the Psalms and the Prophets. God's people are 'poor in spirit' (compare Psalms 9 and 10, for example) because they don't trust in their own resources and strength alone; it is these trustful people who, although here and now they may be 'mourning' for their powerlessness, will inherit the Land, not those who flaunt their power or riches. They are humble and merciful, and eager to see justice prevail, and so they will be known as children of God and will be able to bear the glory and terror of the vision of God – to 'see God' but also to 'be seen' by God (as in Ps. 84). The true Israelite here is the one who is both passionate for justice and also conscious that nothing is done without God's help; real obedience to the Torah means giving up self-satisfaction and self-sufficiency. It also means - as you have stressed - being willing to risk persecution on account of your commitment to God's will and commands.

So here is Jesus, like the prophets, calling the Jewish people to remember who they really are. And the same goes for the sequence about 'you have heard that it was said.' Irene, you'll have heard all too many sermons and talks about 'Jewish legalism', with people trying to contrast Jewish 'law' and Christian 'gospel'.

Irene: Yes, Rowan, this crude legalism attributed to us Jews is simply a figment of the imagination. For example, images like going through 'the eye of a needle' and 'turning the other cheek' appear in the Mishnah (written at around the same time as the Sermon on the Mount). The reference to 'an eye for an eye' in Torah , for example, has a very different meaning from the one usually taken for granted by Christians. In Jewish interpretation, 'an eye for an eye' means a fair monetary compensation for injury caused. The medieval Jewish commentator, Abraham ibn Ezra (1089-1164) explains the reasoning behind this interpretation very well. What if you are short-sighted, for instance? How can we assess the value of an eye, when no two eyes are the same. Based in ancient Jewish scholarly commentary, we know that there are 'gaps in the Biblical text', which have to be filled in. Certain phrases have been deliberately distorted as a stick with which to beat the Jews, so it is essential to explain yet again that not everything should be taken literally. The Bible is not a technical manual, but the word of G-d. And for us, this means that it has to be interpreted by humans in order to make sense properly.

But Christian sermons on this still repeat the stereotypes. Remember Pope Francis's sermon in August 2021, where he repeated St Paul's phrase about 'the Law' not being able to give life'. Reusing this phrase outside of its original context implies that Judaism is dead as a religion. I should think that Pope John XXIII and Pope John Paul II, who both did so much to repair the gulf between Jews and Christians, must be turning in their graves at this heresy in the mouth of their successor! It feels as though exactly 60 years of repentance by the Catholic Church for their execrable and unforgivable behaviour towards the people from whom Jesus came have been swept away in one ill-thought remark.

Dr Williams: Jesus is insistent that he is in no way denying the claims of Torah. But he is saying, 'What are the internal states of mind that make it more likely that we'll keep the commandments? Murder comes from anger we can't control. Adultery comes from sexual greed we can't control. So start with recognising and working on these inner passions, and the commandments make more sense.' Like the prophet Jeremiah (31.34), Jesus is speaking of a situation in which the Torah is 'written in our hearts' so deeply that we no longer need to remind one another of it in words.

So when he says that the 'righteousness' of his followers must be greater than that of scribes and Pharisees, I don't think he is writing off the legal experts as a bunch of hypocrites – he's saying that there is a level of obedience to Torah that is more important than even the most loving and exact external observance, and it's in the change of heart that underpins outward behaviour. As Jesus says elsewhere in Matthew's Gospel (ch.23), it's not about not keeping the lesser rules, but about not using your faithfulness to these details as an alibi for the greater demands of Torah – defined in that passage as 'justice, mercy and trust'. And when in that later passage he attacks 'scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites', we shouldn't understand this as implying that people are hypocrites because they are scribes and Pharisees; the Greek text is better understood as attacking those who hypocritically pretend to be scribes and Pharisees. After all, his hearers would have thought of the title of Pharisee as a name of honour.

I think you get just a flavour of this if you imagine some dedicated traditional Roman Catholic or Pentecostalist saying to me 'You're just one of those Anglican hypocrites!' (because they will assume that all members of the Church of England are probably hypocrites); and then someone else, who respected the Church of England saying, 'Call yourself an Anglican! You're just a hypocrite!'

The point is that what Jesus is saying is in its context more like the latter than the former.

Irene: Calling someone a 'Pharisee is a typical Anglican trope against Jews, though, isn't it. I think of the famous occasion when Archbishop Robert Runcie called Margaret Thatcher 'Pharisaical.' And the then Chief Rabbi, Lord Jacobovits, attacked the Archbishop publicly for his use of an anti-Semitic stereotype. Archbishop Runcie must have come across quite a few Jews as fellow students in his school at Liverpool - the same school I attended. No excuse for this. 'Anglican' is not really a loaded term in the culture we live in. 'Pharisee' is definitely loaded - and so is 'Jew' for that matter. What's interesting is that Pharisees were the radical reinterpreters, who democratized Judaism if anything, and emphasized learning and good deed, prayer and humility above wealth, status and the priesthood. To many of us, Christianity is therefore now the 'Pharisaical' religion in the negative sense used by Runcie - in love with externals, insensitive to the needs of ordinary people.

Dr Williams: There was a famous Baptist New Testament scholar in Oxford years ago who always said to his students that he hoped that if they'd been around in the time of Jesus, they'd all have been Pharisees, because that was what serious Jews wanted to be. If Jesus attacks Pharisees (and remember he lives in a context where fierce religious controversy is an everyday thing and people don't always bother about being polite! These criticisms are mild stuff compared with the vitriol you find in the Dead Sea Scrolls about the religious leaders of the day), it's because they represented the best in the Jewish world he knew, and his own teachings are thoroughly in accord with much Pharisaic doctrine.

Irene: The Baptist NT scholar appears to be a one off. I wonder who he was and if any of his books are available. I wouldn't mind reading them. I have never ever come across a Christian before now who has anything positive to say about the Pharisees. The root of the Hebrew word is simply to do with 'interpretation' and 'scrutiny'. I really don't know what is offensive to Christians about the Hebrew word p-r-s.

Dr Williams: He was a Welsh scholar called Winton Thomas, who did a lot of work on the Hebrew text of the Book of Isaiah.

Now finally, there's the teaching about prayer. It would be really helpful to hear a bit about what strikes you here from a Jewish perspective.

Irene: Quite a few Jewish scholars have suggested to me that the Lord's Prayer originates in our own Avinu Malkenu, 'Our Father, our King ...' Regarding dialogue, we also pray in our Alenu Prayer, as put so beautifully by my friend, Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen of Haifa (1927-2016), son of the Nazir of Jerusalem, in his own biography, which he asked me to translate into English:

'This famous core prayer of ours describes two stages or approaches: disassociation and connection. On the fact of it, these two approaches appear to contradict each other. However, on a deeper level, they can be easily reconciled and, in fact, complement and supplement each other.

At the start of the Alenu prayer, we emphatically declare our gratitude to G-d "Who has not made us like the nations of the other lands, and not placed us like the other families of the earth. He has not assigned our portion as theirs, nor our fate like that of their multitude."

These words depict the first stage or path of our dialogue journey.

The second stage or path is described in the following lines of the prayer's second paragraph: "We therefore place our hope in You, oh Lord our G-d, to see speedily the strength of Your glory ... to repair the world through the Kingdom of the Almighty, and all mortals will call in Your Name... and come to know and internalize that to You alone every knee will bend and to You alone every tongue will swear allegiance ... As it is written [Zechariah 14:9], 'The Lord will then be King over the whole earth; on that day the Lord will be One and His name will be One."'

So there is no talk in Judaism of conversion in the ordinary sense, and no force or compulsion to be exercised over others; simply the hope that people will come to their senses through prayer, behaviour, thought and attitude. Through all these attributes people, whether Jewish or not, will eventually come to see the one true G-d. And in Judaism not only is there no compulsion to become Jewish, but – on the contrary – there is simply the hope that people will come to recognize the One G-d, which is actually more easily said than done. I wonder if Jesus would have agreed with this approach.

Dr Williams: Certainly the teaching of Jesus - whatever Christians have done with it - is incompatible with any violence to force people to become Christians. Jesus tells his followers to 'make all nations his disciples', and you could understand this as making sure everyone learns from them what they need to learn about God. But it is a text that has so often been misused to imply that the job of the Church is some sort of world domination rather than the unversal sharing of an understanding of God and an invitation to serve and love God.

Going back to prayer for a moment, it's is a deeply personal thing, and it is a time when each member of God's people recognises that, as part of God's people, they are God's children (compare Hosea 11, where the people of Israel as a whole are 'God's son') and so can pray to God as 'Father'. This was certainly a distinctive emphasis in Jesus' teaching and was one of the things that was most vividly remembered about it; but this should not lead us to think that he invented it. As in the rest of the Sermon, he is calling the Jewish people to take up their true inheritance and calling, by remembering that God loves them and is faithful to them as a father. The 'Lord's Prayer' is a prayer to this faithful father to support his people day by day and above all in the face of the coming time of trial, when the world is brought to judgment and the 'age that is coming' will begin. It's a prayer that the new age will soon arrive ('thy kingdom come, thy will be done') – and a prayer that when it does we shall be ready for it.

And this takes us back to where we started with the Beatitudes. God's people must live in trust, and not exaggerate their own resources and strength. This is the rock on which their future is founded. To the extent that Christians believed (and believe) that they have to live up to the same standards as the Jewish people – even if they came to believe that the 'ceremonial' law does not apply to those who are not ethnically Jews – they can hear all these words as addressed to them. But they make no sense unless we remember that they are first addressed to faithful Jews by a faithful Jew, who is in no way trying to overthrow the obligations of the covenant, only to deepen and reinforce the integrity of those called to belong to God.

Irene: Yes, this is the teaching of the Israeli national anthem – HaTikvah (The Hope). We can only be a free people if we hope in the one true G-d, who is our rock and our redeemer. We do not believe that you have to belong to the Jewish people, or be ethnically or religiously Jewish, to realize this type of hope. On the contrary, the teachings contained in our article, if followed in the spirit as well as in the letter, are there for everyone. They are Jewish teachings and Jewish teachings are always reinterpreted for the times we are living in.

Rowan, I have enjoyed writing this article on the Beatitudes with you. I hope our joint article speaks to hearts and minds at a time when the Jewish community world-wide is under threat from all sides and from every quarter.

And although the Church consists of one third of the entire world population at around 2.5 billion people, whereas the Jewish people only represent 15 million, if the Jews were to disappear, the world would be a truly desolate place, as evidenced by all those countries in Europe with formerly flourishing Jewish populations, which are now Judenrein and floundering.