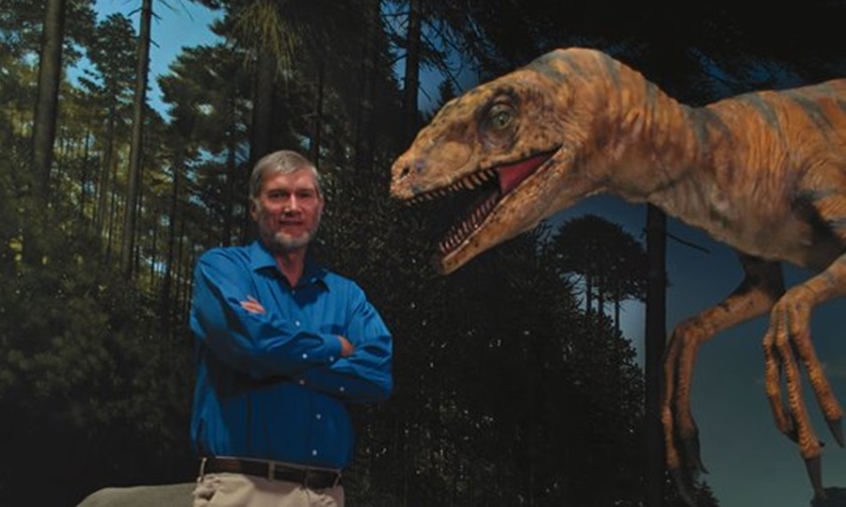

Is Tim Keller really a pagan after all? He is a highly-regarded pastor and teacher on the neo-Calvinist end of the theological spectrum, who wouldn't normally be thought of as any kind of liberal. However, he doesn't believe in a literal six-day creation, and so for hard-liners like Ken Ham, he's beyond the pale.

That's perhaps a little unfair. Interviewed by Janet Mefferd, Ham – founder of the Answers in Genesis organisation and creator of the Ark Encounter attraction – said he wasn't questioning the salvation of Keller and others who rejected the Genesis account as factual history. "It's not a salvation issue per se," he said but it is "an authority issue".

And Ham said Christians who accept evolution and the idea that the Earth is millions of years old are following "the pagan religion of this age", which is an "attempt to explain life without God".

Ham was being interviewed about a new book, How I Changed My Mind About Evolution (Monarch, £10.99). He didn't like it at all. "When you compromise God's word with millions of years and evolutionary ideas, you're no different to the Israelites who took the pagan religion of the age – or the Canaanites, or whatever – and incorporated it into their thinking," he says.

Why do they do it? "They want the respectability of the academic world and they're not going to be published in the academic world if they stand on a literal six-day creation like we do."

Keller isn't one of the contributors to the book, but he has written a thoughtful paper for the Biologos website in which he says he is fine with evolution though believes it's important to believe in a literal Adam and Eve. He concludes: "My conclusion is that Christians who are seeking to correlate Scripture and science must be a 'bigger tent' than either the anti-scientific religionists or the anti-religious scientists."

The book that started the row – or continued it – has some heavyweight contributors. Scot McKnight contributes a chapter on 'Who's Afraid of Science?' John Ortberg writes on 'Boiling Kettles and Remodeled Apes', noting that he's seen "too many young people in too many churches exposed to bad science, shoddy thinking, false claims and misguided ideas" about science, then go off to university, find they were wrong and lose their faith. British theologian NT Wright writes fascinatingly about the historical and sociological background to the whole science and religion debate, and why America is so much different from Britain. Arguments about Genesis, he says, are "bundled with larger issues, gaining a lot of their apparent heat from those larger problems rather than from their own innate difficulties".

And no less a figure than Francis Collins, director of the Human Genome Project, writes movingly about his journey to faith and how it was fed by science.

It's a very good book, and anyone who's thinking about these questions seriously needs to read it. My own cards on the table: I changed my mind about evolution too, many years ago. I think it throws up theological problems, but I can deal with those. What I can't do is rewrite science in order to make it lead to a conclusion that it just doesn't lead to. And I'm really sorry – I've never met Ken Ham, but I've seen him interviewed and he seems like a thoroughly decent bloke – but I think that's what he's doing.

In his Biologos paper, Tim Keller – and if you aren't familiar with his work, he really is a genuine conservative evangelical who has no truck with softy liberalism – asks a series of questions about evolution, the first of which goes straight to Ham's concerns about authority. Here's the q and a:

Question #1: If God used evolution to create, then we can't take Genesis 1 literally, and if we can't do that, why take any other part of the Bible literally?

Answer: The way to respect the authority of the Biblical writers is to take them as they want to be taken. Sometimes they want to be taken literally, sometimes they don't. We must listen to them, not impose our thinking and agenda on them.

I think that's exactly right. And when we do that, we can start reading Genesis as it was meant to be read, as an exhilarating, profound theological statement about God, creation and humanity. Until then we're locked in a sterile argument that stops us hearing what God is actually saying. It's time to end it.

Mark Woods is the author of Does the Bible really say that? Challenging our assumptions in the light of Scripture (Lion, £8.99). Follow him on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods