David Suchet is one of the best actors of his generation. He's a star of stage and screen, probably best known for his iconic portrayal of Agatha Christie's Poirot.

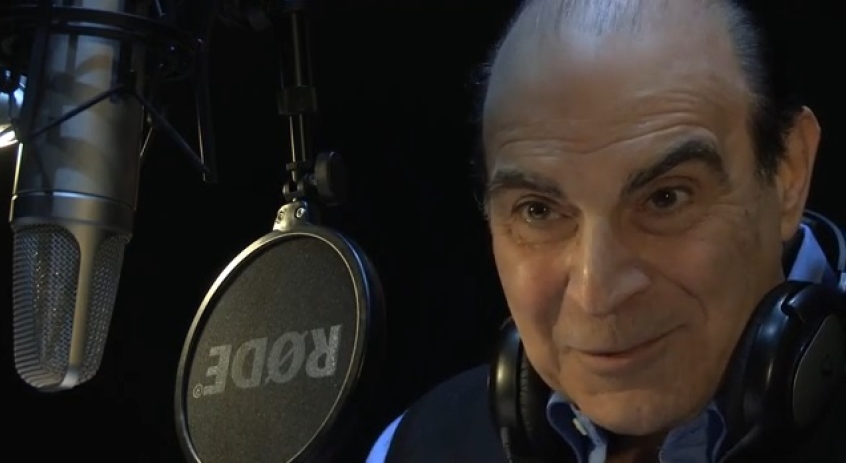

He's also a committed Christian who's passionately committed to the Bible. Suchet has recorded the whole of the New International Version – the first ever recording of the NIV by a single actor.

Available on CD and as a digital download, it now features its own dedicated Bible app which allows users to search for keywords or particular verses, read along with the audio and make notes on the text.

It was a hit for publishers Hodder when it was released 18 months ago, with total sales of 25,000 across all platforms.

It's fair to say that it was a surprise hit; no one predicted its popularity. And it's largely down to Suchet himself – who's donated his fee from the project to a fund for training Church of England priests – that the vision became a reality.

Suchet had recorded parts of the Bible before. He was inspired to push for a recording of the whole NIV by a woman from Northern Ireland with multiple sclerosis, who wrote to him saying she had listened to his recording of John's Gospel because her disease had left her partially sighted. By the time she'd finished it, she realised she had to know more about the Bible and prayed that God would help her. She woke up the next morning and she could see.

It was this sense of the need for the Bible that drove Suchet forward. Conversations with Christian TV company CTVC led to it building a recording studio in its office close to his London home, so he could walk across and record sections when he was able. Gradually the project came together.

The intensity of his engagement with the text is a stark challenge to Christians who might take the Bible more lightly – and he hopes one of the results of his work will be that it comes to life for them again.

Altogether, the 80 hours of published recordings required more than 200 hours of studio time – but that's only a fraction of his commitment to the project. Far from just turning up and reading, he studied each passage intensively beforehand. He thinks he put around 400 hours of Bible study into the whole project on top of the studio time.

At a meeting with journalists, Christian Today asked him about what he'd learned from the experience.

"I was forced to remind myself again and again that these words were written at a particular time and place for a particular people," he says. "I was constantly reminded that this is a Middle Eastern book and unless you look at it through the eyes of the Middle East you'll never understand it."

This stress on the context of the biblical books helped him to deal with one of the most challenging aspects of the reading: the bloodshed described in what's known as the "texts of terror", in which dreadful events are recounted.

"I had to deal with a God I read about who was almost genocidal," he says. "That was very hard, but reading the whole Bible and focusing on Jesus made me realise that God's plan for the world was still ongoing.

"We will never explain the mysteries of suffering, but we can think with the Psalmist, 'Why, why, why?'" And, he says, in his interpretation of those Psalms he gives the Psalmist's cry its proper voice.

He cites the verse that says, "My ways are not your ways". "We'll never understand. We have to learn to live being held in a mystery."

Suchet – who came to faith at the age of 40 – believes in expository preaching, of which he thinks there's a great lack at present. He'd also like to see the Bible taught more in schools and valued more in society: "I know that we're a multi-faith society, but we're still a Christian country. We must be warm, welcoming and loving, but we're Christian. And we're living in a very rational, secular society now. Religion doesn't mean much and it's greatly misunderstood."

He has advice for readers in church, too – he's just delivered a workshop for theological students in how to read the Bible aloud.

"Prepare everything," he says. "Failure to prepare is to be prepared to fail. If you stand up to read in public you have to do what I did – find out who it was for, what it was for, look at the language, the punctuation, compare texts, compare translations – know what it is you're reading. Is there onomatopoeia? Is there alliteration or allegory? Is it poetry or prophecy?

"I was asked to read the story of the Annunciation in Salisbury Cathedral. I made so many notes that if you'd seen it you would hardly have been able to read the text."

Suchet's reading is a great gift to the Church. It brings the Bible alive in a marvellous way – and as he points out himself, for most Christians in most of Church history, hearing it read aloud is how they would have experienced Scripture. It's only in relatively recent times that it has become a private experience. He's made it accessible not just to people who can't read text because of poor sight, but to people who are busy or who just find reading a chore – or who love the sound of a trained voice bringing out meanings they never realised were there.

But his commitment to the meaning and the value of Scripture is deeply challenging, too. If we approach it assuming we know what it means, or that we can read it aloud as we'd read anything else – a children's story, for example – we're selling it short.

As Suchet concludes: "Read it slowly, authoritatively and with confidence. It is the word of God."