Patrick Sawyer took a flight from Liberia on July 20 feeling fine, but by the time he arrived in the Nigerian capital Lagos, he had diarrhoea and vomiting and collapsed. Five days later he was dead.

More than 670 people have died and more than 1,200 people have been infected in the latest outbreak which started in south-eastern Guinea in February and has since spread to Sierra Leone and Liberia.

The idea that Ebola could spread further afield, including to the US or Europe, has put fear in the hearts of border controls around the world.

Liberian border crossings have been shut down and immigration controls have stepped up screening. But with symptoms taking days to appear, how can the spread of this epidemic be prevented?

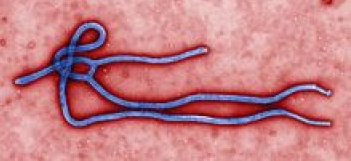

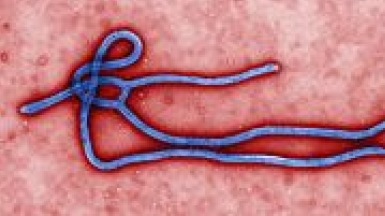

What is Ebola?

The virus was named after the Ebola River, as the original occurrence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was in a village close to the river.

It is also known as Ebola haemorrhagic fever, because many patients suffer from shock resulting from internal and external bleeding. Other symptoms initially include a headache, sore throat and muscle and joint pain, followed by vomiting and diarrhoea. It is difficult to diagnose early as the symptoms are similar to other infections, such as malaria, cholera, hepatitis and other haemorrhagic fevers.

Ebola has a 60-90% fatality rate. Those infected may not show symptoms for up to 21 days, although they commonly appear eight to ten days after infection. Once symptoms appear patients may have between a few days and a week to live.

It is highly infectious, as a small amount of the disease can prove lethal, but not especially contagious, as it requires close contact with bodily fluids, such as blood, saliva, mucus and other secretions.

There is currently no cure, so any treatment available will only relieve the symptoms. Vaccines are currently being tested but none of them are yet ready for clinical use.

Those infected are kept in isolated rooms and medical staff are disinfected before and after treating patients. A number of medical staff have also been infected in the current outbreak. Sheikh Umar Khan, a leading doctor who had treated more than 100 Ebola patients in Sierra Leone, died from the virus on Tuesday.

The natural reservoir (origin) of the virus is not yet known, but it is carried by animals, including gorillas, monkeys, fruit bats and forest antelope. It is transmitted to people by close contact with infected animals.

Traditional burial ceremonies where mourners have close contact with the deceased have been known to spread the disease.

Men who have recovered from the disease can transmit the virus through their semen for up to seven weeks after their symptoms have passed.

There are five different strains of the virus. Four of them are deadly, but the fifth, the Reston virus, has killed animals but not humans in the cases that have presented in China and the Philippines. The current outbreak is the Zaire strain.

How does the current epidemic compare?

It is estimated that there were 1,503 Ebola-related deaths between 1976 and 2008.

Ebola was first recorded in two simultaneous outbreaks in Zaire (now DRC) and Sudan, in which 602 people were infected and 431 died.

There was another significant outbreak in DRC in 1995, another in Uganda in 2000, in Congo in 2003 and again in DRC and Uganda in 2007, as well as smaller outbreaks in which less than 100 people were infected.

No single outbreak has had more than 425 people infected, making this the worst Ebola epidemic ever recorded.

This is largely because it has spread to cities, where it is harder to control. Previous outbreaks have been confined to rural areas.

The current outbreak is also untypical as there have been relatively few incidences of the virus in West Africa.

Fearful obstacles

The most effective way to control it is by following isolation protocol. But the success of these protocols can often be hampered by traditional beliefs, superstition and lack of trust in medical professionals – and in medical care. One woman, who was the first recorded case in Freetown, Sierra Leone's capital, was forcibly removed from hospital by her family.

It's easy to see that a disease with such poor survival rates creates fear in communities that could also lead to a reluctance to come forward when the symptoms appear, exacerbating the problem.

And medical staff are fearful too. "Some medical personnel are abandoning their duty stations for fear of contracting the disease," says Gadiru Bassie, working with Evangelical Fellowship Sierra Leone (EFSL) in Freetown – a Tearfund partner trying to control the spread of Ebola through community education.

"Others are scared of physical attack from communities that continue to cast blame on them for the outbreak," he says. Because most of those who are taken into an isolated clinic are likely to die from the disease, medical practitioners are sometimes conflated with the disease itself.

The virus can be killed by washing with soap and water, however Bassie says there is scepticism that this is just political hype. People don't believe that the chlorine, soap and hand sanitizers that are being distributed will work to tackle this daunting epidemic. Some are also not used to regular hand washing, and the lack of basic sanitation makes it easier for the disease to spread.

Another obstacle is a sense of defeatism, or a belief that the outbreak is a form of judgement from God – both of which make people reluctant to combat it.

One plane ride from Ebola in the UK?

The fact that Patrick Sawyer was due to travel to the US when he became ill has led to calculations about all the countries that might be one flight away from infection.

But it is highly unlikely that a major outbreak would occur in a developed country, because the medical resources available and infection control procedures would limit its spread.

There has never yet been a case of Ebola imported to the UK, and so far the World Health Organisation has not advised travel restrictions to affected countries.

Philip Hammond, the foreign secretary, hosted a meeting of the Government's Cobra emergency planning committee on Wednesday to discuss how to prevent it spreading to the UK.

Passengers suspected of having Ebola will be prevented from boarding flights to Britain. If a traveller is found ill on arrival in the UK, they will be taken to quarantine units.

British doctors have been told to look out for symptoms among those who have recently travelled to affected areas.

"We are very confident that we have very good people in the NHS, very experienced people who will be ready to deal with anything, if it were to arrive in the UK," Hammond said.

Similarly reassuring sentiments have been uttered by the French health minister Marisol Touraine, who said: "At the moment, the risk of the virus coming to Europe or to France is low. We are taking steps so that our country won't be affected."

Liberia, Guinea, Togo and Nigeria are now screening passengers. South Africa has started using thermal screening at the country's largest airport, near Johannesburg, to detect those with a fever and who might have Ebola.

The highest risk of infection is for medical staff caring for infected patients. Non-essential staff working for the US Peace Corps have been evacuated from the three affected countries, the Wall Street Journal reported today.

Christian charities Serving in Mission and Samaritan's Purse are among those evacuating non-medical personnel, spouses and children, after two aid workers working at a Samaritan's Purse clinic were infected.