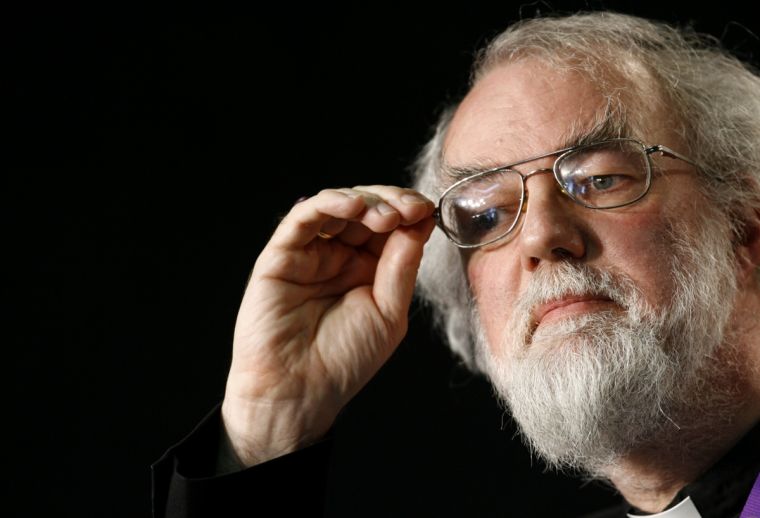

Rowan Williams: Repentance is appropriate after sins of the Protestant Reformation

The former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams has said that 'repentance' is an 'appropriate' way of looking back on the Protestant Reformation, the 500th anniversary of which is celebrated today.

In a wide-ranging interview he said it was 'impossible' to say whether Britain was a Christian country and admitted having an established Church of England reflected an 'odd' view of church and state.

Speaking to BBC Radio 4's Today programme about the legacy of Martin Luther for church and society today, he said: 'Looking back at the Reformation now, a lot of Protestants say, "there were things that we did to make it worse".'

He told interviewer Sarah Montague: 'We all need to look back at that history and say, "how did we end up executing one another, massacring one another?" It happened on both sides, and so repentance is a very appropriate way of looking back at that.'

Williams said it was 'impossible' to answer whether Britain was a 'Christian country' today, as although the nation was built on certain religious symbols and language, 'we're not a nation of practising Christians', and religiosity is simply perceived as 'weird' by many today. But, he said, a persistent interest in church remains and 'we're not quite as secular as we think'.

Asked if it was time for the CofE to be disestablished, he said: 'I've often thought of the establishment of Church of England: "I wouldn't start from here". It reflects a rather odd 16th century view of the absolute inseparability of the church and the state, which is realistically not where we are now.

'But I guess at the same time I'm a bit reluctant to think of disestablishing the church at this particular point, simply because it would feel like a concession to public secularism, pushing religious voices out of debate...it's not as if the church has huge legal privileges or power any longer, but it's there as part of a contribution to public debate which I think is quite important, as with other religious communities.'

He also suggested that the seismic schism which followed Martin Luther's rebellion could have been avoided with a more conciliatory approach, and less of a 'zero-sum game' attitude from both Catholics and Protestants. Such dialogue could have led to the Protestant Church of England, which Williams once led, never being established.

'I'd like to think it might have been possible for a Pope of a rather different colouring [responding to Luther] to say "you know the man's got a point, let's work on this, let's see what can be changed in church that avoids these obvious corruptions."'

Summarising what Luther's revolution was about, Williams said: 'What really exercises Luther...was the idea that the Church had simply failed to be itself. It had become another political organisation, a self-serving political organisation, the language of piety and devotion was being conscripted into fundraising and maintaining a particular structure, and Luther's personal passion was to cut through all that.

'He didn't think that he was starting a new church, he really didn't, he thought he was scrubbing the grime off what existed, but of course as soon as he raised that question, the issue of authority came up. Because who has the right to say the Church is corrupt?'