In the 19th century, the rector of St Mary and St Ethelburga in Lyminge, a small village in Kent, started digging in his churchyard looking for the tomb of Queen Ethelburga, the second wife of King Edwin and one of the most important figures in the early spread of Christianity across England.

It was already known from the historical records that Ethelburga established a monastery in Lyminge in 633AD, but the building had disappeared with the passage of time.

Curious, the rector dug down in his churchyard and discovered the walls of an Anglo-Saxon church alongside the Norman church still standing on the site today, but his findings were poorly recorded, leading archaeologists to once again re-visit the site over the summer.

What they uncovered is shedding new light not only on Ethelburga and her 7th century church, but how the foundation that was laid for the early progression of Christianity in Britain from a fledgling foreign faith in a pagan land, to a religion closely bound up with royal and political power.

Rob Baldwin, a member of the PCC, talked to Christian Today about the significance of the excavation and the church's plans to preserve its remarkable heritage.

CT: What brought about this dig? Where did it all start?

Rob: We've had over a decade of excavations across the village of Lyminge, not only the church, since 2008. Some remarkable things have been found, including evidence of settlement at around the end of the 5th century and a royal hall complex with some very large feasting halls, including a rather elaborate one with a concrete floor. There are only two sites in England that have been found with a concrete floor from this period and one of them is in Lyminge, so there is some remarkable survival in the archaeology.

Significant to early Christianity on these shores, we have the edge of a monastic enclosure that seems to be run from the end of the 7th century through to the mid 9th so there is a sequence of occupation in Lyminge that is one of the best in the country for this period.

CT: Tell me more about what was uncovered by Robert Charles Jenkins, the 19th century church rector and antiquarian who first excavated the site.

Rob: He found some walls immediately to the south of the church under the path and then paths at another point in the churchyard, and so because the first charter relating to Lyminge described the church as a basilica, what he thought he had discovered was a very large and grand, elaborate church.

This was one of the questions that has existed ever since that time. Do we really have a church that big here? Because there would be no other parallel for it in England.

We know that the Anglo-Saxon church was left uncovered until 1929, at which time it was covered over again because of deterioration caused by weather damage. That was 90 years ago and we didn't know what the condition of it was now. So we had reasons for wanting to look at it again. We wanted to answer some of these questions and see what the condition of it was. That was the justification for Historic England agreeing to the site being uncovered again.

Simply doing an archaeological excavation, though, wasn't going to be possible on its own because it would cause significant disruption to the churchyard due to its location. So what we decided to do was to use the excavation as an opportunity to renew the church paths, specifically to create disabled access to the church. We have a Norman church and the main entrance to the church is down steps which is really inconvenient so as a result of the dig, we were able to lay new paths to another door that could give level access into the church. That made this a much bigger project but at the same time one that was more capable of attracting the kind of funding that we needed, while also benefitting the church in other ways.

In a similar vein, we have developed a community engagement programme which is just getting off the ground now. The plan is to host a lot of activities that the community can get involved with such as artists in residence create unique artwork around the excavation and the development of the Royal Saxon Way pilgrimage route that people can follow.

The Royal Saxon Way is a 36 mile route across the grain of the North Downs from Folkestone to Minster-in-Thanet via Lyminge, linking 16 historic parish churches, many with Anglo-Saxon origins, and celebrating the powerful Anglo-Saxon royal women.

Uniquely, there are relics of the original saints at either end: St Eanswythe (Ethelburga's niece) at Folkestone and St Mildrith (Ethelburga's great great niece) at Minster. We launched it at the end of August with a walk along the whole route, led on the first day by Darren Miller, Archdeacon of Ashford who himself is a keen walker.

CT: Is there a basilica as Jenkins thought or is it a more modest building?

Rob: It's much smaller, essentially a two-cell building comprising a nave and chancel with an apsidal - or curved - end. The total dimensions only measure 13.4m long - that's the chancel - by 5.4m - the nave. So it's really very small. It's got a triple arcade dividing the chancel from the nave and there are piers in the middle that supported columns. These are interesting because we've got a fragment of one of those columns which is stone from Marquise near Boulogne.

CT: So the make-up of the structure is quite international then?

Rob: Yes it is. The nice thing about that is that there are a couple of other similar churches from the mid 7th century in Kent. There's St Pancras, in Canterbury, and St Mary's at Reculver, which was tragically demolished in the 19th century. But the columns, which were preserved and are now in Canterbury Cathedral crypt, were made of the same imported Marquise stone and they are 17ft high. What that suggests it that our church in Lyminge is probably about 8m high, so it's very narrow but proportionally speaking, very tall. That's something we now know about the structure because the excavation this summer was able to reveal its exact dimensions for the first time.

What we have found so far is typical of churches discovered from this period but we only have a tiny handful of them - the ones I've mentioned already and a few others, such as at Rochester, which is only the foundations, and another at Bradwell in Essex. The number of stone churches dating back to the 7th century that we've discovered are in the single figures.

CT: So it's definitely one of the oldest stone churches in the country, we just can't say it's the oldest stone church?

Rob: Yes, it's one of the oldest but we haven't got any absolute dating for it. All we've got are the foundations and there's nothing yet that's come out of the foundations that would allow us to date this.

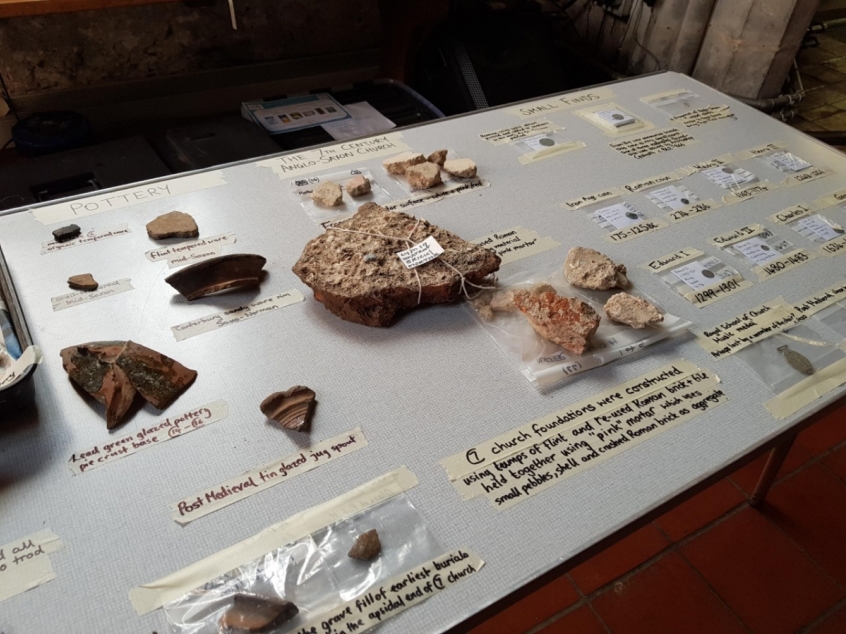

The stonemasons who built this church would have come from the Kingdom of the Franks and another interesting thing is that the mortar is a distinctive pink colour that comes from the crushed Roman brick in it. When we look at the other churches from this period, the Lyminge church looks almost identical on stylistic grounds.

There is at least one church that was being used in Canterbury at that time, St Martin's, probably an old Roman building, that was named in Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English people, and so can claim to be the oldest continuously used church in the country.

But because we believe it was a re-purposed Roman building, it differs from our site because it wasn't built at that time from scratch. The church in Lyminge does appear to be built from scratch.

We do have some unstratified pottery that is certainly 7th century, it might even be mid 7th century, so we can say there's activity going on around that date but we can't say that this pottery definitely relates to the church. In order to put an exact date on the church, we have to look at historical records with all the problems that go with that. There aren't that many and the question is: how reliable are they? But you can nonetheless put together a credible story.

CT: So what do we know about the story of this church?

Rob: The arrival of St Augustine in 597 marks the beginning of the Roman Christian mission to Britain. Ethelbert is King of Kent and welcomes Augustine to his kingdom and with that we see the creation of the first churches.

Ethelbert is the father of Ethelburga and she marries the King of Northumbria on the condition that he becomes a Christian. This was all part of the diplomatic offensive spearheaded from Kent to convert the Northumbrian kingdom.

After they are married, Edwin converts on Easter Sunday 627 in a wooden church in York and so begins the conversion of the north to Christianity. Unfortunately, though, Edwin is killed in battle in 633 and Ethelburga flees back to Kent.

There is a contemporary historical record that her brother, King Eadbald, gives her his estate at Lyminge. The earliest version of this record is about 100 years after the event but it is still 8th century. So there is evidence in the historical records that she came to Lyminge.

We know from other archaeology that has taken place around Lyminge that there was a royal estate here with large feasting halls. With this kind of royal status, it's an obvious place for her to have come to live. But as a Christian, she would have needed a church and it was appropriate for them by this period to be built in stone.

For example, the church that Edwin was baptised in was originally erected in wood, but after his baptism, a new one was built in its place made out of stone. The significance of this is that the proper material to build the churches becomes stone.

There is an argument therefore that if Ethelburga came to Lyminge and knew that she was coming for the long term, she would have built a church and built it in stone. The historical narrative is coming together with the archaeology. We've got an early church and who could have built it? It makes sense for Ethelburga to have built it.

One of the interesting things about the church is that on the north side there is a side chapel - known as a porticus - which is typical of the churches of this date. One of the purposes of these side chapels was to take a burial; they are mortuary chapels if you like.

This structure is actually built of the same fabric as the rest of the church so we know from this that it was all built at the same time. So we could see this as the mortuary chapel that was built for Ethelburga by Ethelburga in her lifetime.

CT: That's very significant, isn't it?

Rob: Yes. We think it's the mortuary chapel because there is a description of her tomb that was written in the 1090s when the Archbishop of Canterbury took her relics from Lyminge and there is a description that actually fits the porticus we have found in the excavation of the Anglo-Saxon church. We can't say for certain but there's a good presumption that's where it was.

CT: You have found skeletons too, haven't you?

Rob: Yes, but not in that porticus. We did find burials all over the site as it is a churchyard and in the middle of the Anglo Saxon church, we could see that Jenkins in his excavation actually followed the walls around and didn't disturb the middle of the chancel. This he left undug and so we found this island of untouched archaeology in the middle of the church.

We thought there was a chance that there could be some Anglo Saxon burials in the church so we decided to dig down. We took out eight burials in the end, all one on top of the other in a very small space but the lowest burial had 13th century pottery in it so they are much later.

These burials in the church were almost certainly made after the building had been demolished. These are people living in the village who are using the space where the church was but probably only after the church had been already demolished and passed out of memory.

CT: Was it still a significant place, a place of pilgrimage perhaps?

Rob: By that time no, because the relics had already been removed. We do know that it was a place of pilgrimage into the early 11th century because there was a hagiography written of St Eadburg, who was Abbess at the Minster in Thanet until her death in 751. At the end of the 8th century, so about 50 years after she died, Minster and Lyminge were actually ruled by the same Abbess, a bit like a joint abbey. It looks like that is the context of the relics being translated from Minster where she died to Lyminge and we know from a charter that Eadburg was in Lyminge by 804.

In those days, they moved relics to promote the cult of the saint and it looks like that's what was going on here. The hagiography written 200 years later says that she was the Abbess and it relays the miracles associated with her shrine and holy well at Lyminge. This manuscript has only been found relatively recently and is being published later this year, so it's actually a new manuscript in terms of what we know about her and it's a nice bit of the Lyminge story.

CT: Is it too early to say what this dig might have changed in terms of our understanding of early Christianity in England? Has it offered any new revelations or is it more about confirming what we thought we knew?

Rob: What we have in Lyminge, within the context of all the other archaeology we have found here, is a centre of power, the first centre royal power. And this then becomes ecclesiastical power through the Anglo Saxon period. It later becomes one of the manors of the archbishops and we actually found a medieval residence of an archbishop in the churchyard as well.

What we can see in Lyminge that perhaps you can't see in other sites is the way that the site has evolved. What Lyminge is doing is showing how the royal family in Kent used the site to protect their interests. They were using abbeys - something that has been explored by John Blair in his book, The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society - to perform a political role in protecting the interests of the royal family and the kingdom in this fight between good and evil.

In this period, there was a perception that you had this temporal conflict going on but also a spiritual conflict. You would have the men defending the interests of the kingdom on the battlefield and women defending these interests through their prayers. That's why there was this mushrooming of abbeys and in the later 7th century we see all the kingdoms become Christian.

The conversion of England was really quick; it was within the space of a few decades within the 7th century. This isn't hard missionary work; this is a political thing. But they then consolidated it because they felt that the reason they'd converted was because it was to their interest. And so they were investing heavily in these monasteries and abbeys and that's what you can see happening in Lyminge.

But what's different here is that we can actually see it; the archaeology has been found, whereas at other sites it's so partial, it's largely in records. Lyminge is so special because it demonstrates this continuity from how things began.

CT: What do you think this site says about Ethelburga as a woman? Would this church being erected by her have been interpreted as a big statement at the time?

Rob: I think it would have been. You have her building a masonry building for one thing. There were ruined Roman masonry buildings at this time but not many people were putting up new ones in this period. So just the fact that she was doing that was quite a statement in itself. She would have had to bring in masons and the stone to do it and that's also quite a big thing.

I think what she's doing is stamping her mark on the estate. She's saying: this is the right way to do it, this is what I'm going to do. And this was breaking the mould because there weren't many stone churches around to copy. So she was really groundbreaking in a way and asserting herself; she wasn't being meek and saying, ok, I've just been retired to this nunnery and I'm just going to get on with it quietly. She was asserting herself and we see this in later charters. The abbesses of the royal abbeys were signing charters alongside the men.

CT: So some of the Christian women of the Anglo-Saxon period were really quite powerful?

Rob: Yes, they're powerful, feisty women. I think we forget this because we think it was a male society. But no, in this early period, women had a really significant role. If you want to answer the question of what this is telling us, it's reminding us that things were different.

Right through the 7th, 8th and even into the 9th century, women had a recognised political role. It was different from the men but it was still important.

CT: It's interesting that in some ways, when we look at what's going on at this time period in the churches, it seems like the precedent is being set for church and political power becoming very intertwined down through English history.

Rob: Yes, I think that's a fair observation and we see that this does continue.

CT: In terms of the dig, what's next?

Rob: The dig itself is finished and the site is going to be backfilled in the next week. It's with the University of Reading for analysis and we will produce an academic report. Our first publication, an edited version of the blog we run around the dig over the summer, is already in the press right this moment.

But it was an important part of the project to create something accessible and that's what we're doing. We'll be producing a trail around the village with info panels so that visitors can go around and look at the sites. Of course, there's no archaeology visible above ground but there will be reconstructed drawings and we have also done a 3D laser scan of giving a much more detailed picture of the church. We are working with the University of York's Centre for Christianity and Culture to produce a sequence of 3D images showing the evolution of the site. We'll need to do more fundraising, though, to bring that project to life.