Last month the Islamist militant group known as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) announced a rebrand, and changed its name to the Islamic State (IS).

It was just the latest in a number of shape-shifting reinventions as the organisation that started life as a small band of extremist Sunnis in Iraq in 1999, has come to dominate large parts of Iraq and persecute its people.

The violence against Christians in the region has escalated in recent weeks – as has violence against everyone in Iraq who doesn't follow IS's extreme Sunni practices.

Known as 'Al-Qaeda in Iraq' since 2004, the group was one of a number of extremist groups that emerged to fill the power vacuum in Iraq when Saddam Hussein was toppled in 2003.

No longer a minor al-Qaeda offshoot, it now has the strength to rival the formerly unstoppable force of global terrorism.

"They are confident they can use their momentum to see how much support the can get – how much they can persuade others to join their cause," says Shashank Joshi, senior research fellow at the Royal United Service Institute.

Al-Qaeda banished IS in February this year when IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi rebelled against Ayman al-Zawahiri, Bin Laden's replacement as leader of al-Qaeda.

Unlike al-Qaeda, which focusses on the foreign (usually meaning western) enemy, IS has concentrated on acquiring physical territory, embodying a different understanding of global jihad.

Sheltering in Pakistan, the core al-Qaeda group has been relatively passive in recent years. IS has been anything but.

"Al-Baghdadi is saying 'We've got territory, we have oil, a system of justice, we impose taxes, we are a state – and the jihad starts at home'," Joshi says.

Al-Baghdadi's strongly interventionist approach acts as a rallying cry to other extremist Sunnis, who feel under-represented by Baghdad's Shia-majority government.

Invading vulnerable, war-torn cities in Syria, including Raqqa, was a prelude to what has since happened in Iraq. Syria served as a good base from which to move into central Iraqi cities, such as Ramadi and Fallujah.

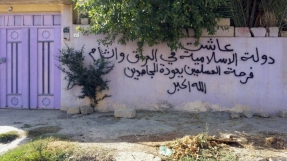

The 'convert, pay tax, leave or die' ultimatum IS offered Mosul's Christians last weekend was a technique first put to the test in Raqqa. In February, Syrian Christians were told they had to pay a certain amount of gold for every adult male in return for their lives.

Now the land that the prophet Jonah reluctantly brought back to the Lord is almost entirely emptied of its Christian population, as they have been forced into exile along with those fleeing Syria.

But you could say the horrific attacks on Christians are moderate in comparison with the indiscriminate killing of Shia Muslims in Iraq, particularly in Anbar province.

"If you look at who ISIS hates, there is more hate reserved or those who are heretics rather than people of the book. There's a special venom reserved for Shias – they're seen as heterodox, heretical, evil," says Joshi.

Iraq is one of the few countries that has a large Shia representation – worldwide they make up only 10-15% of the Muslim population. The Pew Research Center estimated that the Shia population made up 51% of Iraq in 2011, which is still less than the 90% in Iran.

But while Shias are in the minority in certain parts of northern Iraq, they belong to a powerful majority in Baghdad, where IS has so far not succeeded in taking ground. There are thought to be underground IS cells in Baghdad waiting for the right moment, but only time will tell whether the rumours prove true.

Motivating IS in Iraq is a complex combination of a particular form of jihadi philosophy, sectarian division and a response to western intervention in the past. The result has been bloodshed on a scale likened to the religious equivalent of ethnic cleansing.

In June the Iraqi government called on the international community to intervene. Not unsurprisngly, the response was cautious.

Over the past couple of years IS has gone from being relatively unknown, to a household name, and is now the richest terrorist group in the world. You could argue that being shot at by American forces would be the ultimate flattery – a sign that IS is now a major player in the global terror stakes.

But surely we don't need missiles raining on Mosul before we recognise the risk posed to Christians and to all those persecuted by this growing terror force. As Christians we are connected to those suffering in Iraq, by both religious and political history, for better and worse.