The response of some – by no means all – white evangelicals to the events in Charlottesville has been curiously tone-deaf. None of them approves of white supremacists, but there's been an attempt to draw equivalences between that and the opposing far-left fringe that has compromised some of their critical statements.

Evangelicalism in the US has always been on the front line of debates about race, because of its strength in the South – and sometimes it has been on the wrong side of that line. But one of the world's greatest evangelists showed how it was possible to overcome the prejudices and assumptions of early upbringing.

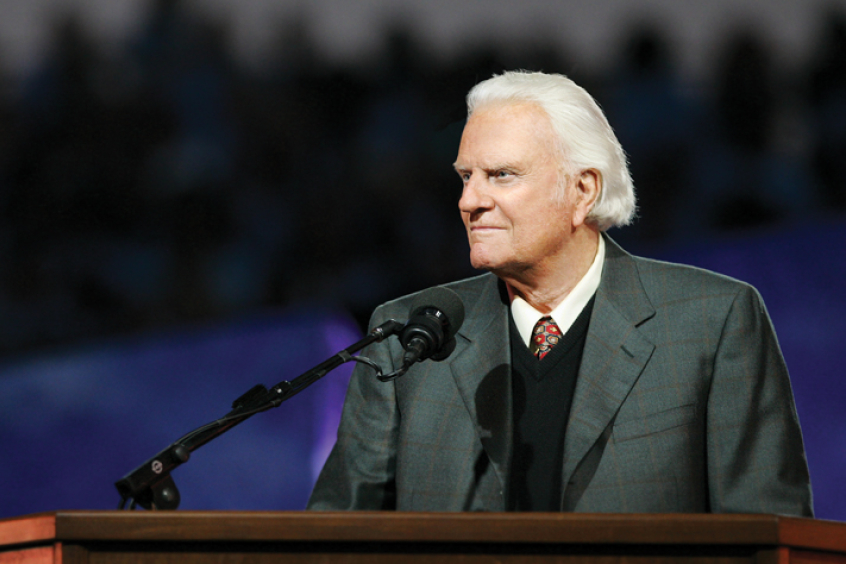

Billy Graham's record in opposing racism, at a time when it was far more blatant, is a shining example to follow.

In Grant Wacker's biography, America's Pastor, he writes about Graham's Civil Rights record. As a Southerner, he initially took segregation for granted. But by 1956 he had become a convinced anti-segregationist. He wrote articles denouncing racism as sin – a major step. In 1957 he invited Howard Jones, an African American evangelist, to join his team; Jones accepted, though later recalled that when he first sat on the platform with white participants the seats on either side of him were unoccupied. Graham also used black singers, including Mahalia Jackson at Ethel Waters, at his rallies.

Nevertheless, he wasn't an out-and-out civil rights campaigner, serving as an ally at one remove – for Graham, it was all about whether a cause advanced the gospel, and he was reluctant to get drawn too deeply into any other project.

He wrote a influential article article for the Reader's Digest in 1960 deploring segregation in church and quoting Martin Luther King – but urged King to 'put the brakes on' a little after a demonstration. They clashed over the Vietnam War, but he was to describe King's assassination as 'one of the greatest tragedies of American history'.

During the 1970s his stance became even clearer as his thinking developed. He preached to the first major mixed-race meeting ever in South Africa. He said in Moscow that he had undergone three conversions in his life: to Jesus Christ, to racial justice and to nuclear disarmament.

In his extensive analysis, Wacker admits Graham did not always speak as clearly as he might and should have done. However, he says: 'Though he was not always as forthright as he might have been, even by the standards of his time and place, he made it difficult for millions of people publically to resist racial justice and still call themselves Christian. Graham took that option off the table.'

Wacker illustrates moments at which Graham's influence was key. President Eisenhower and Vice-President Nixon phoned him before sending troops into Little Rock, Arkansas to enforce integration and Graham told them they had no choice. His words were leaked to the press and Eisenhower had the support he wanted.

Another example also comes from Little Rock, where Graham held an integrated crusade in spite of fierce opposition from the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens' Council, which distributed 40,000 flyers opposing it. One of those in the audience was a 13-year-old boy named Bill Clinton.

And Wacker's third example is his acceptance of a joint invitation from white and black ministers' meetings in Dothan to hold a crusade there. He cancelled a European tour to accept and the event was the first integrated public meeting in the city's history.

Wacker concludes that 'when it came to civil rights...he confronted his friends more often than his enemies. That stance took a special kind of courage too. We do not have to rank forms of courage in order to acknowledge the price paid and the good accomplished.'

The furore over Charlottesville has shown that however far America has come in dealing with its racial past and present, there's still a long way to go. Evangelicals are still deeply involved in the conversation – though they are not always saying the right things in the right way.