Anglicans seeking a faculty from their diocese to replace the pews or move the font sometimes groan at the levels of bureaucracy they have to battle through to get anything done. Multiply this a thousand-fold to get some idea of how Jerusalem's Church of the Holy Sepulchre functions and what an extraordinary agreement has just been reached.

Work is to start on repairing the shrine at the heart of the complex, called the Aedicule, in which is supposedly located the tomb of Jesus. The renovation will cost $3.4 million and will see the monument, which in its present form dates back to 1810, completely rebuilt. The marble slabs will be taken off, the 12th century Crusader shrine beneath will be repaired and the cracks in the rock-hewn tomb under that, where many Christians believe Christ was actually buried, will be filled. The Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches will each pay a third of the cost.

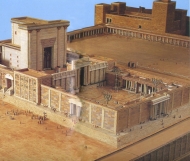

But while the renovation is technically challenging, a far greater challenge was getting agreement over the need for the work. Responsibility for the Holy Sepulchre is divided between six Churches – the other three are the Coptic, Ethiopian and Syriac Orthodox – each of which jealously guards the privileges and territory granted to it by the Ottoman rulers in 1853. Any infringement of these is bitterly resented and the 'Status Quo' established then is rigidly enforced.

In 1995 the six denominations finally came to an agreement on painting a section of the central dome. It had taken them 17 years of debate and illustrates just why the building is in such a state.

Just how far the monks and priests are prepared to go is illustrated by a ladder. It is an ordinary ladder made of cedar wood and propped up against one of the exterior windows of the church. It has been there since at least 1757, because the various Churches all need to agree whose responsibility it is to move it and they haven't been able to do so. (In 1964 Pope Paul VI said it would have to stay there until the Catholic and Orthodox Churches reconciled.)

A ladder is one thing, but there are arguments and fist fights too. The Ethiopians and Copts – poorer and less influential than they were – have space on the roof of the church. One section is disputed; during Easter prayers in 1970, Coptic monks briefly left their rooftop monastery, which allowed the Ethiopian monks to change the locks and take it for their own. Since then a Coptic monk has sat on a chair there all the time to stake his church's claim. On a hot summer day in 2002 he moved his chair a few centimetres into the shade; this was interpreted as an act of aggression and the fight that followed saw 11 monks hospitalised.

On another occasion, in 2004, a door to the Franciscan chapel was left open during the Orthodox celebrations of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. This was taken as a sign of disrespect by the Orthodox and a fistfight broke out.

On Palm Sunday in 2008 a brawl broke out when a Greek monk was ejected from the building by a rival faction. In November of the same year 2008, a clash erupted between Armenian and Greek monks during celebrations for the supposed 4th-century discovery of the cross on which Christ was crucified. The Armenians found their path blocked by a Greek Orthodox monk posted in the tomb. The whole thing was filmed and put on YouTube.

It's perhaps just as well that the keys to the church are held by two Muslim families, who have held their ancestral positions since 1192. There is, at least, no chance of a lockout.