In September last year the Centers for Disease Control depicted a worst case scenario in which the number of people infected with Ebola could reach 1.5 million by January 2015 without swift intervention, and the UN called for $1 billion to tackle the epidemic.

Governments and aid agencies did respond, and the swell of humanitarian assistance has helped to contain its spread. In the week up to 18 January the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported a combined total of 145 new confirmed cases in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, the three countries most affected in the current outbreak. The Liberian government said late last week that there were now only five confirmed cases in the country, in comparison with the 300 new cases per week recorded in August and September.

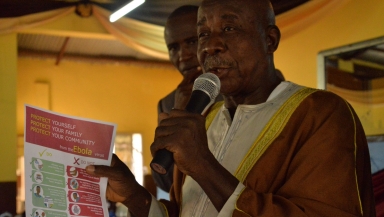

It has been an uphill battle to educate communities and overcome the various stigmas around sanitation and hospitals, but it appears to be paying off. Of course, before the virus is entirely eradicated, governments in the affected countries will be rightly fearful of complacency.

"People are very encouraged to see the numbers of new cases going down, but they also recognise that the battle will not have been won until there have been zero cases in all the provinces for at least 42 days," said Sarah Wilson, Ebola response communications manager for World Vision.

"So far only two provinces have had zero cases for that length of time. It only took one case to start the outbreak. So I don't think people will relax for some time yet," said Wilson, who has been based in Sierra Leone for the past two months.

This is not a virus to underestimate. This outbreak has been the worst on record by a significant margin, with the WHO reporting more than 21,000 confirmed, probable and suspected cases in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and more than 8,600 deaths, though actual figures could be higher.

Outbreaks such as this don't just affect the nation's health. For every person who died, there will be repercussions – economic and social impacts on families, communities and nations.

There are now four major challenges facing the world as the focus shifts from fire-fighting to planning for the future.

Challenge 1. Infrastructure – The world is 'dangerously unprepared'

The epidemic has exposed once again the fragile, underdeveloped infrastructure in the three main countries affected, all of which are among the poorest in the world.

Liberia had only around 50 trained doctors for its 4 million population. Sierra Leone found it was radically short of hospital beds. In October, more than 1,100 beds were needed for Ebola patients and there were only 304 available for the country of 6 million people. There was also shortage of ambulances, and the fuel to run them.

The WHO has also admitted that the response to Ebola was too slow. But this doesn't mean that it won't happen again. Dr Jim Yong Kim, president of the World Bank Group said this week that the world, not just Africa, is "dangerously unprepared" for future pandemics like Ebola.

Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the WHO, also said that "Ebola preyed on the fear of the unfamiliar.

"The disease was unexpected and unfamiliar to everyone, from clinicians and laboratory staff to governments and their citizens," she said.

One encouraging sign, however, is that the grave concerns about Ebola spreading across Africa, and even the world, have not been realised. There have been some cases in Nigeria, Mali and Senegal, but it has not been widespread, and it is generally thought that the virus was effectively controlled.

Challenge 2. Economy – Africa is not a country

Although fears that the whole region would be hit economically have been assuaged, the three main countries affected face huge economic challenges.

In Liberia, almost half of household heads are unemployed, according to a recent World Bank report. And in Sierra Leone many small household enterprises have gone out of business or suffered a substantial reduction in trade.

Sierra Leone was expected to see substantial economic growth in 2015 of 5-10 per cent, and instead its economy is shrinking, with Guinea heading in a similar direction. Although the Liberian economy is expected to grow this year, it is thought it will be at half the rate that it was before the outbreak.

Investment plans were put on hold, and tourism declined. Public activities were reduced in an attempt to control the disease. Markets closed, and street vendors lost their source of income, and in Liberia non-essential government workers were sent home.

According to The Economist, by November last year tour operators across Africa reported the biggest drop in business in living memory. This is partly owed to the fact that some think of Africa as a nation, not a continent, and was described by one travel agent as "an epidemic of ignorance".

With headlines about the fear of Ebola spreading globally as a result of air travel, it's easy to see how anxieties emerge. David Evans, a senior economist at the World Bank, said: "The vast majority of the economic impact of this crisis has been fear."

But if the fear hadn't been there, would the response to Ebola have been so strong?

This week Oxfam called for a form of post-Ebola 'Marshall Plan' to prevent countries recovering from the virus from being hit by economic disaster.

On a visit to Liberia, Oxfam GB's chief executive Mark Goldring said: "People need cash in their hands now, they need good jobs to feed their families in the near future and decent health, education and other essential services. They've gone through hell, they cannot be left high and dry.

"The world cannot walk away now that, thankfully, cases of this deadly disease are dropping. Failure to help these countries after surviving Ebola will condemn them to a double-disaster. The world was late in waking up to the Ebola crisis, there can be no excuses for not helping to put these economies and lives back together."

Challenge 3. Family and Society – Back to school but not back to normal

Schools in Liberia and Sierra Leone are due to open again in February, having been closed for months in an attempt to reduce interpersonal contact.

But things won't necessarily return to normal. VICE News reports that a number of private Christian schools in Liberia, which are often thought to have a higher standard of education, may be forced to close as a result of the economic downturn.

Many children have been emotionally traumatised by the outbreak – those who caught the virus will have experienced the fear and stigma associated with it, as well as the loneliness of quarantine, others have been orphaned. In recognition of the emotional trauma that people face, World Vision is training people in psychological first aid.

Christian development agency Tearfund reported the story of one Liberian woman, Josephine, whose husband and two children died from Ebola. She also contracted the virus and was admitted to a clinic, but recovered and has taken six orphaned children from the clinic into her care.

Stories of newly formed families are also paired with other, less comforting reports of people being rejected by family members or their communities after they have recovered over fears of the disease spreading.

Josephine said: "Since we returned from the Ebola Treatment Unit, it has not been easy for us to get food. Many people in the community that we were once close to are afraid of us." Tearfund's partner organisation, EQUIP, has been distributing food parcels to households across Liberia who have been quarantined and consequently struggling to get food.

One of the significant measures taken to control the virus was to change funeral practices, as the bodies of Ebola victims are still highly contagious after death. Although people were told to report the deaths, the bodies were disposed of without any opportunity for a ceremony. People were reluctant to call the teams, and so the protocol wasn't as effective as it might have been.

World Vision has been working on a government-funded project in Sierra Leone to ensure the dead are given safe and dignified burials. Teams are trained to come to the home of the deceased in protective clothing, and safely, but solemnly remove the body and clean the home. Families are able to invite a member of clergy, either Muslim or Christian, to perform a ceremony.

There have also been smaller societal changes, including in peoples' body language. "Sierra Leoneans are a very expressive people who like to hug and touch each other," said Wilson. "It is difficult to avoid doing that, but people have taken that messaging very seriously. People touch their hands to their hearts and bow as a greeting now...it seems awkward at first, but everyone does it."

Challenge 4. Health – Ebola, one among many

Many have made the comparison between Ebola and other diseases that have a crippling hold on a number of African nations, such as malaria and HIV. In 2013, 6.6 million people contracted malaria in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, and 20,000 people died from the disease. While it's difficult to argue that one disease is 'worse' than another, it is true that Ebola is one concern among many.

A WHO report in December showed that although malaria deaths have fallen in recent years around the world, Ebola poses a risk of resurgence. This is partly a result of the stretch on medical resources; some of the – already limited – health clinics in Liberia were shut down as they became places of infection instead of treatment. And this in turn may have made people more reluctant to attend outpatient clinics, which have also seen a fall in numbers attending.

The question over trial Ebola vaccines once again drew distinctions between The West and the Rest, with high-profile cases of Westerners being given experimental drugs, while the thousands in West Africa were not. But when the experimental drug ZMapp was sent out to Liberia in August it was seen as ethically questionable.

There has been huge pressure to fast-track developments of possible vaccines and treatments. In November, clinical trials began in Sierra Leone and Guinea using the blood of Ebola survivors to help victims. At the start of January Médecins Sans Frontières began a clinical trial for an anti-viral drug in Liberia, and last week British pharmaceuticals firm GlaxoSmithKline shipped its first trial vaccines to Liberia.

Jon Pender, a vice-president of GSK, said at an event in Parliament last week: "The reason we don't have a vaccine is because it wasn't a priority for anyone, and there are understandable reasons for that.... The number of people affected each year was very small and the overall disease burden, in comparison to other disease like malaria or HIV, is tiny.

"The fact is that in the 40 years that we have known about Ebola, including the present outbreak, there have been about 24,000 known cases. There are that many cases of malaria every hour."

But while a vaccine may one day eliminate the virus, it's clear that the same recurring faultiness of underdevelopment leave these countries – and particularly their economies – still vulnerable to attack. Ebola has proven to be a global challenge, though one that cost the poorest most, and international commitments are needed for the long haul, as much as ever as the death count falls.