How far can a theologian go wrong before we dismiss his whole body of work? It's a question that has been raised by a recent investigation into Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder's sexual abuse of women during the 1970s and 80s.

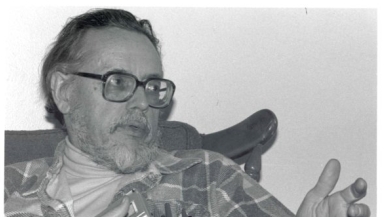

Yoder isn't just respected in the Mennonite tradition, he's regarded as a major figure in theological and philosophical ethics. The abuse was not a secret – it's been widely documented – but has nonetheless been overlooked for many years.

His most well known book, The Politics of Jesus, published in 1972, is considered a classic on Christian pacifism. But while he is remembered for his contribution to theology, he also hurt a large number of women through an 'experiment' in sexuality, which he based on a theological theory.

For the first time since Yoder's abuse came to light in the 1990s, the Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Indiana held a special service of 'lament, confession and commitment' on March 22 this year.

Yoder, who died in 1997, was a theology professor at the Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary from 1960 until his resignation in 1984. He was also president of Goshen Biblical Seminary for a three-year period during the 1970s and taught at the University of Notre Dame for 30 years. In 1994 the two Mennonite seminaries joined and were later named the Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS).

No legal charges were ever filed against Yoder, but mental health professionals who worked with him from 1992-95 have suggested that more than 100 women faced unwanted sexual violations. These advances range from sexual harassment in public places to – in rare cases – sexual intercourse.

His behaviour was known about by seminary leadership, and several attempts were made to deal with Yoder at a local, denominational and seminary-level during the 1980s and 90s, though none was particularly effective.

Some of Yoder's victims approached AMBS' current president Sara Wenger Shenk when she arrived at the seminary five years ago, The Elkhart Truth reports in an article republished by the National Catholic Reporter. Together with Ervin Stutzman, executive director of Mennonite Church USA, Shenk established a 'discernment group' to look into the church's response and to work towards reconciliation with the victims.

The group commissioned historian Rachel Waltner Goossen to investigate the abuse and the church's response. She was given access to previously unseen documents and interviewed 29 people, including some of Yoder's victims.

Goossen published a report on her findings in the January edition of the Mennonite Quarterly Review, and the seminary's service of repentance in March was one way of acknowledging the truth of the women's claims, and apologising for the institutional failures that took place.

Shenk said in a statement of confession and apology at the service that she initially had reservations about apologising on someone else's behalf.

"But today, by the authority given me by the AMBS Board of Directors, and I believe by the Holy Spirit, and by everything I know to be true about the Gospel, I name the violation of body, mind and spirit that happened on the watch of this seminary, as evil; and I renounce it," she said.

Addressing the victims, she added: "What was done to you, whether sinful acts of commission or omission, was grievously wrong. It should never have been allowed to happen. We failed you. We failed the church. We failed the Gospel of Jesus Christ."

Those who knew of his misdeeds kept them confidential. Marlin Miller, who was president of the seminary at the time, tried to reason with Yoder by theological debate for many years, but having failed to change his behaviour, Yoder was allowed to resign from his post at Goshen Biblical Seminary in 1984. When he informed Notre Dame, where he continued to work until his death, he said that there were 'delicate dimensions' to his decision.

The women he abused did speak out, but Yoder's reputation as a theologian and respected Mennonite leader seems to have been remarkably resilient.

In 1992 a denominational task force presented him with 13 charges of sexual abuse. His ministerial credentials were suspended and he was encouraged to have counselling. Yoder never denied the charges and complied with the disciplinary process.

"These charges indicate a long pattern of inappropriate sexual behaviour between you and a number of women," the task force told Yoder, according to Goossen's report.

"The settings for this conduct were in many places: conferences, classrooms, retreats, homes, apartments, offices, parking lots. We believe the stories we have heard, and recognize that they represent deep pain for the women. ... The stories represent ... a violation of the trust placed in you as a church leader."

Yoder gave his victims a limited, indirect apology. Carolyn Holderread Heggen, one of the eight women who pressed the church to respond in 1992, told the New York Times that he had issued a statement that said "he was sorry that we had misunderstood his intentions, as he never meant to hurt us."

Goossen said in her report: "Since Yoder's death more than a decade and a half ago, some admirers of his theology have offered various explanations for his behavior.

"But in keeping the focus on Yoder rather than on the consequences of his actions, these speculations deflect attention away from institutional complicity."

The service held at the seminary in March was part of two days of 'reunion, listening and confessing'. In her apology, Shenk gave some explanation of why Mennonite leaders had failed to confront the abuse effectively.

"We allowed ourselves to be held captive by intellectual argumentation and theological constructs that used biblical language to intimidate, and to justify sexual deviancy and immoral behaviour," Shenk said.

"Along with so many others, we fell prey to our desire for a hero. Enamoured by the brilliance that put our treasured peace theology on the world stage, we failed to truly listen to those whose bodies, minds and spirits were being crushed. There is no excuse."

Theologian Stanley Hauerwas, a great admirer of Yoder's work, wrote a parenthetical remark in one article that said: "The fact that he has submitted to his church's discipline process regarding sexual misconduct is but a testimony to his commitment to nonviolence as the community's form of behaviour."

Although his behaviour was publicised in the 1990s, it is still not that widely known. No mention was made of his more questionable theology in his obituary in the New York Times, for example. His reputation as a theologian has remained intact. He is frequently cited by contemporary theologians, church leaders and Christian thinkers.

Baptist minister and head of Oasis charity Steve Chalke's book, Being Human, which was published last week, has been criticised by one British blogger for referencing Yoder.

In an open letter that called on Chalke to retract and edit the book Thomas Creedy wrote: "at various points, Steve favourably quotes Yoder... And he does it without acknowledging that Yoder is accused of, nay, responsible for, some serious crimes. Crimes that, regardless of your views on a whole range of questions, go right to the heart of who we are and how we are 'Being Human'. Steve seems to quote and use Yoder's ideas without remotely referencing these crimes that have come to light."

The references to Yoder in Chalke's book are not direct quotations, but include a story about Yoder and his pacifism, and a footnote about an idea from The Politics of Jesus.

Creedy told Christian Today that it is the context of the book that makes the references to Yoder concerning.

"It's the fact that the book is trying to make space for inclusion and love and welcome. You have to love the people who didn't get voice, who don't have a voice.Yoder's voice lives on in books and essays – to be truly human we need to listen to the voices of those who are not heard," he said.

Creedy added that he was not against people reading Yoder's theology, but said they shouldn't do so "blithely".

Chalke told Christian Today that he didn't know about Yoder's personal history before referencing him in the book, but wasn't inclined to make any changes to the book in light of the information.

He said The Politics of Jesus had been a "massively influential" book in his life. "I think it's a fantastic piece of theology," he added – an opinion which would no doubt be shared by many.

He acknowledged that there was a "clear gap" between "who Yoder is revealed to be and what he espoused" but added "There's always a huge gap between our aspirations and behaviour."

He said there were numerous cases from history of leading theological figures who had morally questionable personal lives, pointing to the widespread influence of Karl Barth, despite his unconventional domestic arrangements (he lived with both his wife and his theological assistant Charlotte, to whom he declared his love in letters).

"King David was hardly sweetness and light," he added.

He said that although he appreciated Yoder's theology, it was not a defence of the allegations against him. "Just as I consider Karl Barth an extraordinary theologian... But it's his theology I'm reading, and I understand there's always be a gap between who we [say we] are and what we do."

However, Krish Kandiah, president of the London School of Theology, said that there are aspects of the reports about Yoder which make this different from a lapse of judgement or personal indiscretion. He said the scale of Yoder's abuse, that it was continual, and that he remained largely unrepentant, put him into a "different category".

"It's the fact that he's writing about ethics. You at least have to engage with it, you can't just ignore that part of his life," he said. "Imagine how it feels if you're a victim of sexual abuse and your abuser is still being used as a source of Christian ethics."

The Mennonite Church has at last begun to take this seriously. MennoMedia decided in 2013 to issue a statement at the beginning of all publications of Yoder by the Herald Press, which said: "At Herald Press we recognize the complex tensions involved in presenting work by someone who called Christians to reconciliation and yet used his position of power to abuse others. We believe that Yoder and those who write about his work deserve to be heard; we also believe readers should know that Yoder engaged in abusive behavior."

This issue inevitably raises wider questions about how we respond to theologians who are known to have a troubled past. Yoder is perhaps an exception, in that he is said to have abused women within the context of his work and used theological arguments to support his behaviour.

At the seminary's service of repentance, there was a clear acknowledgement that Yoder's profile as an eminent theologian had skewed the perception of and response to his abuse. It would seem that the same bias applies in some contexts today.