In 2016 Donald Trump attracted the support of 81 percent of US (mostly white) evangelicals. More recent polling has revealed that from May 2019 to March 2020, the number of weekly church-attending white Protestants convinced that Donald Trump was 'anointed by God to be president' grew from 29.6 percent to 49.5 percent. But where do they stand now, in the context of his response to Covid-19 and the racial unrest on US streets?

The 'chaos candidate' in a time of chaos

Trump has been described as a 'chaos candidate', who thrives in conditions of turbulence and polarization. However, 'the 'chaos candidate' has met a 'chaos event' in the Covid-19 pandemic, and in the unrest on the streets, that possesses the potential to lay bare the inadequacies of his presidency.

In late April-early May, polling by the Pew Research Center found that the share of white evangelicals who gave Trump positive marks for his handling of the Covid-19 crisis had fallen 6 percentage points compared with the second half of March. Nevertheless, three-quarters of these evangelicals still thought that Trump was doing an excellent (43 percent) or good (32 percent) job of responding to the pandemic.

At the same time, some commentators have suggested that a shift has occurred in Trump's relationship with evangelicals, suggesting that he now favours a number of proponents of the so-called 'prosperity gospel' (most notably televangelists such as Paula White and Guillermo Maldonado) over more mainstream evangelical leaders. Their considerable media presence may help explain this. It may also reflect increased radicalization on the part of Trump in this time of turbulence.

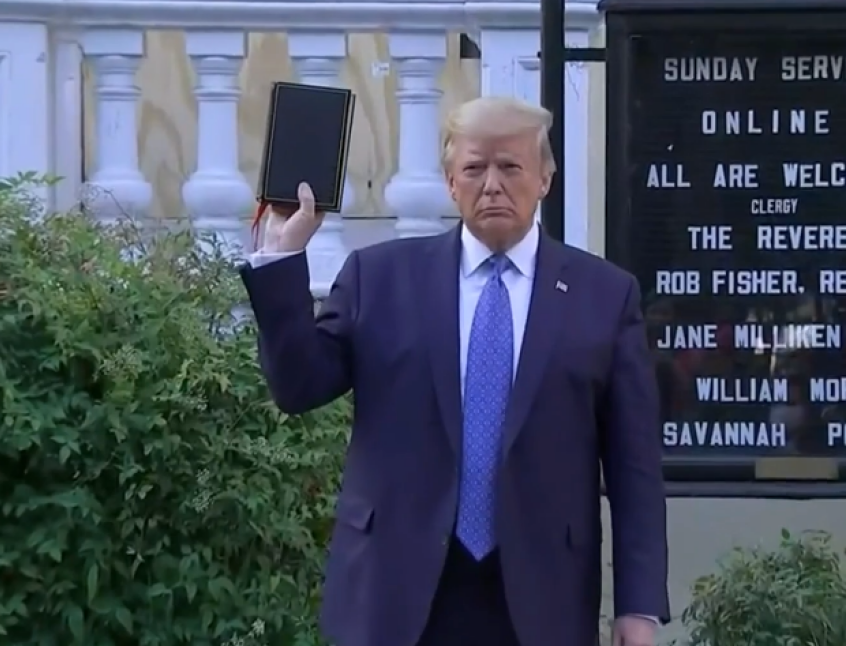

This may be correct, but a general appeal to his wider evangelical base clearly explains the Bible photo-opportunity at Washington's St John's Church on 1 June. Only minutes before this, Trump had threatened to unilaterally deploy the army on the streets of US cities. The conservative Christian vote was explicitly the target of the gesture. When one recalls that Florida, a key swing-state, is 70 percent Christian and 24 percent evangelical, and that in 2016 Trump won it by only 1.2 percent of the vote, one can see what was going on at the church.

Clearly, Trump has been determined to present the unrest in US cities as a law and order issue, rather than one revealing deep historic and structural racial problems in the nation. It may also have been prompted by his recognition that the vast majority of evangelicals who support him are white. His appeal to black evangelicals is low. This makes the pitch at the church all the more obvious and, to many, all the more alarming.

The question is: did Trump succeed in this pitch? Franklin Graham, on Facebook, asserted he was not offended by the events at the church. He was not alone, among leaders of the evangelical-right, to voice such sentiments, in the face of the widespread condemnation of Trump's action. Similar support was offered by Ralph Reed, who said, "I was glad that he went there," and described the action as "symbolic". It was certainly that. On 16 June, Robert Schenck – a self-described former ultra-conservative activist – condemned the action at the church as "profane" and expressed his distress at the continued widespread support for Trump among white evangelical leaders. He described this as evidence of a "moral collapse" among evangelicals, resulting from a "Faustian deal" made with Trump, in order to achieve their political and social goals.

However, the situation is complex. From the start of the Covid-19 pandemic to early June, and the unrest following the death of George Floyd, unease has occurred among some evangelicals. Recent polling by the Public Religion Research Institute revealed that between March (the start of the Covid-19 crisis) and the end of May (race-related unrest), Trump's approval rating among white evangelicals fell from nearly 80 percent to 62 percent.

Where does this leave 'the evangelical vote'?

This raises the question: when November's election occurs, how will evangelicals vote? The evidence from 2016 may be significant. As that year's presidential election approached, Trump's approval rating among evangelicals stood at 61 percent. Yet this leapt to 81 percent at the polls. And today, in the culture war gripping the USA, the ratcheting up of rhetoric is increasing and it is drawing in non-evangelicals who make common cause with the US right.

This includes Archbishop Viganò, the former Vatican nuncio in Washington D.C. who, on 7 June, published an open letter in support of Trump and blaming the current crises gripping the world and the USA on a malevolent international 'deep state', and even a 'deep church' in alliance with it.

The letter first appeared on a Canadian ultra-conservative Catholic website. It was soon being promoted by the online platform 'QAnon'. This right wing source is pro-Trump, anti 'liberal media', promotes conspiracy theories, and presents the current conflict in the USA as representing 'good' (ie Trump) versus 'evil'. It has millions of followers, who have been associated with denunciations of Covid-19 as a fake or as a destabilizing strategy by an international secret conspiracy determined to damage Trump's re-election. This alliance of the Trump core-base, online far-right conspiracy theory promoters, and conservative evangelicals, with some right wing traditionalist Catholics is extraordinary.

Apocalyptic politics

The polarization of US politics and society is intensifying. In this, the evangelical-right and its political allies tend to describe the increasing conflict in apocalyptic terms. In a society where many no longer get their news from the mainstream media, the Trump-led campaigns to influence narratives should never be underestimated. Nor should Trump's ability to articulate the anger and anxieties of those sections of US society who form his base. In the intensifying culture war for 'the soul of America', a long hot summer is only just beginning.

Martyn Whittock is a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England and a historian with a particular interest in the interaction between faith and politics. His latest book, Trump and the Puritans (co-author James Roberts), was published in January 2020. It came out in the USA the morning after Trump's action at St John's Church.