Rector for Bansfield Benefice the Reverend Brin Singleton is involved in a major research project to record centuries-old graffiti in medieval churches across Norfolk.

He believes we have a lot to learn from these old inscriptions and that through them, modern churchgoers can engage with the prayers of previous generations.

Brin speaks here about how these medieval stone etchings underline a tangible faith, and his belief that Christians should look for the opportunity they offer to engage with God in a new way.

CT: How did you come to be involved in the project?

BS: I went along to a recording and that's where I had this sudden revelation that there was soft stone everywhere with graffiti through the generations. The big surprise for me was that these people weren't just tagging themselves, or saying 'I was here', but that the graffiti was saying something about these people's lives and their fears and then placing them next to God.

I've been trying to think what that means for our parish and the people who come to visit; looking at the church itself as a physical presence, a reminder to people of God's presence and as sacramental – an outward expression of inner grace. Post-Reformation we are sensitive to superstitions, but by etching these marks in a scared place, medieval people were giving their hopes and fears over to God, which I've found fascinating.

CT: Lots of the graffiti contains references to superstitions, such as curses and symbols to bring luck. Can you explain more about these?

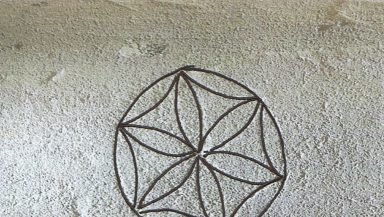

BS: The prayer book says we need to be cleansed of ills and the medieval understanding of this was that the world is inhabited by spiritual beings that want to harm us so we need to be cleansed of demons - even baptism was seen as a right of exorcism. Some of the inscriptions around fonts are circular and were meant to fool demons into chasing around in an endless circuit rather than attacking the baby.

As for cursing, the psalms are full of David cursing his enemies! And today we seem to have buried these practices, but for medieval people to curse in a holy place was to acknowledge mortality and weakness, and to give fears about that over to God. Today we're very guarded about making accusations against other people, and rightly so, but that doesn't stop us from being angry. By expressing that anger in a holy place, we're putting God in the picture.

CT: So do we have something to learn from these inscriptions?

BS: Yes certainly. These graffiti inscriptions are there, and people are interested and are going to come and see them, so we as the Church have got to put our side of things and what we find interesting alongside the academic views.

Perhaps it should be unsurprising, but these markings seem to suggest that earlier medieval parishes lived in a world where prayer mattered, and God was taught as being concerned about ordinary lives. It was part of an ongoing conversation, and seems to be an affirmation that people did express their prayer life in physical ways, and inscribing messages on walls was one of them.

Nowadays, often people feel that they can rarely engage with what God's doing in their lives, but that doesn't seem to be the case in the past. Today we use art and all sorts of media to convey theological thought and perhaps graffiti was the common expression of theological thought in medieval times!

CT: Matt Champion, leader of the research project, has argued that churches in medieval times were more interactive – people engaged with the fabric of the church physically – and they were perhaps more communal or community led in that way. What are your thoughts on that?

BS: For youngsters, we're now discovering new ways of engaging. Messy church is an example of an expression of that, and adults are learning to play with tradition and engage with God in a way that we perhaps used to but have lost touch with. I can't see any church plastering its columns and inviting people to etch in their prayers and petitions, but big boards to write on might be an interesting thing to help engage congregations in a new way. It's an interesting thought.

A survey of medieval churches in Suffolk is just about to be launched, and anyone interested in volunteering or learning more about the project is invited to visit www.medieval-graffiti.co.uk