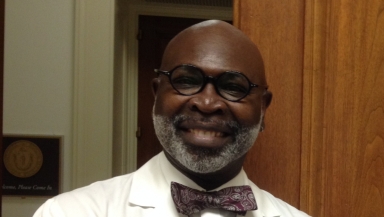

A US doctor who performs dozens of abortions a day has controversially defended the service he offers as a Christian 'ministry'.

Speaking to Christian Today Dr Willie Parker said: "[It is a ministry] to a degree that any effort that I exercise on behalf of other human beings in the context of the compassion that I feel I ought to have as a follower of the life of Christ."

Parker feels so passionately about this issue that he has given up his medical practice in Chicago and moved south, to provide abortions in Mississippi and Alabama, where opposition to abortion is at its strongest.

Over the last few years some of the southern states have tightened their abortion laws, resulting in the closure of a number of clinics. The clinic where Parker works in Mississippi is now the state's only clinic, and he is engaged in a legal battle to keep it open.

In July, Esquire magazine published a lengthy feature entitled 'The abortion ministry of Dr Willie Parker'. Unsurprisingly, it was met with severe condemnation from the Christian Right in America. Dave Andrusko described the article in the National Right to Life News Today as "a futile attempt to make a kind of saint out of a man who flies into Mississippi twice a month and performs as many as 45 abortions a day." Carole Novielli, writing for Life News, said: "Excuse me - Abortion Ministry? Are you kidding? How is the brutal murder of unborn children all-of-a-sudden a ministry?"

When it comes to the Church, Parker considers himself an "insider" but he isn't blind to the opposition from much of the rest of the flock. So how does he fit together his Christian faith with a practice that many Christians would describe as 'murder'?

A 'conversion'

Parker grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, and adopted what he calls the "fundamentalist Christian" views of those around him. He also grew up knowing that most around him believed that abortion was wrong. "While [abortion] wasn't taught against it was kind of implied that that was not the thing to do," he says.

At college, one of the first essays he had to write was about abortion from a Christian perspective. "Even though I had these fundamentalist beliefs, the best I could do was to say that it was a very complicated issue and I hope everyone approaches it prayerfully," he says.

But his views began to change while he was at medical school. "I never had an intention of leaving my religious beliefs behind, but I had to come to understand it in a different way." A way he describes as fitting with the "reality-based, science-based view".

In the first 12 years of his medical practice, Parker didn't perform abortions. In that time he wrestled with the knowledge of the religious perspective on the issue, combined with a growing conviction that some women needed abortions.

A pivotal moment came when listening to Martin Luther King's final sermon, in which he talks about the Good Samaritan. "[King] said that what made the Good Samaritan good was, rather than asking the question of the others, 'What will happen to me', the Samaritan asked 'What will happen to this person if I don't stop to help them?'"

"I had an epiphany," says Parker. "Rather than being more concerned about what will happen to me for providing the care – what will my fellow Christian travellers think of me – I became more concerned about what would happen to women when that care was not available, given that I already knew that when abortion care is not available, that women take drastic measures and they have serious injuries or they die."

He felt it was significant that the moment of "empowerment" came within a religious context, given that it was the religious view that was holding him back.

"I call it my personal conversion experience around becoming more concerned about others, and not allowing my religious understanding to be more important to me than my sense of humanity, which involved always being willing to act on behalf of another human being if I can."

Abortion as 'care'

The problem people have with this view is the idea of abortion as 'care', and that the best way to help a woman at a time of crisis is to offer her an abortion.

Parker says: "There is no aspect of helping another human being that goes beyond a Christian understanding." But many Christians oppose Parker's stance because they believe life begins at conception, and so by aborting a foetus you are ending a life.

So what is Parker's explanation? "To use religious language, life began when God gave the divine spark. It becomes very arbitrary to talk about some magic moment at which life begins.

"If you say that life begins at conception, I think you're too late in making that declaration. My position is that life is a continuum, it is not an event, and so life doesn't begin at conception and end at death – that is my Christian understanding. From a scientific standpoint, it's all a life process."

Like many abortion supporters or defenders, Parker points to the fact that a foetus does not have the same legal standing as a person. Though he claims he doesn't have to devalue the foetus in order to value the rights of women.

"I am not trying to be dismissive of the deeply held views about the reverence and sanctity of life that people who are against abortion. I hold that same sanctity about life. But what is also sacred for me is the personhood of women."

When it comes to the biblical perspective, many would point to Psalm 139 where David writes: "you knit me together in my mother's womb".

But Parker is critical of those who "take literary devices and elevate them to the status of canon law." He says the science of the day would have given women had little agency in a pregnancy, but would have recognised the woman only as a carrier of a man's 'seed'.

And although he says he is reluctant to point to scripture to back up his own perspective "because part of the mischief that's done is people pull a passage out of scripture and use it to make their point," he does look to scripture to find a theology of choice.

He points to Joshua 24:15, and the words: "choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve [...] But as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord."

"What is sacred about that passage for me," says Parker "is the element of choice, and being self-determining and autonomous – to me that is the part of us that is most like, in the Christian understanding, the creator."

Facing reality

The arguments both for and against abortion can obscure the fact that the procedure is not pleasant. In Parker's terms "we disrupt life processes". There are many other ways to describe it.

A medical abortion can involve taking a pill, leading, effectively, to a miscarriage. A surgical abortion means extracting the foetus by suction. The additional problem people have with late-term abortions is that you are no longer terminating a non-viable pregnancy, but a foetus that could easily be called a baby.

The clinic where Parker works in Mississippi performs about 2,000 of the 6,000 abortions done in the state each year. Because Parker divides his time between different clinics, he can sometimes perform up to 45 abortions a day.

But what does that feel like – to spend a day extracting foetuses?

"Have I been able to reduce myself to an automaton? The answer is no.

"I have not had any desire to reduce it to a process. I do maintain the objectivity of a physician [...] the same objectivity I used to have when I delivered babies."

But he does choose to focus on the women he feels he is helping. "Have I found a way to be present and respectful of the process that I am participating in, and to be respectful of the agency of the woman? Absolutely. Does that require me to delude myself about the process of what we're doing? No."

The Christian response

Parker doesn't need to be told that people disagree with him. He knew George Tiller, the doctor who was shot dead at his church in 2009 by a pro-life activist.

"I am very much aware that people feel strongly about this issue, to the point of being willing to harm others, which is kind of ironic – an irony of being willing to kill on behalf of life," says Parker.

He has chosen to be public about his work; many in a similar position would not. The two other doctors who work at the same clinic in Mississippi do not disclose their identity.

So far, any threats against him have only been 'warnings'. He says: "People have decided that because I provide abortions, that I am void of compassion, that I am not of high medical competence [...] that I don't care for women. These are all psycho-terrorism as I call it."

There are others who have more peaceful methods of opposition, but who also feel he's gone astray. "Many people say they are praying for me," says Parker, "or they think I have lost my way, and they are praying for me that I find my way and that I come back to Jesus... I choose to see that they are coming from a place of compassion."

Parker has looked to writers such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer to help him think through his opposition to the norms of Christian culture. From Bonhoeffer he said he learned about being "present and accountable in a world that required drastic action".

"Those actions didn't appear to be on the surface very conventional Christianity, but [Bonhoeffer] was able to conclude that he needed to act in the world in a way that would act on behalf of the greater good," says Parker.

Presbyterian minister Harry Emerson Fosdick also influenced his thinking on this, particularly his 1922 sermon 'Shall the fundamentalist win?'

"[Fosdick] said that because of the nature of faith, particularly the Christian faith, it is quite possible for people to believe the Bible literally and people who are equally Christian and deeply observant of their faith to not take a literal approach to the Bible. And because of that there is possibility within a faith community for there to be what appear to be diametrically opposed views, but one doesn't invalidate the other."

But despite the differences, Parker still considers the Church his family. "I consider myself, when it comes to Christianity, an insider," he says. "And in the way that there are disputes within families, you love each other enough to criticise one another."

One criticism he has is that he feels the Church has been "misguided", and at times "on the wrong side of social issues," such as slavery and homosexuality.

In practice, his opposition to some prevalent teachings within the Church has meant being selective about his choice of local church, both to avoid putting a minister in a difficult position, as well as the opposition he might face personally.

Meanwhile, he has looked to the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, of which he is on the board, for like-minded community. "It's important for me to have connection with a faith community that does not practice a zero sum game between dealing with current social issues and trying to maintain the authenticity of their religious practice," he says.

Parker sees the politics of many churches in the south as a foregone conclusion. As evidenced by their reaction to his views, they are unlikely to be swayed by his inclusive rhetoric.

Indeed, the majority of Christians will not agree with Parker's position. The question instead will be the degree to which they disagree. Is he a baby killer complicit in evil; is he following a sincerely held belief, but nonetheless misguided; or is he demonstrating Christian love in what some would see as a God-forsaken place?