Shakespeare's brilliance lies in his characters. His plots were almost entirely borrowed – for instance, Hamlet and King Lear were re-makes of earlier plays; Romeo and Juliet re-tells an Italian story; the English history plays are based on sixteenth-century historiographies like Holinshed's Chronicles; the Roman plays are built from ancient sources like Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans.

Many of these stories were already known to Shakespeare's audience. If Shakespeare were a filmmaker today, he would be known as an artist who primarily re-makes classic films. If he were a singer, he would be known as one who specialises in cover songs.

So Shakespeare's audience didn't go to see his plays for the thrill of a suspenseful plot. Instead, the drive of Shakespeare's plays comes from the intensity of the characters he created. Shakespeare had a gift of perception, able to observe and comprehend human emotions and behaviour with keen insight. And he had a talent for expressing these observations with exquisite verbal precision.

One aspect of human experience that clearly fascinated Shakespeare was religion. It would be easy to say that Shakespeare is a religious writer because he lived in a religious age. To a degree that is difficult for those of us in the secularised West to fully appreciate, sixteenth and seventeenth century English culture was saturated in religion.

Politics, science, literature, music, daily habits, communal culture and even the weather were experienced through religion. This is not to say that everyone was devout. Then, as now, there were people who thought deeply about their faith and those who didn't really care, but the social fabric for everyone was inescapably Christian.

The historian Christopher Haigh has written about this in The Plain Man's Pathways to Heaven: Kinds of Christianity in Post-Reformation England, 1570-1640 (Oxford, 2007). Haigh's title comes from a pamphlet published in 1601, Arthur Dent's The Plain Man's Pathway to Heaven. This remarkably popular text (25 editions by 1640) presents a dialogue between four characters: Theologus, a divine; Philagathus, an 'honest man'; Asunetus, an 'ignorant man'; and Antilegon, a denier. This pamphlet is helpful for understanding the religious climate in which Shakespeare was working.

It is of limited use to understand the period in terms of a binary of religious vs secular. Rather, within this emphatically Christian culture there was a range of religious behaviours, practices and beliefs. Then as now, these were also not fixed identities. Individuals underwent conversions, periods of devotional intensity or ennui, periods of doubt and disbelief. Shakespeare, like his contemporaries, were intrigued not only by different types of Christians, but also by the 'pathways', the twists and turns of a religious life.

It is also of limited use to understand the period in terms of a binary of Catholic versus Protestant. There were certainly polemicists during the time that strove to polarise the religious culture, those who wanted to emphasise the distinctions between Catholic and Protestant, sometimes for political ends. But for many people, elements of Catholicism and Protestantism were more blended. Centuries-old parish traditions could meld with new theologies. It is important to remember that the changes introduced by the Reformation were often implemented in medieval churches – theoretical innovations could meet their limitations in an architectural space designed for a different liturgy. The literary scholar Jean-Christophe Mayer has written of 'Shakespeare's hybrid faith,' and it is a useful mode of thought. Instead of conceptualising religious identities in the period as boxes to be checked (Catholic or Protestant), it is helpful to think through hybrids and spectrums.

If we put all of this together – that Shakespeare's brilliance lies in his characters, and that religious identities in the period were fluid and varied – what do we find when we turn to Shakespeare's plays? We find, in a trendy sixteenth century word, a hodge-podge. We find characters who are doubters and devout, spiritually intense and spiritually vacant. These qualities can be spread across characters or concentrated in just one individual.

It is difficult to parse out Shakespeare's religious characters from his non-religious ones, since those are our categories, not those of Shakespeare or his audience. One of the characters who quotes the Bible most extensively is Falstaff, the obese and usually drunk king of merriment in the Henry plays. Does that make Falstaff devout? One character who shows the most fervent devotion is Romeo – but his adoration is directed at Juliet. Cast in the language of worship, is Romeo's love thus religious? Hamlet perhaps thinks the most about the nature of truth, and he has been studying at a university (Wittenberg) associated with the Protestant Reformation, yet he doesn't concern himself much with religion per se. Meanwhile his uncle Claudius, the play's unethical villain, gives us a powerfully raw scene of prayer.

What makes the religiosity of Shakespeare's characters powerful, and even palpable, is not that they fit into categories but that they are on a pathway. Characters change in their faith, not always to become stronger. We live in a narrative world that has been shaped by the novel, and especially the Bildungsroman, a novel that traces the development of a character, usually in a way that shows positive progression. The expectations of Shakespeare's audience were different. A faith journey was not always a from-to experience; it was often just a going-through experience.

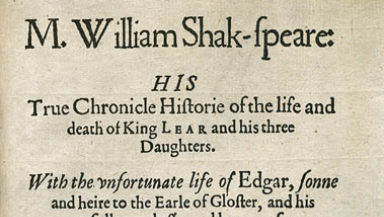

As an example of this, we might take King Lear. Lear's spiritual journey is one of the most accessible. For much of the play, he suffers by mistaking his ego for God. The play opens with him playing God by dividing his kingdom and setting up a 'love test' for his three daughters; it is a fantasy of absolute power and being glorified by others. In the famous storm scene on the heath, the audience might see Lear's vulnerabilities – he has lost his home and his hold on power, and is at the mercy of the elements – but Lear continues even then to command nature as if he were the reigning deity. The experience, though, proves a transformative one. Lear is, as Rowan Williams might put it, broken open in a moment of empathy, as he suddenly recognises, suddenly can see and feel, the plight of the poor:

Poor naked wretches, wheresoe'er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? (3.4.28-32)

There is not only a change of heart, but a change of tone. The king who barked in imperatives and hyperbole for most of the play finds a simpler speech and sentiment: 'Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel' (3.4.34). If this were Dickens, this breakthrough in radical compassion would shift the fate of the character. But not here. Lear ends perceiving himself outside of others' empathy and divine justice: 'O, you are men of stones. / Had I your tongues and eyes, I'd use them so / That heaven's vault should crack' (5.3.231-33). Lear may have been cracked open, but he doesn't see that heaven has been. Kent's response to Lear's death – 'Break, heart, I prithee break' (5.3.287) – renders the broken heart a sign of alienation, not empathy. Cordelia has often been seen as a Christ-figure, but Lear's final cries – 'Howl, howl, howl, howl!' and 'Never, never, never, never, never' (5.3.231, 283) – are an anti-hymn of gut-wrenching religious despair.

And then there was a jig. The fact that most of Shakespeare's plays were followed by a jig is an under-appreciated fact about his theatre. But if we are to contemplate what we take away from the plays it is useful to remember that they all end in a lively dance. Shakespeare's characters exhibit moments of radical compassion, gut-wrenching religious despair, and (although not in King Lear) moments of joyful gratitude to God. These are not states or identities, so much as they are moments in the collective dance of religious devotion.