Zimbabwe's church played no role in kicking out Mugabe. That could spell trouble for the future

The ousting of Robert Mugabe has led to jubilation on the streets of Harare. Delirious Zimbabweans have sobbed with joy into the cameras and microphones of foreign correspondents, ecstatic that the 37-year rule of the dictator has ended.

But serious questions remain over the post-Mugabe future of Zimbabwe, particularly as the group which has so often fired the resistance to the ailing despot's regime has been effectively sidelined.

Zimbabwe's churches and Christian leaders — frequently the focal point for opposition to Mugabe's excesses — have played little to no part in the removal of the former president. And their inability to wrest back control of the anti-Mugabe movement suggests the country's future may not be as bright as the celebrating citizens of Harare hope.

Until the army's bloodless coup on Wednesday last week, the most recent opposition to the Mugabe regime came last year when a little-known pastor called Evan Mawarire sparked months of protests with a defiant Facebook video condemning the poverty, hunger, and unemployment racking Zimbabwe.

Arrested several times and denounced by Mugabe as a foreign stooge, the protests which had gathered around Mawarire's #ThisFlag hashtag fizzled out by early 2017.

Now, as the military has achieved what he could not, Mawarire has been calling for Zimbabwe's citizens to take over the transfer of power and not leave it to the country's generals.

'We must not take our eye off the ball in making sure that our constitution is not violated, in making sure that democracy is maintained as the preferred way to govern our nation,' he said last week in a message live-streamed over the internet. 'Are we there to sit and wait or there also to play a role?'

The politicians who successfully negotiated Mugabe's departure are only interested in power not the people of Zimbabwe, of whom 85 per cent are Christians, Mawarire said.

The former opposition leader's irrelevance to the current process underlines the truth that the coup was launched by the army not to overthrow Mugabe's corrupt and cruel regime but to ensure their preferred successor, the sacked former vice-president Emmerson Mnangagwa, takes over as president.

As a result, those like the church who opposed Mugabe because of the terror and poverty his rule inflicted on Zimbabwe have been largely sidelined. The real power brokers are now the coalition of forces centred in the military, security services and veterans' organisations, whose chief aim is to prevent Mugabe's controversial second wife Grace from inheriting the presidency.

Other Christian leaders have also tried to insert their concerns into the unfolding endgame of Mugabe's reign, but with little success. In a statement, the Zimbabwean Council of Churches insisted they were not powerless in the face of the internal squabbling for power within Mugabe's ruling ZANU-PF party.

'We see the current situation not just as a crisis in which we are helpless,' the statement said. 'Our God created everything out of chaos, and we believe something new could emerge out of our situation.'

Another umbrella church group, the Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations which brings together the three main denominations of Catholics, Anglicans, and Evangelicals, said in their own statement that 'the wheels of democracy' had got stuck in the mud and the citizens of Zimbabwe had been forgotten.

'It is this lack of democratic renewal and the resulting stagnation, sterility and fatigue that has culminated in the current situation,' it said. But the statement also admitted Zimbabwe's Christians had taken their eyes off the ball and allowed the generals to wrest control of the anti-Mugabe movement, saying: 'The church has lost its prophetic urge, driven by personality cults and superstitious approaches to socio-economic and political challenges.'

The church leaders' statements reveal their well-grounded fears that Mnangagwa, who has already been selected to replace Mugabe as president, will not usher in a new era of democracy and respect for human rights.

Dubbed the Crocodile for his cunning and guile, Mnangagwa is accused of atrocities during Zimbabwe's bloody civil war in the 1980s and is suspected of leading the violent repression of opposition parties after the disputed 2008 election.

It is hard to imagine the new Zimbabwe hoped for by citizen and church activists appearing under Mnangagwa's regime, underlining the fact Mugabe's ousting was an internal ZANU-PF palace coup rather than a true revolution.

Mawarire's #ThisFlag protests were not the first time Christian leaders have found themselves standing up to Mugabe, himself a practising Catholic.

The Catholic Archbishop of Bulawayo, Pius Ncube, often spoke out against the regime's terror, particularly drawing attention to bloodbaths of his native Ndebele people.

And the Anglican church has also frequently been at loggerheads with Mugabe, in particular with the violently pro-regime former Bishop of Harare, Nolbert Kunonga. Kunonga attempted to split the church and weaken it as a powerful anti-Mugabe voice in Zimbabwe, and inflicted a campaign of violence and coercion on clergy who refused to follow his breakaway faction.

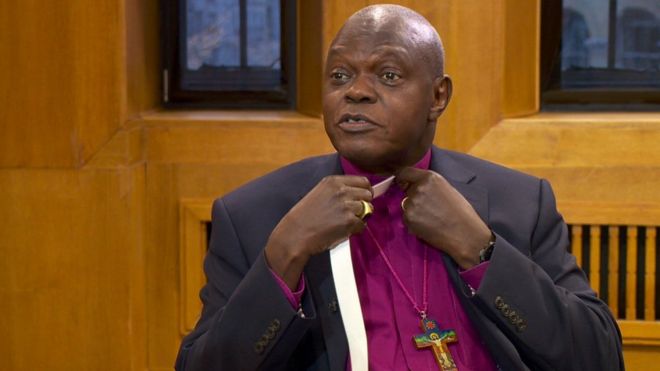

In 2007, the Uganda-born Archbishop of York, John Sentamu, cut up his dog collar live on TV in protest at the suffering Mugabe had inflicted on his people, vowing not to wear it again until the president was gone.

Returning to the Andrew Marr Show, ten years later, Dr Sentamu declined the offer to put on the shredded pieces of the old collar, preferring instead to put on a brand-new one.

'I could attempt to put this one back together using superglue, but it would be a pretty ropey collar,' he said. 'And I actually think the message for Zimbabwe is the same. They just can't try and stitch it up. Something more radical, something new needs to happen.'

Mawarire has now returned to street protests, recently taking part in demonstrations in Harare. But as the handover to Mnangagwa proceeds apace, other church leaders have continued to try and sketch out an alternative future.

The general secretary of the Zimbabwean Council of Churches, Kenneth Mtata, told the Church Times that the church needed to proclaim a better vision for his nation. 'The churches need to continue [saying] "Another Zimbabwe is possible."'

Tim Wyatt is a freelance journalist specialising in faith and religion.