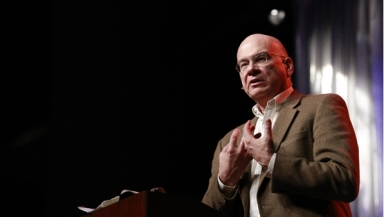

Dr Tim Keller is the founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church. He is ranked among the most influential preachers and Chrstian leaders in the world.

In 1989 Keller helped lead a prayer group of 15 people in an apartment in the Upper East Side of New York, and together they explored planting a church in the area. Now, the church has a regular Sunday attendance of more than 5,000 people meeting in multiple congregations. Keller is in demand as a conference speaker all around the world and has authored numerous books including the New York Times bestseller The Reason for God. He was in the UK recently taking part in the Proclamation Trust's Evangelical Ministers' Assembly. Christian Today caught up with him about his latest book, Preaching: Communicating Faith in an Age of Scepticism.

I was surprised to hear that you received a C grade for your preaching class at seminary. How did you know that you were still called to be a preacher?

If you go into the ordained ministry, there are plenty of opportunities for people who are not great at preaching. I was not certain how prominent the preaching component of my ministry would be as there are plenty of ways to minister the word of God. It turned out to play a bigger role than I thought.

So how did you know you were called into ministry?

I became a Christian in college through the ministry of Intervarsity Christian Fellowship [in the UK it is called UCCF]. Almost immediately I got involved in the fellowship and the work among other students. I felt an affinity for student ministry almost right away. After two and a half years of ministry leading small groups, Bible studies and talking to people about faith, I really, really liked it and became a leader in it, and that is what gave me an interest in pursuing a call to ministry.

I was struck in your new book by the way you advocate an approach to preaching that is always apologetic, evangelistic and pastoral at the same time. Why do you think this is particularly needed in the Western Church today?

On the one hand preaching is a communication of information that takes clarity and a certain amount of the exercise of reason. But we do not live in a highly rationalised age, we live in an age where people are probably more influenced by their experience than their reason. Therefore if we are going to demonstrate the authority of the Bible, we don't do it by telling people that the Bible is authoritative. We do it by using the Bible to reveal people's own hearts to them. I see my role as showing people the power of the Bible - using the Bible to show that it [and it alone] will help them make sense of their feelings and their problems and their experiences. When they say "that's right", we are showing them that the Bible understands them and changes them. We are almost group counseling people. Unless we show people how the word of God works in actual life they are not going to believe it.

What would you say to someone who said that their calling is to be a pastor and teacher and so they wouldn't see the evangelistic task as a necessary part of their pulpit ministry?

That's a good question. There is a diversity of giftedness in gospel ministry. You could say that gospel ministry has a prophetic, a priestly and kingly aspect to it. The prophetic is the speaking and preaching, the priestly is more of the counseling and pastoral side. The kingly is more of the leadership role. We all know that nobody is equally gifted in all of those areas, even though they are all aspects involved in the ministry. Some people are better at building up the saints than they are at talking to unbelievers, while others are unusually good at talking to nonbelievers. But you can't just say, "That is not my gift." If a gospel minister is not good at administration, they still have to improve their leadership skills. If a person is not very good at public speaking they still should do everything they can to enhance those skills. If you say that you are not very good at talking to non-Christians, we have to realise that we live in a society where even on a regular Sunday morning worship service we will have a variety of people present; some will be believing while some won't believe. When you minister the word you have to minister to everyone present. The burden of my book is that we need to be better at thinking about the non-believing person or secular person sitting there listening to us speak. We need to understand their beliefs, their doubts and their objections and take them into consideration as we are preaching.

Do you think that might be what Paul is getting at in 2 Timothy when he tells Timothy to do the work of an evangelist, even if he might not be a 'natural' one?

Yes, right. There's a difference between a role and a gift. Evangelism is a role that actually all Christians but also all ministers have, even though evangelism is not a gift that all Christians and ministers have. So those people who are not gifted in a particular area need to dutifully and as joyfully as possible work at it, even if it doesn't come easy to them. I think that is exactly what Paul is doing in 2 Timothy. I wouldn't think Paul would have to exhort Timothy to do evangelism if he was naturally gifted at it. There's no reason to tell someone to do something if they are already doing it. There are indications that Timothy had a more retiring personality.

I'm a regular listener to your sermons. It feels sometimes that your assumed listener is an individual person rather than the church community or families. Is that intentional because of your evangelistic passion or is it related to the kinds of people that you have coming through your church?

I think you are right. There are some times that I address the community as the community. But in a large urban church, lots of the people are only there for a while. Lots of people come for a couple of years while they are at college. Of course there are also lots of non-Christians present. That is the reason why fairly often I am speaking to individuals who I know are there for the first time and do not consider themselves part of the body. It's a trade off. I would like to be talking to the body more. In some cases churches that are more cohesive and stable have trouble bringing non-Christian people in and including them. There's a downside to every model.

Often some of the finest communicators are pastors of larger churches and so those are the ones we tend to hear from at conferences and events. We also borrow many of our models of church and ministry from larger churches. Could we be missing the value and benefits of smaller churches?

I am a big believer that there are many many things that smaller churches can do. When I am on holiday in the UK I deliberately choose to go to a small Baptist church where the average attendance is 15-20 people with a lay minister. Everyone prays. During communion everyone thanks God. Everyone prays aloud about their various issues. Its wonderful. People notice who is there and who is not. So if you are a visitor you are really welcomed and if you are missing everyone calls you up and asks how you are doing. A large church can't reproduce that. We are very wrong to idolise the large church models.

In light of the collapse of Mars Hill in Seattle after Mark Driscoll left and the plummeting numbers at Mars Hill in Grand Rapids after Rob Bell moved on, how can preachers make sure they are building strong churches and not just preaching ministries?

I think that any church that gets really remarkably large under a founding pastor is something of an unstable compound. The same sort of thing happened to Westminster Chapel after Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones left and a similar thing happened to the Metropolitan Tabernacle after CH Spurgeon left. I am not sure that it is completely avoidable. I can tell you what I have tried to do as a founding pastor of a large church. We have divided the church into three congregations and put a pastor and a staff over each of the congregations. I share the preaching. I only preach half the time. One week you get me. One week you get the local pastor. In about two years I step out and those churches belong to them. We have done this rather to try and find a successor. Because with a founding pastor who grows a big church everyone is there because they like the founder. If you don't like the founder then you are not there, so the founder is the one glue for the church. So how in the world could one person step in and take the founder's place? But what if you could have three successors instead, so hopefully people will have preaching that they enjoy and a community they like. So rather than try and continue it you break it up and hand it off to a group of people.

You seem committed to preaching live in the room with people, rather than by video relay. Tell us about the theology behind that.

Preaching is something that happens in a community. I need to be in that community. The body matters. My presence matters. The congregation responds as I speak. They might be quiet, they might be crying, they might be restless. Then I respond to them. I might say something and I can tell by the silence that I have hit a nerve so I decide to stay there for a while. That is dialogue. That is interaction. They are communicating with me and I am communicating with them. If I am just getting beamed into some place then I can't respond to them or adapt to them. My understanding that preaching is the preacher and congregation together being in the presence of God means that both I and the congregation are part of the ekklesia, the assembly of God. How can I preach to people if I am not actually part of the assembly?

I really like the fact that you often mention Kathy, your wife, both in your book and in your preaching. You describe her as your best critic and the most ardent supporter of your work. What advice would you give to preachers' spouses?

Kathy and I met in theological college. She therefore does have an advantage over some other spouses as she is theologically informed. It doesn't mean however that the interactions haven't been hard and stormy. You are really vulnerable after you have poured your heart out preaching. If you then ask your spouse what they think and they say "Meh...I don't think you really drove the point home", it's going to be hard. They need to be gentle and show some bedside manner. For many preachers this is the main thing that they do in life, so if you fail at preaching you feel like you are failing at life. Having said all that, the preacher will sometimes be unnecessarily hurt or crestfallen. If the preacher is too sensitive to take the feedback or the spouse is too intimidated to give it then this could be a fault in their character that they might need some help with or even need assistance to grow their marriage in this area. I would say it is a good idea to try and develop the relationship so that you can have these kinds of conversations.

Going back to that C grade you got from your seminary course in preaching. What advice would you give to that younger you just starting out in ministry?

It takes a long, long, long, long time and lots and lots of practice to become as good a preacher as you are gifted to be. There's a tendency to think if you are gifted then you can just do it. But I preached three different expositions a week, 50 weeks a year for nine years when I was 24-33. I did 1,500 expositions by the time I was 33. I then went to Westminster Seminary and taught preaching for five years. Then I went and started Redeemer in New York. I thought I was as good a preacher as I was going to be. But Redeemer was a crucible for me and my preaching because these were harder people and their feedback was more negative. There were a lot of smart people here and it was very challenging. I could see myself growing enormously in my early 40s even though I was preaching from when I was 24. It took me thousands of sermons to get to the level that God had gifted me to get to.

Tim Keller's new book Preaching: Communicating Faith in an Age of Scepticism (Hodder and Stoughton) is out now.