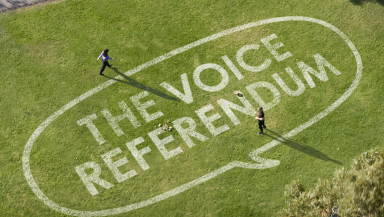

We were warned. "If you vote against this, then in the eyes of the world, Australia will be viewed as a backward racist country." The 'this' was the Voice referendum which sought to re-write Australia's constitution to give specific recognition to the Aboriginal people, and to establish a voice to parliament for them.

Apart from the fact that the world has more than enough concerns on its plate just now, is there any truth to this assertion? Should the world regard Australia as racist? And now that the dust has settled on what was a somewhat heated debate, what can the Church learn?

The result was not supposed to be in doubt. When the proposal was first announced it enjoyed up to 70 per cent support in the opinion polls. With government backing and the vast majority of the corporate world, media, all the celebrities who spoke out (whether sporting or entertainment), academia and all the civic elites – it should have been a dead cert 'yes'.

The Yes campaign, funded by large donations from some of the big corporations, had ten times the money that the No campaign had. Everywhere I went in Sydney I was bombarded with Yes propaganda. No one in my up-market area dared have a No poster up in their backyard. Sydney City Council kept flying flags telling us to vote Yes. My utilities and internet companies assured me that they were on 'the right side of history'.

Even the denomination I work for, Sydney Anglicans, politely asked us to 'prayerfully consider voting Yes'. And when I went to the Sydney Opera House, we were treated to a mini sermon from the orchestral leader telling us all to vote for 'Voice, treaty and truth telling'. No one was in any doubt about what the great and good in our society wanted us to do.

Only, the Australian people didn't listen. Despite all of this, over 60 per cent voted No. Every state voted No. (To pass, the Voice needed to get a majority of votes and in four out of the six states.) It was an astonishing result - on a par with Brexit. But it was not just the result which mirrored Brexit. It was the enraged excuses that came from the civic elites who are not used to having their moral and intellectual superiority rejected. The same pattern was followed.

The first meme was that those who voted No did so because they were 'misinformed'. Just as in Brexit the majority of 'university educated' people voted Yes to the EU, so the majority of 'educated' people appeared to have voted Yes in the Australian referendum. Those who believe themselves to be 'educated' regard those who are not as being ignorant and open to misinformation. The trouble is that this correlation doesn't necessarily follow. What if being 'educated' just simply means that you have been indoctrinated into the values and doctrines of your educators, and have no more capacity to rationalise and think through things than ordinary mortals?

There is some research which suggests educated people (in the modern sense of education) are less likely to change their minds on the basis of evidence and reason, than those who have not had the privilege of being educated in cultural Marxism, critical race theory and Queer theory! Just as in Brexit the Russians, the Daily Mail and Rupert Murdoch were blamed, so in the Voice it was 'foreign powers', social media and again the omnipotent Rupert Murdoch who got the blame.

In fact some regarded our 'educated' people as being so sensitive and impervious to reason and rational thought that they needed special help to cope with the result. Australia's cricketers were offered counselling, and civil servants in Queensland were given compassionate leave if the result was too much for them!

The second meme is that those who voted No were not just ignorant, but racist. Remember that in Brexit, those who voted No to the EU were accused of being 'little Britons'; racist people who just didn't like immigration and foreigners? So, the equivalent was said about No voters here in Australia. The old Brexit meme was trotted out – "We are not saying that everyone who voted No to the EU/the Voice were racist, but every racist voted No." The fact that this was demonstrably false didn't stop even Christians from stating it as a fact! It seems as though some 'misinformation' is acceptable if it is the 'right kind' of misinformation. The BBC dutifully 'reported' that it was racism which was the key factor. They were misinformed.

Consider these two facts. Firstly, there were many people who voted No precisely because they wanted to stop a racist/racial element being introduced into the Australian constitution. Very few people were opposed to the constitutional recognition that the indigenous people were here first – it was the idea of setting up a separate constitutional body based on race which was the cause of the rejection. When the white people in power in South Africa wanted to set up constitutional 'separate racial development', people in the West rightly regarded such apartheid as racist. But when the idea of a race-based constitutional body was floated in Australia, suddenly it became the 'progressive' thing to do. This became the most potent argument against the Voice and again, as so often happens in contemporary society, those in power decided to change the meaning of language.

Suddenly it was no longer about race but about recognising 'First Nations' – a term introduced to Australia from Canada and the US. It was no longer about skin colour and race, but rather about how you identify. The problem then becomes who qualifies as indigenous? If three of your grandparents are Scots or Irish and the other is Aboriginal, then are you the oppressed or one of the oppressors? Identity politics and race are a toxic and divisive combination. Especially in a society where 99 per cent of the claimed indigenous population of 800,000 are mixed race.

Secondly, there were significant numbers of indigenous people who were opposed to the Voice, despite us being 'misinformed' that this was the settled will of the indigenous people. Senator Jacinta Price, an indigenous woman, was the leading light of the No campaign. Ironically, she was racially abused and labelled a 'coconut' (black on the outside, white on the inside), just because she was 'the wrong kind' of indigenous person.

She spoke clearly and passionately about why she wanted all Australians to be the same. She did not believe that the significant problems which exist within much of the indigenous community would be solved by the Voice. And she was not alone. Although we do not have precise data, the last opinion poll before the referendum showed that around 40 per cent of indigenous people were opposed.

It is surely not without significance that the constituencies with the largest number of indigenous people voted No, whereas the wealthy largely white middle-class constituencies, with no indigenous communities, voted Yes. (There is evidence that the small percentage of indigenous people who live in areas served by remote polling booths, voted overwhelmingly for the Voice).

Although the Voice referendum will hardly register outside Australia, despite all the hyperbole, it was important and there are lessons to be learned for all Western democracies – not least the toxicity of mixing race with identity politics. Why is it that so many cultural elites seem determined to accuse their own countries of being racist? Is it genuine remorse and repentance, or just self-righteous blaming of the 'other'?

There are also lessons to be learned for the Church. With Brexit the Church of Scotland told us that God was for the EU (although he seemed unable to make up his mind about Scottish independence) and the Church of England bishops were absolutely certain that being in the EU was God's will (although they struggle with God's institution of marriage). With the Voice it seemed as though most churches and Christian organisations, from the Anglicans and Catholics to Tearfund, were for. Why? The churches were either out of touch with their people, or the people who attend church are not representative of the majority of Australia.

Whatever the reason it is surely an important lesson for the churches to learn. We should not speak clearly or pronounce on political matters which God has not made clear in his Word – otherwise we run the risk of further alienating ourselves from the people we are supposed to be reaching. Our job is to proclaim the Word, to say what God says and then to apply it to our own society – not to come down on one side or another on contentious and complex political issues.

This is not to say that the Church has nothing to say about racism or poverty, but we can only say what God says and not give divine authority to our particular political solutions. Nor is it to say that individual Christian leaders should say nothing about those political solutions, but they do so as citizens, not as prophets. The prophets say what God says; the politicians say what they think the people want to hear.

Meanwhile pray for Australia and especially for the indigenous people, who percentage wise are the most Christian of all Australia's ethnic groups and who face significant problems. More than one church leader spoke of how the Voice was an opportunity for reconciliation in Australia. It wasn't. True reconciliation was not going to come through a political body, however well intentioned. True reconciliation only comes through Christ and listening to his Voice. He is the one we must proclaim.