The link between law and love

Jewish academic and Hebrew scholar Irene Lancaster explores the fundamental connection in Judaism between law and love.

As we celebrate Pesach, people would be forgiven for feeling confused. What's it all about? Is Judaism a faith, a religion, an ethnicity, a people, a land, a nationalism, a diaspora, a particularistic way of life which is open to the other, a provocation, or even a 'crime against humanity'?

More importantly, maybe, can Judaism, whatever it is, even carry on existing? Is it really a 'provocation', a 'crime' to be attending Shul on Shabbat in London, and to be threatened with police arrest for simply crossing the road, for simply appearing to be 'openly Jewish'? And why doesn't the BBC even mention Pesach (Passover), while continuing to weaponise Ramadan?

We all know the answer to these questions. Decades of appeasement of the enemies of civilization have done their work only too well. But, keeping one's head down and being 'nice' simply does not work. Giving all our chametz to food banks and churches doesn't work. Leaving a chair empty for the hostages still in Gaza, including two babies, also doesn't work to help Jews in diaspora. But that doesn't at all mean that we should give up on giving.

But a new book about Judaism goes at least some of the way to explaining at least the basics. Rabbi Shai Held of the USA has just completed his new book entitled Judaism is about Love, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The cover of this book about Judaism and love has been carefully chosen: purple and gold, but of the softest hue. The book may be of regal proportions, but it's not showing off. And both the depth and the breadth of endorsements demonstrates the serious intent of the author and the appreciation people from different backgrounds feel for all his endeavours. Yes, it does seem to me that Rabbi Shai Held (who I don't know at all) and his book have gone a long way to eliciting love from perfect strangers.

I first came across the work of Rabbi Shai Held thanks to my friend and bibliophile Jonathan. I then utilized some of Shai's novel insights for teaching purposes, including our two Jewish Christian dialogue groups, as well as for a Zoom training course I was asked to deliver during Covid to Church of England clergy.

The main thesis of the book is that Judaism is about love, love of G-d, love of the neighbour and love of the stranger. The highest achievement is to 'live with compassion.' This is equivalent to 'walking in G-d's own ways.' If this seems a bit surprising, it's because in his view 'centuries of Christian anti-Judaism have profoundly distorted the way Judaism is seen and understood, even, tragically, by many – probably most - Jews.'

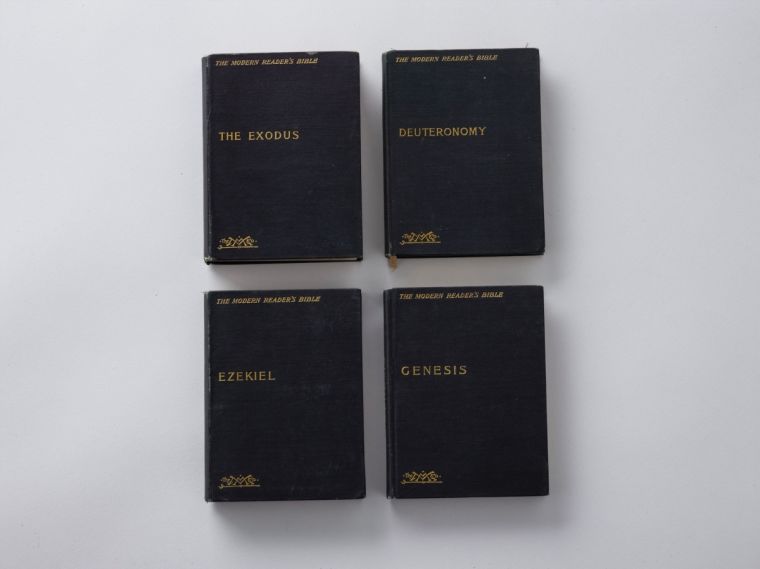

Shai points out that in Judaism's daily liturgy, the Shema, the most important prayer of all, which starts 'Hear oh Israel....', we first state that G-d love us and then recite Deuteronomy 6:5, 'And you shall love the Lord your G-d with all your heart and with all your being, and with all your might.' We Jews recite this all the time, and even have a mezuzah on our doors with the words inside the case, so how could we forget and not internalise these teachings?

It is not uncommon for a false dichotomy to be set up between Christianity supposedly being about 'love' on the one hand, and Judaism being about 'law, or justice' on the other. This has resulted in some Christian thinkers creating a 'theological discourse about the supersession of a loveless Judaism by a loving Christianity.' And this view has often been tacitly accepted by many in the Jewish community as well. But what we have to think about is: what is the root of law and justice? In Judaism, the root of law and justice is love itself.

Jonathan Sacks, in his book Lessons in Leadership, cites the Roman Catholic financial journalist and former editor of The Times, William Rees Mogg (1928-2012), who recognised that what makes Judaism unique is its legal system - wrongly criticized by some Christians as 'drily legalistic'. In fact however, Jewish law 'provided a standard by which action could be tested, a law for the regulation of conduct, a focus for loyalty or a boundary for the energy of human nature.' In other words, Jews have 'a system of self-control', by turning ideals into 'codes of action.'

It is also simply not the case that the 'Old Testament', ie Tanach or the Hebrew Bible, is 'angry, vindictive, and bloodthirsty', in contrast to the New Testament. Judaism is actually a religion of both love and law, of both action and of emotions. Jewish liturgy, as stated above, reminds us daily that 'Jewish law is itself a manifestation of divine love, not a contrast or an alternative to it.'

Jewish texts themselves 'push us to love both more deeply and more widely.' Community is all-important in Judaism. Loving our neighbours means that we 'want them to flourish and to contribute in meaningful ways to making that happen.'

For instance, my own next-door neighbour has just given me for my birthday one of the greatest gifts I could have, a framed photo of my family in Israel, which she downloaded from my Whatsapp page. That showed real love in my view. She knows my family are currently in great danger; that I have just visited them at a very difficult time for the country, and she knows that I miss them. What an amazing gift from a loving neighbour.

For Shai, love is emotion and action conjoined. It is a 'disposition', an attitude to life.

That love is not earned, but is a given. The prophet Hosea tells us that it would be a positive step if we could live up to that love. Moreover, the life of every human being has value. On self-worth, Shai cites the great Archbishop William Temple (1881-1944), who stated: 'Humility does not mean thinking less of yourself than of other people, nor does it mean having a low opinion of your own gifts. It means freedom from thinking about yourself at all.'

Another misnomer is the prevalent view in many Christian quarters that Judaism doesn't have a notion of grace. The Hebrew for 'grace' is chen or chesed, both of which feature quite a lot in the Hebrew Bible. According to Shai, 'the gift of life is grace'. 'The existence of the world is not something that anyone earned. G-d's love for us is grace ... which we strive to live up to. And the revelation of Torah is grace – it is a divine gift given to us through no merit of our own.'

Shai coins the new term of 'possibilistic' rather than 'optimistic' to describe the Jewish approach to human nature. We can choose the good. Whether we 'will' do so is up to us. And if we fail once, twice, or many times, we can pick ourselves up and always try again.

Shai often cites the words of the greatest Jewish medieval thinker, Moses Maimonides, the Rambam (1135/8-1204): 'This reality as a whole – I mean, that G-d has brought it into being – is grace' (Guide of the Perplexed 3:53).

The English Bible translator, Myles Coverdale (1488-1569) was wondering how to translate the term 'chesed', and came up with 'loving kindness'. This was well before the appearance of the King James version of the Bible, which learned a great deal from Coverdale's translations.

Shai does however emphasize the differences between Judaism and Christianity. Christianity is not, as some have stated, 'Judaism without all the rules and regulations.' Of course theologically, Jews reject the Trinity and the incarnation, and also insist that the Messiah has not yet come. But even concerning love, there are differences between Judaism and Christianity. Jews, for instance, and as explained above, see law as a 'divine gift, a site where G-d's love and our own meet.' In Judaism there is no dichotomy between law and love. This idea of a dichotomy is 'antithetical to Judaism.'

In addition, Judaism is highly particularistic. Christianity highlights universal love. Jewish tradition is 'less ambivalent about the religious significance of family, friends and community'. 'Local loves are the stuff out of which broader, more universal commitments may emerge. For Jewish thought ... the path to universal love always runs through the particular.'

In my own view, this is why, despite everything, the State of Israel always appears within the top five of the world's happiness listings. Israel suffers from next to no instances of teenage self-harm, suicidal thoughts, binge eating, self-starvation or other afflictions of the western world. The sense of community demonstrated by Israelis is truly remarkable. And the birth rate is just under four children per family in all sectors of the country. This must be a prime example of 'possibilistic thinking' for the future.

In addition, when we thank G-d, we say 'Modeh ani', 'grateful I am'. The gratitude comes first and the ego is secondary. Not 'I think, therefore I am', but rather 'I thank, therefore I am'. By doing something to show gratitude, we put in motion 'the flowering of chesed'. We are 'made to give' and this flow of goodness is 'like a river.'

Gratitude does not however preclude the idea of 'protest'. According to Tanach (Hebrew Bible), protest is a 'mitzvah', a commandment from G-d which we can't shirk. Protest is a form of love. And some can actually find their faith through protest. We should not accept the world as it is, but strive to help build it as it ought to be, as 'sacred discontent.'

G-d, then, actually solicits protest. In Judaism 'docility is far from a religious ideal.' We see this from Genesis 18: 23-25, where Abraham argues with G-d about G-d's desire to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah. Abraham's argument with G-d is regarded as heroic, unlike Noah, who although 'good' in a conformist kind of way, does what he is told and doesn't think about rescuing more than simply his own family and animals.

According to Shai, we should not simply go with the flow and acquiesce in order to get along with people and have a nice life. As stated above, simply accepting the status quo has done no-one much good.

As my own hero, Abraham ibn Ezra (1089-1164) states in his Short Commentary to Exodus 22: 21-23, 'The legal status of the one who oppresses and of the one who witnesses the oppression but keeps quiet is the same.' Here, we are told not to oppress the stranger, as we ourselves were strangers in Egypt. Nor should we oppress the widow or the orphan. So relevant for the Pesach festival we are celebrating at present.

Shai makes the point that 'in Jewish ethics there is no such thing as an innocent bystander.' We certainly learned that in the Shoah, and also just now, when open taunting of and actual violence against Jews is prevalent in the cities of the Western world. At the same time the police, the forces of law and order, when they are not actually encouraging this behaviour, at 'best' stand idly by and do nothing.

As we see, Moses becomes the heir to Abraham when it comes to speaking out against oppression from a place of love. He objects to an Egyptian attacking a Jewish person, but also expects the Jewish people to 'groan, cry, plea and moan' before G-d will heed their cries and bring them out of Egypt to redemption in the Promised Land. The Jewish slaves 'had been so deeply submerged in exile that they did not even notice that they were in exile.' This is a very important point. Sometimes, if one is stuck in the mire, one doesn't always realise it and sinks in even further. 'Crying out' is not a sign of weakness, but actually 'a bold act of assertion', the first glimmer of resistance to one's plight.

And the point is that it is G-d, not Pharaoh, who is G-d. Pharoah, like so many later monarchs, may think that he is divine, but there is only one G-d, and He is the One and Only G-d. This is another radical difference between the former Jewish slaves and their Egyptian masters, the culture which nurtured them. It is not Jewishly acceptable to be a slave. We have to consciously take action with which to liberate ourselves. Only by liberating ourselves are we in a position to liberate others.

It is better to have a suffering religion in which we cry out to G-d than a sanitized religion in which we live in comfort and do nothing to help implant G-d's mission on earth. We should love the world so much that we must fight for it. Love therefore is not 'limp acquiescence in cultural norms that maintain an unjust status quo.' Love is not always 'nice' or 'civil'. In a world as broken as ours 'anger is sometimes the most loving response.'

Highly respected and admired Rabbi David Stav of Israel has recently said something similar regarding our present festival of Pesach, commemorating our gratitude for being brought by G-d out of Egypt, given the fact that a great many hostages, including two babies, remain in the hands of Hamas.

'It is impossible to celebrate this holiday [of Pesach] without calling out to the heavens that the captives should be taken out from the darkness in which they are being held in and into the light of freedom,' he said in the Times of Israel.

To sum up this first part of Shai Held's magnificent book then, with thoughts for Pesach and the Exodus story, it is G-d who brought us out of Egypt, but we also had to make the effort and much of this effort looks highly ritualistic. However, there is method to this apparent madness and the story has not yet been completely told – it is only the beginning.

For it is our own efforts in partnership with G-d that may lead us out of the morass in which we currently find ourselves into a Promised Land of even more possibilities. Protest, together with gratitude, that is the key. And we, the active readership, owe Rabbi Shai Held a debt of gratitude for finding the courage to write this unique book, Judaism is about Love.