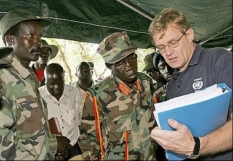

A senior commander in the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), which has terrorised Northern Uganda and surrounding countries for 20 years, gave himself up to American special forces. Dominic Ongwen has been accused of horrific actions and is to be sent to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague to face trial on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

A murderer who has enslaved children and been an accomplice to one of the most feared warlords of modern times, whose crimes include abductions, massacres, willful killing, rape, sexual enslavement, mutilation, maiming and child recruitment – surely Ongwen, if anyone, richly deserves his trial.

However, reports the IRIN news service, not everyone agrees. Retired Bishop Baker Ochola, a member of the Acholi Religious Peace Initiative (ALPI) – which has long campaigned for a negotiated rather than military or judicial resolution to the LRA crisis – said: "It's wrong and a bad thing to take him to ICC. The government of Uganda has no moral authority to support it.

"Even if he committed serious crimes against humanity, we as religious leaders stand for forgiveness. Even those who crucified Jesus on the cross, he prayed and forgave them because they didn't know what they were doing."

His argument is partly practical, as Ongwen's conviction could have implications for those still held by LRA leader Joseph Kony.

"The government should not jeopardise the lives of children and women still in LRA captivity," he says. "We appeal to the government to forgive and set him free. He should be given amnesty as any rebel who surrenders, renounces and abandons rebellion."

However, he also makes an ethical point.

"Kony who started the war should be the one tried. Not children who were abducted and forced to commit crimes against their will."

This is the heart of the problem of Dominic Ongwen, and many like him. Ongwen was captured by the LRA when he was only 10 and on his way to school, reportedly "too little to walk long distances". Caught at such an impressionable age, he grew up in the likeness of his captors, as many did; the LRA's practice of indoctrinating recruits by forcing them to mutilate and kill relatives or other children by bludgeoning them or biting them ensured that there would be no return to their previous lives. As the Invisible Children charity says, "Joseph Kony and his commanders brainwash abductees until, over time, these lies become indoctrinated as truth in the fighters' minds, thereby making the possibility of escape an unfathomable concept." Ongwen himself rose rapidly through the ranks, becoming a major at 18 and a brigadier in his late 20s. His relationship with Kony fractured, perhaps leading to his decision to turn himself in.

His story, however, indicates the difficulty of deciding the limits of responsibility when children are so thoroughly brainwashed that their sense of right and wrong appears to be entirely warped. Furthermore, the responsibility of individuals for even the most heinous of crimes has in this case to be seen in a particular context: the sense of grievance felt by the Acholi people of Northern Uganda, from which the LRA first originated, and its continuing sense that the child soldiers are still Acholi, no matter what they have done. The LRA did terrible things, but so, say the Acholi, has the Ugandan army; lopsided justice is no justice at all.

So, for instance, Okumu Reagan, the chair of the Acholi Parliamentary Group, told IRIN: "I think [the] international community needs to look at circumstances and scenarios surrounding Ongwen. That abducted children like Ongwen, who were forced and conscripted into the culture of killing, raping, mutilating, maiming, sexual enslavement and other crimes because of the failure by government to protect them, [now] face trial is an insult for humanity.

"Ongwen was abducted, indoctrinated and shaped into a killing machine against his will like other children still in LRA captivity."

Winnie Laker, a war victim in Kitgum, northern Uganda, says: "It's double standards by government. Why didn't it prosecute Kenneth Banya, Onen Kamundulu and Sam Kolo [senior LRA commanders who received amnesties following their capture or surrender] who too committed atrocities in the region? Ongwen should be forgiven and pardoned." Referring to the reconciliation process central to the culture of the Acholi community, she said: "We want him to undergo Mato Oput."

Others, however, are less forgiving. One LRA victim, James Odongo, is opposed to an amnesty.

"That guy [Ongwen] committed serious atrocities. He should be immediately transferred to The Hague to face justice. Our justice system in Uganda lacks integrity and already there are some voices calling for Ongwen to be pardoned and given amnesty.

"With the political [election] campaigns around the corner, you never know, [President Yoweri] Museveni may want to use it for political votes."

While Titus Obali, who spent just under a year in Ongwen's captivity before escaping, said: "Ongwen and his boys used killing, beating, maiming and raping as a weapon to inculcate and indoctrinate people into the LRA rebellion. He forced many children to kill people.

"I personally witnessed him kill people. He used an axe to hack one of the persons [rebels] who escaped from South Sudan with a gun. He chopped him by the neck. He called us to see. He told us if any of us tried to escape, the same would apply. We feared for our lives. They killed so many people.

"Since he has surrendered, let justice takes its course. If ICC wants me to give my testimony, I am ready to testify against him for the atrocities and crimes I witnessed him commit."

Child soldiers who have managed to escape or been liberated from the LRA face a desperately difficult time as they try to re-integrate with their society. Many are traumatised; many face fear and rejection because of what they have done. Josephine Inopayngba, 27, a counsellor in Dungu for former child soldiers and LRA abductees, told IRIN that the fear instilled by LRA methods remains. One escapee from the LRA made pregnant by rape "told me she wanted to kill her child at birth. I told her the child is innocent. She said kids kill their parents and she was afraid the child would grow up and kill her."

Charities such as Invisible Children have effective programmes aimed at encouraging former LRA members to come home and supporting them when they do – though the scale of the problem, because of the sheer numbers involved, is vast, and the region is still poverty-stricken because of corruption, neglect and misgovernment.

The Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, set up to help negotiate an end to the conflict and mitigate the military response of the Ugandan government – issued its annual end of year peace message in December. It spoke of the need to promote a culture of forgiveness and reconciliation, noting that army action against the LRA in 2008 had only driven it out of Uganda, causing "untold suffering" in the Central African Republic, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

It said that the spirit of unforgiveness had caused "the stigmatisation of those affected with HIV/AIDS, those born in the LRA's captivity and the girl-child-mothers who came back with children born in LRA captivity. Domestic violence still persists against women; inter-state hatred still exists as a result of the LRA war ... Land disputes and other community conflicts have become part of the definition of the contemporary life in Acholi Sub Region."

If Dominic Ongwen is send to the ICC for trial, it will be years before there is a result. In the meantime, Joseph Kony is at large and the troubles of the Acholi region are unresolved.

It is very tempting to think that a criminal has been caught, and to leave it there. However, the questions of personal, corporate and national responsibility go much deeper than that – and while the ICC might shed some light on these, it cannot provide answers.