How a 3,700 Babylonian clay tablet could hold the secret to exploring space

Australian scientists have decoded a 3,700-year-old Babylon clay tablet, revealing it as the world's oldest and most accurate trigonometric table.

The 'Plimpton322' tablet was discovered in the early 1900s in the ancient city of Larsa in what is now southern Iraq by by archaeologist, academic, diplomat and antiquities dealer Edgar Banks, on whom the fictional character Indiana Jones was based.

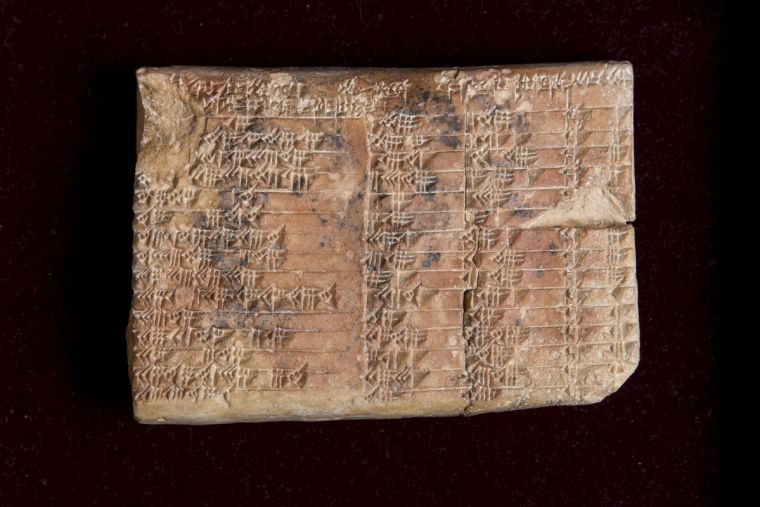

It has four columns and 15 rows of numbers written in cuneiform script. However, until now no one has been able to work out what it was used for.

'Plimpton 322 has puzzled mathematicians for more than 70 years, since it was realised it contains a special pattern of numbers called Pythagorean triples,' according to Dr Daniel Mansfield of the School of Mathematics and Statistics in the University of New South Wales Faculty of Science.

'The huge mystery, until now, was its purpose – why the ancient scribes carried out the complex task of generating and sorting the numbers on the tablet.'

Now, however, the mystery has been solved.

'Our research reveals that Plimpton 322 describes the shapes of right-angle triangles using a novel kind of trigonometry based on ratios, not angles and circles,' said Mansfield. 'It is a fascinating mathematical work that demonstrates undoubted genius.

'The tablet not only contains the world's oldest trigonometric table; it is also the only completely accurate trigonometric table, because of the very different Babylonian approach to arithmetic and geometry.'

The tablet was created in Larsa during the Old Babylonian period of 1900-1600 BC. The city was captured in 1762 BC by King Hammurabi, thought to be contemporary with the biblical patriarch Abraham. Hammurabi's law code is believed to have influenced the Mosaic laws in the Old Testament.

The new study by Mansfield and UNSW Associate Professor Norman Wildberger is published in Historia Mathematica, the official journal of the International Commission on the History of Mathematics.

Mansfield read about Plimpton 322 by chance and decided to study Babylonian mathematics after realising that it had parallels with the rational trigonometry of Wildberger's book Divine Proportions: Rational Trigonometry to Universal Geometry.

The Babylonians counted in base 60, unlike moderns who use base 10 or computer language that uses base 2. Base 60 allows much more accurate calculations to be made, as it uses whole numbers rather than approximations.

Wildberger said: 'It opens up new possibilities not just for modern mathematics research, but also for mathematics education. With Plimpton 322 we see a simpler, more accurate trigonometry that has clear advantages over our own.

'A treasure-trove of Babylonian tablets exists, but only a fraction of them have been studied yet. The mathematical world is only waking up to the fact that this ancient but very sophisticated mathematical culture has much to teach us.'

Mansfield said: 'If computers could be programmed to work in base 60 it might be possible to increase accuracy and decrease cost. This would be particularly beneficial for work requiring high accuracy, such as surveying, or scientific calculations, or where power is an issue, such as in space probes or where speed is an issue, such as in computer graphics.'