How the book of Leviticus teaches us how to be saints

'And called'.

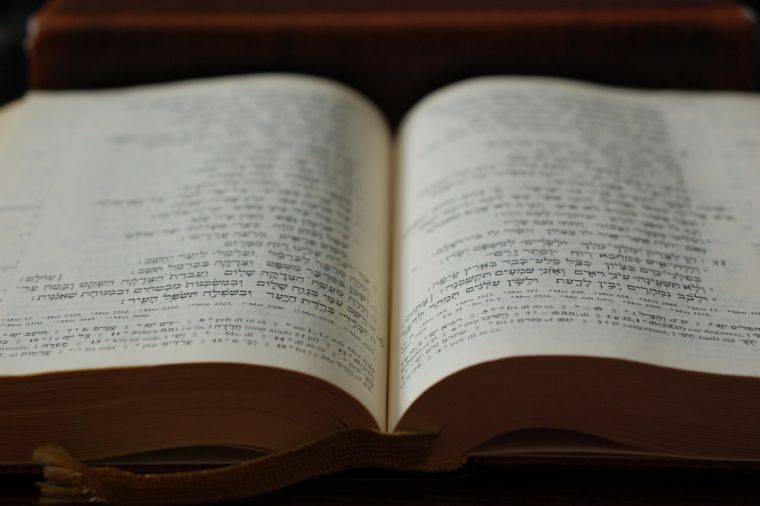

Rather than the version familiar in translations – 'The LORD called to Moses' – this is how the book known as Leviticus' begins in Hebrew: no subject of the calling and a small letter 'aleph' at the end.

What does this mean? It is a calling to Moses, a vocation, but with the normal letter 'aleph' written small at the end of the word 'calling'. This reminds Moses that humility is the key and that the later titled grandiosity of popes, patriarchs, archbishops, bishops and priests is a far cry from what is expected of us as Jews.

The Mishkan (G-d's indwelling, known in English as the Tabernacle) has been completed and now it is time to consider the nature of sacrifice. Various types of 'sin' are enumerated, the main point being that even small misdemeanours, slight errors of judgment, should be avoided if possible in our daily lives.

Leviticus, the third book of the Pentateuch, is the most misunderstood by people who aren't Jewish. Read mainly in translation, all its nuances are lost. Read without the biblical commentaries, one might as well be swimming in mud.

And yet, it is possibly the most important book of them all. Later we will read in the same book about loving your neighbour, but in a context of how exactly to go about doing this – the positives and the negatives.

Talking about neighbours, on Shabbat I was invited to a meal at the home of a midwife. I had only met her once, at a religious lecture (known as shiur) that we both attend during the week.

At the door I was greeted by her children as if I were a combination of favourite aunt and Father Christmas. She started talking to me in rapid modern Hebrew – the first time this has happened in 10 years – and the language immediately returned. We talked about the importance of midwives. She had trained in Holland, where more people give birth at home than at hospital, and I told her that I myself had opted for home-births both times round. She works at St Mary's in Manchester, where I was born, and which has the reputation of being the best hospital for childbirth in the city.

When the meal was finished, the children in bed and her husband at another celebration, we got down to serious talking.

'Tell me', she said, 'how do you define a saint?'

I am not one for avoiding questions and if I don't know the answer I ask other people or look it up. But as it happens, I do have views on what constitutes saintliness.

I couldn't tell her that I was looking straight at one, so said, 'We don't tend to go in for saints in Judaism. Because saints imply sinners and that simply isn't our type of religion. Our goal is to be a "mentsch", translated as the best human being you can be, warts and all.'

'It's my work', she said. 'All these people come in to be delivered with photos of saints to help them along.'

'Most, if not all the saints in history', I said, 'have hated us – from the church fathers, through the Middle Ages, and even some today. If it makes your clients feel better having photos of them stuffed in their pockets while they give birth, fair enough, but what the world thinks of as saintliness isn't always a good thing.

'What could be better', I continued, 'than having four lovely children, bringing forth the children of others into the world, preparing your home for Pesach and inviting guests for Friday night? This may not be saintliness as others see it, but it's good enough for me.'

And then we had the type of conversation that you only have once in a lifetime.

When I left, I marvelled at the fact that this midwife was nearly half my age, but had a poise and dependabiilty of someone twice her age.

The complementary reading to the beginning of the third book of the Bible, known in Hebrew as 'And called', is taken from the book of Isaiah (43:21-44:23):

'And now listen, Jacob thy servant and Israel whom I have chosen. So says the Lord your maker and fashioner from the womb – he will help you, fear not.'

The Lord makes and fashions us from the womb, the word for 'fashion' being 'yotzer', also meaning the two inclinations, for good and for evil, with which we are all born, together with the freedom to make our own choices.

We have the capacity for good and evil inside us when we emerge from the womb. There is no 'fall' in Judaism, simply a constant struggle between what is right and what isn't, and trying our best is all we can do.

And anyone who helps to deliver human beings into the world is part of G-d's plan to make the world better.

So whenever a midwife asks me to define a saint, I find it very difficult not to stare back and tell her that I am looking straight at her – the person par excellence working in the image of G-d, the creator of all.

Dr Irene Lancaster is a Jewish academic, author and translator who has established university courses on Jewish history, Jewish studies and the Hebrew Bible.