A thick layer of dust coats everything inside the Eritrean embassy in the Ethiopian capital, which was unlocked this week for the first time since 1998. Photos of this 'time capsule' were published by the BBC, which, along with the world's media, is charting the remarkable thaw in relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia. The two nations went to war in 1998 but maintained a war footing due to Ethiopia's refusal to allow demarcation of their common border, in accordance with a 2003 ruling.

Since coming to power in April, Ethiopia's new president, Abiy Ahmed, has embarked on a raft of reforms. The state of emergency was ended; the head of prison services was fired following allegations of widespread torture; thousands of political prisoners were released; proscribed organisations can now function and media restrictions were lifted.

President Abiy also prioritised peace with Eritrea. In a change in direction, he agreed to implement the UN-brokered agreement in full, including border demarcation. Things have moved swiftly: he visited Eritrea, peace was officially instituted, and Eritrea's President Isaias Afewerki made his own historic visit to Ethiopia, where he received gifts, attended a peace concert and raised the flag at the re-opened embassy alongside his counterpart. Meanwhile, the UN secretary general amongst others has mooted the prospect of lifting the sanctions imposed on Eritrea for destabilising Ethiopia and Somalia.

These welcome developments may assist in lowering tensions in the Horn of Africa and may also produce economic benefits. However, while the rapprochement was preceded by human rights improvements in Ethiopia, similar developments are yet to occur in Eritrea.

Eritrea's human rights record remains among the worst in the world. The government's seeming obsession with controlling every aspect of its citizens' lives and its heightened sensitivity to any perceived challenges mean the extensive rights enshrined within its ratified but unimplemented constitution have been disregarded.

Rights are comprehensively violated, including the right to freedom of religion or belief. A UN Commission of Inquiry has determined the regime and its officials have committed crimes against humanity since 1991, including the crime of persecution. Eritrea's Christian community has experienced severe repression since 2002, when the government effectively outlawed every religious community except those practising Sunni Islam, Orthodox Christianity, Catholicism, and Evangelical Lutheranism.

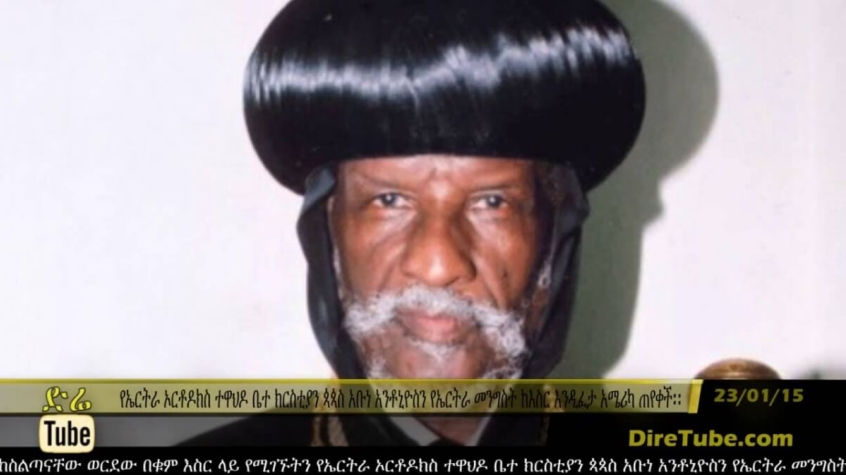

As he arrived in Ethiopia, President Afewerki was met by several dignitaries, including representatives of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, whom he greeted warmly. Yet members of the Eritrean Orthodox Church who remain loyal to the legitimate patriarch face mistreatment and imprisonment, while Church assets are regularly expropriated. On July 12, Patriarch Abune Antonios marked his 91st birthday under house arrest, which he has endured since 2007. One of many prisoners of conscience, his release and reinstatement would serve as a litmus test for genuine reform.

Even as President Afewerki basked in admiration in Ethiopia, tens of thousands of Eritreans were languishing in unsatisfactory detention facilities ranging from shipping containers to open air facilities in deserts. Among them are several hundred Christians from non-sanctioned churches, detained indefinitely in a campaign of arrests that has been ongoing since 2002, and which at its zenith saw around 3,000 detained arbitrarily.

Conditions are dire. According to eyewitnesses, prisoners of all faiths and none are deprived of adequate food and water and timely access to medication. The lack hygiene poses particular problems for female prisoners. All prisoners are also subject to severe mistreatment; however, female prisoners are vulnerable to gender-based violence.

Conditions are also life-threatening. In August 2017, Fikadu Debesay, a Christian mother-of-four detained in house-to-house raids in Adi Quala in May 2017 and held in a desert camp, died on her way to hospital following mistreatment, poor conditions and delayed medical assistance. Her husband and eldest son, who had also been detained, only found out about her death when they were released weeks later.

Children are not spared. In May 2016, 79 men, women and children, including a mother and baby, were rounded up during a wedding party. In August 2016, eight Christians, including a mother and her three year-old child, were arrested while gathering in a rural area.

Even when they are not arrested with their parents, children still suffer. In May 2017, 45 Christians were arrested during raids in Adi Quala including entire families, the elderly and a disabled woman, leaving 23 children without parental care. Thirty-three women who were among the first to be arrested in the raids in May were detained in an infamous island prison. Most were young mothers whose husbands were either military conscripts or were eking out existences elsewhere. Their arrests deprived 50 children of parental care.

Thousands flee Eritrea each month, risking a shoot-to-kill border practice and abuse by traffickers. Figures from the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) illustrate that by the end of 2015, around 12 per cent of the entire population had fled. According to the organisation's March 2018 report, 167,969 Eritreans have sought refuge in Ethiopia, with 2,772 arriving from January to March. Seeing the author and embodiment of the abuses from which they fled being feted in the country where they sought refuge must be deeply worrying for this vulnerable community.

Eritrea used the conflict with Ethiopia to justify its militarised society, the perpetual war footing, indefinite military service, civilian militia duties even for the elderly and clergy, and the indefinite deferral of democratisation. Since peace is now official, demobilising the civilian militia and conscripts, and facilitating fundamental rights and freedoms would constitute additional evidence of genuine change.

The international community must resist the urge to take Eritrea at face value. While the current rapprochement is to be encouraged, true peace must include justice for Eritreans. Human rights monitoring remains more important than ever, as the regime's greatest victims are still its own people.

Dr Khataza Gondwe is Christian Solidarity Worldwide's joint head of advocacy and team leader for Africa and the Middle East.