Tears of Gold – portraits of the persecuted

Artist and human rights activist Hannah Rose Thomas has travelled the world leading trauma-healing art workshops with women affected by war. Her debut art book Tears of Gold presents her portraits of women in conflict zones who have survived war and sexual violence. Her moving portraits have been acknowledged by King Charles III, who wrote the foreword to the book.

Christian Today spoke with her on International Women's Day at the Tears of Gold exhibition in London to hear about her motivation behind the book, the impact her art workshops have had on victims of violence and conflict, and how her faith has been encouraged through her work.

What spurred you on to produce Tears of Gold?

When I lived in Jordan as an Arabic student in 2014, I had an opportunity to organise art projects with Syrian refugees for the UN Refugee Agency – an experience which opened my eyes to the magnitude of the refugee crisis confronting our world today.

I began to paint the portraits of some of the refugees I had met, to show the people behind the global crisis, whose personal stories are otherwise often shrouded by statistics. My experience in Jordan also opened my eyes to the healing power of the arts and its potential as a tool for advocacy. I am aware that what I have been involved with thus far is but a glimpse of the potential healing and restorative power of the arts as a catalyst for change.

Please share a bit about the work you did with Open Doors in Nigeria.

Through the support of Open Doors, I had the privilege of facilitating trauma-healing art workshops. In northern Nigeria. I taught the women how to paint their self-portraits as a way to share their stories. Many of the women chose to paint themselves with glistening tears of gold: this inspired the title of the book. One young women Aisha, who had suffered rape at the hands of Fulani militants, said that the gold tears symbolised God bestowing on her a crown of beauty instead of ashes; the oil of joy instead of mourning (Isaiah 61:3).

What responses have you had to your trauma-healing art workshops?

The hope was that these art projects would create a space that honours the experience and the women's stories, and for each person to feel seen and heard. This is especially important given the stigma, shame and silence surrounding issues such as sexual violence. The arts can help by giving a new form of communication to address the silence and unspeakable pain. Feelings are communicated through drawing and painting that perhaps cannot be expressed through words.

Is there a survivor's story that has stuck with you?

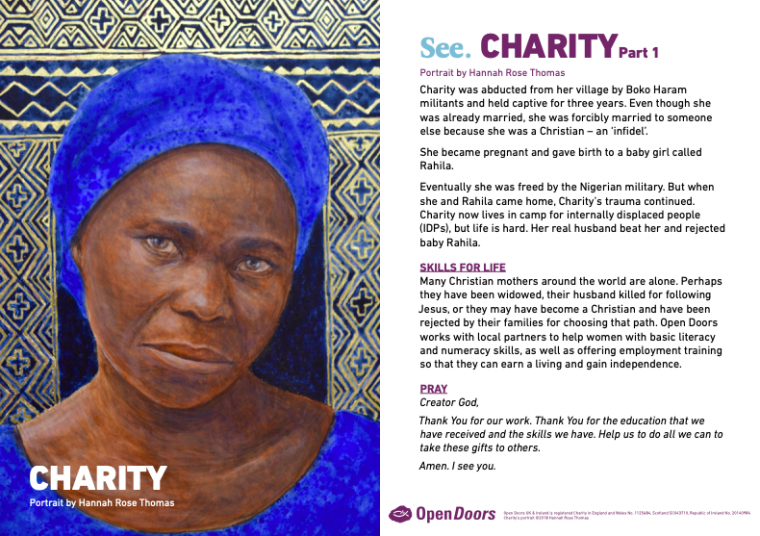

In northern Nigeria, one woman who took part in the art workshop, called Charity, had been kidnapped by Boko Haram and held captive for three years. [After being freed by the Nigerian military] Charity said, "I can recount three different times that I was beaten by my husband because I came back with a child. I have told him 'I haven't done it out of my own will. I was forced and there was nothing I could do."

She faces daily rejection and isolation in the Internally Displaced Persons camp in northern Nigeria due to the stigma surrounding sexual violence. On our last day together for the art project Charity said, "I am so happy. I have never held a pencil in my life before, and this is the first time I have been able to write my name and even to draw my face!"

What do you think the Church can do to support women in conflict zones?

Conflict leaves many wounds, but perhaps the most significant of all is the invisible stigma that so many survivors of sexual violence face. The perceived association of survivors and their children born of war-time rape with the enemy compounds the pain, shame, isolation and trauma. I witnessed this in northern Nigeria, which was heartbreaking to see. The Church can do more to support, welcome, honour and value women who have endured conflict-related sexual violence. This will help to counteract the stigma and shame and thereby enable healing within the communities who have suffered such violence.

What is the process behind your paintings? Do you meet with the women beforehand to have a discussion?

The way I love to work the most is spending time with the women doing the art workshops, in Iraq and northern Nigeria. It was only through that time that the woman would share their stories if they wanted to. It was after that time of sharing their stories I would then ask if they were still happy to be painted. I would take photos of them after they would share their stories to paint from and I did these paintings after I returned home. I use very time consuming early renaissance painting methods and find it's a form of prayer using these painting techniques. It's a time where I'm thinking about each of the women and their stories while I paint and I hold them in my heart and pray for them while I paint.

As you were painting the women, what went through your mind?

Often tears would come to my eyes as I remembered their stories and what they've been through, but also the certainty of the situation they were still in. I was returning home to safety but they were in refugee camps in northern Nigeria and Iraqi Kurdistan and these other contexts. The memory of each woman and their stories was so vivid in my mind. They are just emblazoned in my heart and my memory. I think of the paintings as being a form of lament and grief for these women.

How has your faith been encouraged through the work that you do?

I have been changed in so many ways by these women that I have met. I feel like it truly has been the greatest privilege to meet them and to have been entrusted to share their stories and portraits and also their extraordinary faith as well. In northern Nigeria the women I worked with through Open Doors came from Christian backgrounds and they had such faith in God's goodness. They showed such kindness, grace and joy, it was infectious. I came away remembering what Jesus says, that the first will be last and the last will be first into heaven. I think that these women wanted to be painted in a way that almost seemed regal. They may be forgotten on earth or they might not be well known on earth, but in spite of what they have suffered they will be the most honoured women in heaven. That was something I wanted to capture through these paintings.

What do you hope people will gain from the book?

Through my portrait paintings I seek to convey that each of us are created in the image of God and equally valuable in His eyes, regardless of race, religion or gender. The arts affirm the language of empathy – they can provide us with a language for mediating the broken relational and cultural divides.