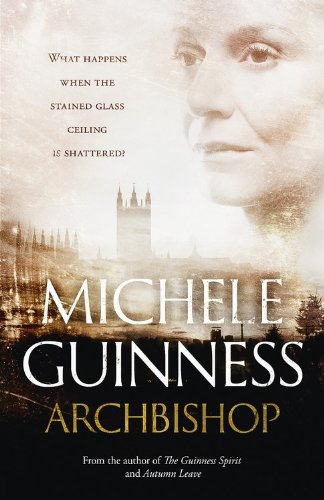

Two perspectives on Michele Guinness's new book Archbishop

Michael Trimmer:

Thanks to the recent General Synod votes, women bishops may only be a few months away for the Church of England.

In 'Archbishop', the year is 2019 and the previous Archbishop of Canterbury is found dead in a hotel room, with women's underwear in his hand that didn't belong to his wife.

After a prologue featuring some well-drawn negotiations between various senior figures of the Church of England, we are launched into the life of the first woman to hold the office of Archbishop of Canterbury.

The central story's main character is Victoria Burnham-Woods who hails from a middle class background, is privately educated, and the daughter of a a teacher and traditional tailor.

She is something of a champagne socialist, deeply concerned about the problems of the poor despite her own comfortable upbringing. Her social conscience is present in almost every circumstance, even in some of the most intimate moments of the novel.

Yet she is also very much a traditionalist when it comes to that most contentious of modern church issues, gay marriage. Even in the face of a gay prime minister, she remains faithful to the traditional Anglican position on the incompatibility of homosexuality and matrimony.

In this respect, she represents what many Christians aspire to be, a blend of deep compassion and conviction. Caring for all while not compromising on what the Bible says is true.

However, as a character in a novel, a reader may find their level of interest in her waxes and wanes.

Ms Guinness has structured her novel in a peculiar way, with almost every chapter containing a segment of story from Archbishop Burnham-Wood's past, which tells us more about her and gives the reader insight into the background of the situations as they play out in the 'present'.

But many readers may find themselves wishing they could cut through these parts to get on with the 'present', where Ms Burnham-Woods is actually Archbishop of Canterbury.

Too often it seemed as though the book was less a novel, and more a novelised autobiography of a fictional person. This in itself wouldn't be so bad, except we see so little of the main character's 'present' exploits, between many of the flashback sections.

Consequently, a reader might find themselves not caring enough about Ms Burnham-Woods to want to hear more and more of her backstory. If this kind of information had been revealed as the novel went along, that would be a different matter, and would have made for an overall smoother read.

Like any good depiction of life in a modern day leadership position, there isn't just one central story. In this respect, the book is reminiscent of "The West Wing" television series, with multiple ongoing threads of all the different issues a leader will have to deal with, against a backdrop of overarching plot elements.

For the Archbishop, the hot button issue of the day is an anti-proselytising bill, supported by a PM unhappy that the Church of England is so unwilling to tow the government line on equality.

In the story, this bill is ostensibly put in place to limit the powers of those who would try and radicalise Muslims in the UK, but to avoid cries of discrimination and racism, it is applied more universally to all religions, Christians especially.

On the one hand, given various anti-Christian rulings in many courts across the UK, the government moving in this direction is not so far-fetched. In the real UK of today, pastors have been arrested for street preaching on certain issues, and there are examples of Christians being marginalised for talking about their faith in the workplace. Ms Guinness does paint a rather bleak picture of the future of religious freedom in Britain but amid politically motivated lawsuits and general anti-Christian sentiment, this aspect of the plot is easy to imagine.

The central thread running throughout the novel is a conspiracy to unseat Ms Burnham-Woods and get "the right man for the job" back to Lambeth Palace in her place.

Ms Guinness has said in an interview that conspiratorial politics are in fact a sad reality of life in the Church of England. It's clear that conspiracy elements of the plot have been exaggerated and expanded for dramatic effect, but in doing so against the background of an otherwise realistic and believable novel, the boundary of the farcical feels a little pushed.

It's not that we couldn't believe that there are conspiracies in the Church of England, it's the level to which the characters in the book go in these efforts. Anonymous, vaguely threatening phone calls are one thing; electronic surveillance is something else.

That said, many of the incidents that Archbishop Burnham-Woods faces down - the difficulty of holding together a fractious global Church, the stress of a marriage where one party lives in the public eye, the challenges of unexpected debilitating health issues - are handled excellently.

Of particular interest is Tom, the Archbishop's husband, who becomes the focus of a wave of negative media attention. It is fascinating to see the husband of a leader treated in this way, and something for men to reflect on as they watch the media tear into the women behind so many of the world's powerful male leaders.

Overall, this book could have taken some lessons from the work of West Wing show-runner Aaron Sorkin. While occasionally President Josiah Bartlett will have to deal with Middle East Peace, wars in central Asia, or hurricanes ripping through America's heartland states, most of the time he's got farm subsidies, trade regulations, and petty Washington pork-barrel politics to be dealing with.

That is the truly great challenge of a writer trying to write a story set in the corridors of power. The challenge of taking the mundane, which swallows up most of the days, even in the White House, and turn them into a dramatic story that keeps you reading. Ms Guiness does indeed keep you reading with her gripping tales of intrigue and infighting, but are they really what the Archbishop of Canterbury has to deal with?

In that respect, this novel is a large failing to the many women who might want to know what the Archbishop's life is really like, the kinds of challenges and stresses of day to day life when your new home is Lambeth Palace, and how that would be different for a woman facing that role, compared to the continual stream of men living there in the past.

Rather than being given a realistic and somewhat gritty portrayal of executive Anglican life, we find ourselves presented with a vaguely watered down Dan Brown style story, where we're expected to believe that Church of England bishops and their associates go around bugging their colleagues' computers to bring each other down.

With so many ideas crammed in, a gay prime minister, anti-proselytising laws, health problems, dodgy business deals, media attacks, and conspiratorial insiders the overall story loses focus. We end up with a blunderbuss narrative, far less concerned with what it will actually be like for the first female Archbishop, and more worried about how the characters are going to get themselves out of this chapter's latest scrape.

This is a book that many will want to read, and many might enjoy if they're looking for a different kind of conspiracy novel. But many more will be disappointed as it misses a golden opportunity to give a real insight into what the Anglican Communion's highest office will really be like for a woman.

As a social commentary and picture of the Church of England, it is somewhat interesting, but your enjoyment of it as a novel will probably depend on which you're more engaged by.

Claire Musters:

This is significant book at a significant time.

That's what I thought when I picked up the huge volume that is Michele Guinness' first novel, 'Archbishop'. I was also slightly nervous. Would I like it? I knew that I don't hold entirely the same theological views as Michele, so I wasn't sure what I would make of the book – or the subject matter.

But I was gripped right from the first page. Being party to the discussions and negotiations surrounding the choosing of the next archbishop grabbed my attention and made it feel like I'd been allowed to enter a world that so few get to see.

The book sets the scene well, and showed the level of outrage at the idea of allowing a woman into such a prominent position of 'power'. Then Michele began to use the flashback narrative device to give us insights into the journey that Vicky Burnham-Woods had made to get to that point.

I wasn't sure about the flashbacks to begin with, as I was keen to hear about how Vicky would tackle her new job, but actually I found they worked well (until my mind got a little tired towards the end as I began to forget who some of the large number of characters were).

It was the flashbacks that contained the details necessary to reveal that, although the negotiation process had shown she wasn't necessarily the commissions' first choice, Vicky got there on her own merit. Having had to fight against the prejudice of the male majority as she was training and, indeed, as she climbed the CofE promotional ladder, Vicky proved time and time again to have the robustness and strength of purpose to make it at the very top.

I loved the fact that Vicky is an extremely strong character – and yet Michele also gives us glimpses of her vulnerability. There are instances that show her uniquely female approach to everyday matters too, such as when she struggles to decide what she should wear to various events (including her own enthronement). And how she sets to work quickly to make the study in Lambeth Palace more homely to enable her to work in it. Vicky also makes some immediate changes to the daily routine of the staff there, which does not go down well with the Chief of Staff – including moving morning prayer from 7am to 8am:

"'Archbishop,' he said, as if explaining the rules to a child, 'we have a way of doing things here, based on what we know works best…'

"Vicky resisted the urge to snap, 'My predecessor had no hair and didn't wear make-up.'"

It is these glimpses of the world through Vicky's eyes that I enjoyed the most, as they revealed the inevitable struggle and impossibility of fitting into the mould already created by so many men who had walked the corridors of ecclesiastical power before her.

There are little touches that will resonate most with female readers, as we are all too aware of how we are so often judged by our appearance. In the following extract Vicky ponders how her role is affecting her looks too, and how she feels about that: "She noticed newish furrows around the mouth, pouches of darkened flesh beneath the eyes, a slackness of the jaw that hadn't been there when she last looked. How time wreaked havoc with the human face. Mother Teresa had said that in their twenties, people have the beauty they're blessed with. At seventy-five, their faces are what they put into them. And there was beauty in every crease and furrow of the nun's lived-in, craggy face. Oh to grow old with a serenity like that."

I was also fascinated by the relationship between Vicky and Her Majesty. It was really interesting to see Michele's ideas on how the Queen may respond more warmly to a female archbishop, enjoying the solidarity of another female to work with.

I think it was a touch of genius to show how uncomfortable Vicky's husband Tom was with her new role, and the difficulty between trying to be supportive while at the same time be his own 'man'. Such must be the same struggles for wives of bishops and archbishops and yet watching how Vicky and Tom manoeuvre within their marriage and workplaces emphasises this more because it is Tom who is on the receiving end of the media's scrutiny as the archbishop's spouse. Throughout the book, Vicky, too, feels the pressure that her unique 'calling' has on her family. She is acutely aware of how they must be being affected and feels the tension deeply within herself.

I haven't regularly attended a traditional church since my young childhood, so I was glad to hear from other reviewers with such a background that Michele does a great job of telling the history and the 'behind-the-scenes' world of the Church of England. And I did find that aspect of the novel incredibly fascinating.

I also thought Michele handled really well some of the issues that church and state are grappling with today, such as same-sex marriage, freedom of speech, rising poverty and how much the government may rely on churches to provide services to their local communities. She pushed them further, perhaps painting a rather depressing picture, but all the while grappling with how such developments would affect the church as well as society as a whole.

I know Michele has been criticised for making Vicky a traditionalist who is against same-sex marriage, but I found it refreshing that she created a character who was willing to stand up for traditional values in the face of huge opposition from a gay prime minister. That, in itself, was a fascinating sub-plot.

There is an undercurrent of political intrigue and 'dark forces', as Michele describes them in my interview with her, throughout the book. I wondered if the conspiracy plot had gone a bit too far at one stage (and asked her about that), but, in all honestly, I was so totally engrossed by that point that I wanted to see it played out to the end.

The book is immense and covers some huge themes. While you may not agree with Michele's treatment of them all, I think 'Archbishop' is a brilliant insight into what life could be like for Britain's first female archbishop. I wonder how long it will be before the actual first female archbishop's memoirs are written…