'O love that wilt not let me go': How a blind pastor produced a work of genius

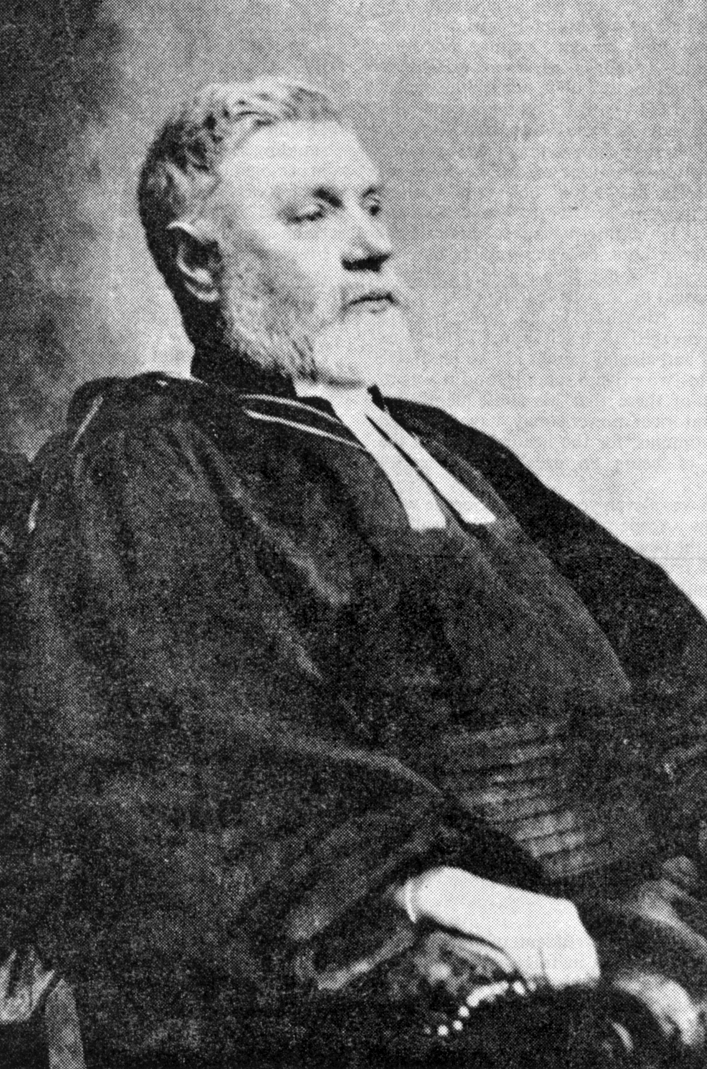

Today's the birthday of the author of one of the best-loved hymns in the English language. O love that wilt not let me go was written by George Matheson (1842-1906), and its powerful meditation on the power of God in the life of the believer never fail to move.

Matheson was a Church of Scotland pastor who went blind at an early age. However, he was a considerable scholar, thanks in part to the care of his elder sister, who read to him, and his own astonishing memory – he could quote whole passages of scripture by heart, and many of his hearers did not realise he was blind.

It is rare that we know the date of a hymn so exactly, but he has left us a record.

'My hymn was composed in the manse of Innelan [Argyleshire, Scotland] on the evening of the 6th of June, 1882, when I was 40 years of age,' he says. 'I was alone in the manse at that time. It was the night of my sister's marriage, and the rest of the family were staying overnight in Glasgow.

'Something happened to me, which was known only to myself, and which caused me the most severe mental suffering. The hymn was the fruit of that suffering.

'It was the quickest bit of work I ever did in my life. I had the impression of having it dictated to me by some inward voice rather than of working it out myself. I am quite sure that the whole work was completed in five minutes, and equally sure that it never received at my hands any retouching or correction. I have no natural gift of rhythm. All the other verses I have ever written are manufactured articles; this came like a dayspring from on high.'

There has always been speculation about the occasion of the hymn. One suggestion is that a fiancée broke their engagement when she learned that he was going blind. There is more romance than reality about this, though, because Matheson was almost completely blind from the age of about 20. We shall probably never know.

In the hymn, he writes of the love that will not let us go, the light that follows all our way, the joy that seeks us through pain, and – most movingly of all – the 'Cross that liftest up my head'. That line refers to Christ being lifted up in crucifixion, and perhaps what follows, 'I dare not ask to fly from thee,' reflect his own acceptance of the limitations he suffered. Nevertheless, it ends, 'I lay in dust life's glory dead,/ And from the ground there blossoms red/ Life that shall endless be.'

Whatever the trial which gave rise to the hymn, this note of faith was typical of him. He once wrote of his life that it was 'an obstructed life, a circumscribed life ... but a life of quenchless hopefulness, a life which has beaten persistently against the cage of circumstance, and which even at the time of abandoned work has said not "Good night" but "Good morning."'