How God's gift of a horse helped a Christian woman through the hardest year of her life

It's something of a rural fantasy, straight out of Downton Abbey or Pride and Prejudice. You're riding on horseback through an ancient English woodland in the early morning, the bluebells are opening around you and you're breathing great lungfuls of unpolluted air. It's pure luxury, and most of us envisage the scene with a touch of wish-it-was-me envy.

Things aren't always what they seem, however. On a spring morning near Winchester in Hampshire, the rider might have been Hazel Southam. And her horse Duke is what's helping her survive the hardest year of her life.

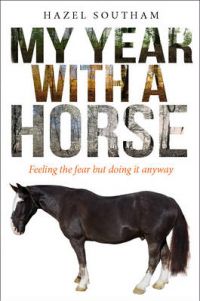

She tells the story in her book My Year with a Horse (Lion, £8.99). However, though her relationship with Duke frames the narrative, at its core is her struggle to cope with her father's dementia – a struggle made even harder by her mother's stroke and her own dangerous illness.

A successful journalist, Hazel had known for a long time that her father's mental capacity was inexorably declining. A difficult Christmas ("he was lost and scared, depressed by something he couldn't fathom and angry at a diagnosis that he utterly refuted") was followed by a determination to take on a new challenge.

She has, she says, "a dreadful habit of looking things that terrify me in the eye and taking them on". In her professional life as a journalist it's a characteristic that's taken her cheerfully to war zones. But now, terrified of horses from an early age in spite of her rural upbringing, she signed up for riding lessons.

Duke was huge, a 118-stone draught horse. But he was gentle and docile, and with help from her friends at the Hampshire Riding Therapy Centre she became a competent rider. She writes of beautiful experiences in the Hampshire countryside, rides with friends and instructors, and of the slow process of getting to know the horse and how he thought. She's honest about the fear, too.

She writes at one point: "There are days when I know deep in my soul that I am not a horse rider... What I fear is not necessarily what Duke will do in any given circumstance, but how I will react. I will freeze with fear." On days like this, "I get myself into such a near-death tizzy that I will not allow myself to ride, and I simply groom Duke instead. No one at the yard understands this. They may sympathise, but they think I'm crazy. They all want to ride all day and every day. I have to summon every fibre of my being to do it."

But alongside this a deep, trusting relationship develops. And, says Hazel, "a relationship with a horse is like relationship with a person. They have a personality. There are points of disagreement; I had to learn to speak his language, not impose mine. He was the person you hope everyone will be – trustworthy, kind, professional."

And it's this relationship that carried her through her worst year. She knew her father – a highly intelligent, articulate man who had a Europe-wide reputation as a botanist – was deteriorating. But things came to a head when she was about to go into work at Bible Society. He'd called her repeatedly on her way in, and when she returned his call all he could say was that there was something wrong with her mother. It turned out she'd had a stroke. Hazel "broke the land speed record on the M4" back to their house, only to find that her mother had been taken to hospital and her father had driven off to buy some bacon.

It was this incident that convinced her they needed help. She tells Christian Today: "There comes a crisis point where everything changes. To recover, my father had to go into care. It was a fork in the road."

While her mother recovered in hospital, Hazel realised they couldn't care for her father at home any longer. She writes of their struggles with officialdom and the trauma of having to make him do what he didn't want to do. "It felt like I was running from the battle. It wasn't good," she says.

Her father's illness is threaded through the book. But there are other burdens to bear, too. She needs to earn a living as a freelance writer, and a writing assignment takes her to Ethiopia. It's a tough assignment anyway. Then there's a car crash. But worst of all, she contracts both West Nile virus and Dengue fever. After a period of desperate illness she recovers, but she's told she can't risk travelling abroad again anywhere those diseases are present. It was, she believed, the end of her career as she'd known it.

Where in all this was Duke? Reflecting on it later, she acknowledges that facing her fear of horses, learning to control a giant animal with voice, hands and body, was a way of facing other fears as well. She tells me: "I wasn't aware of it at the time, but I was looking at a lot of fears at the same time. During that year I was obsessed by what was happening to my family – it was out of control. I was living in fear all the time.

"Finding something I could control was really helping."

She instances a moment when she masters a particular type of trot. "I was so thrilled. I had achieved something in the midst of a whole sea of stuff I couldn't choose."

She recalls beautiful moments, like an early morning ride with a companion when a barn owl swoops across their path: "It was a gift from Duke, and I wouldn't have had it otherwise."

And where was God?

"There's not a nice, simple answer," she says. "Dementia is all grim. Every day is a different grim. The Psalms were a good place to go. Church – I'd go to church and cry. I couldn't pray coherently, I couldn't even think coherently."

But, she says: "I was reminded of the everlastingness of God's perspective when I was in the woods. They've been there for 800 years or longer. That's where I communed with God in a wordless fashion; I knew he was there because I could feel it."

There are no really happy endings with dementia. Hazel's father died, having deteriorated to the point where he no longer really knew her. Her mother is well, but in a postscript to the book we learn that Duke died too. But, she says: "They're both fine. Grief is the thing we feel, it's the corollary of love. If I hadn't loved Dad, I wouldn't have found it so painful. If I hadn't loved Duke, I wouldn't have cried like a child when he died. But they are in the presence of God, because God loves them even more than I do."

And she wants to tell people what she's learned. "I'm not suggesting everyone goes horse riding. But I hope they're encouraged by the reminder that other people have gone through hard years. You can feel so alone.

"Second, there is light at the end of the turnnel, even if it's very long tunnel. And anything is possible with love – with friends who love you and whom you love, you can survive remarkable amounts of very difficult times. I had Duke and loved him, and he loved me."