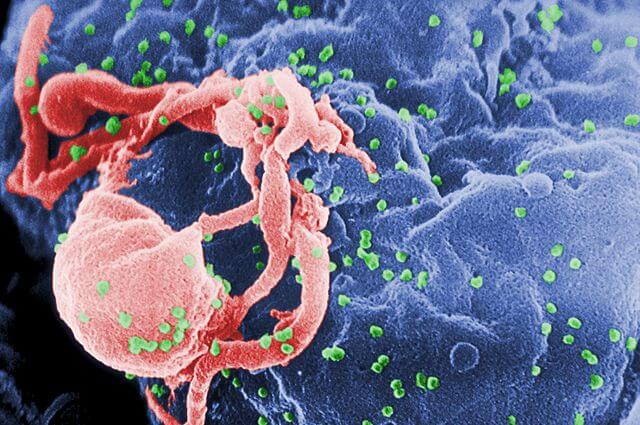

HIV cure update: HIV studies on female reproductive tract shows importance of ART

A new study looking at how the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) affects the female reproductive tract may help provide a better understanding on the importance of taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) seriously.

The study conducted by researchers from the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation last Tuesday.

Researchers found that giving ART can affect how the virus establishes an infection in the female vaginal tract. These findings can help support studies involving HIV prevention, cure, and vaccine development.

"Surprisingly, it does not matter how a woman is exposed to HIV — vaginally, rectally, etc. — the virus goes very quickly to the female reproductive tract," explained J. Victor Garcia, PhD, study co-author and a medicine professor, in a report from Science Daily.

Garcia went on to say that the CD4 T cells in the body, the cells targeted by HIV, can also travel to the female reproductive tract following exposure. "It is like putting more kindling on a smoldering fire," he said.

Using animal models, Garcia and colleagues discovered that the infection-fighting CD8 T cells take time to reach the site of infection, offering little protection. This delay will help the virus establish itself not only in the reproductive tract but also in "cervicovaginal secretions."

However, when ART is routinely given, virus transmission becomes less likely.

"Once ART was introduced into our models, the number of infected cells in the female reproductive tract and cervicovaginal secretions vastly decreased," Angela Wahl, PhD, study co-author, said in the report.

Despite giving ART, it doesn't mean that the virus is completely eradicated. Wahl explained that there will still be residual virus in the site, but only in levels that are not enough for the infection to spread.

"Collectively, our results ... may have important implications for the design of effective HIV prevention and curative approaches," the researchers concluded in their study.