Bishop Blames Violent And Punitive Theology For Alleged Abuse By Man Who Ran Christian Summer Camps

A senior Church of England bishop has stated that people who attended John Smyth's summer camps would have known each other and talked about allegations of abuse.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, a dormitory officer at the camps in the late 1970s, has insisted he was not part of the inner circle of friends and no-one discussed any allegations of abuse with him.

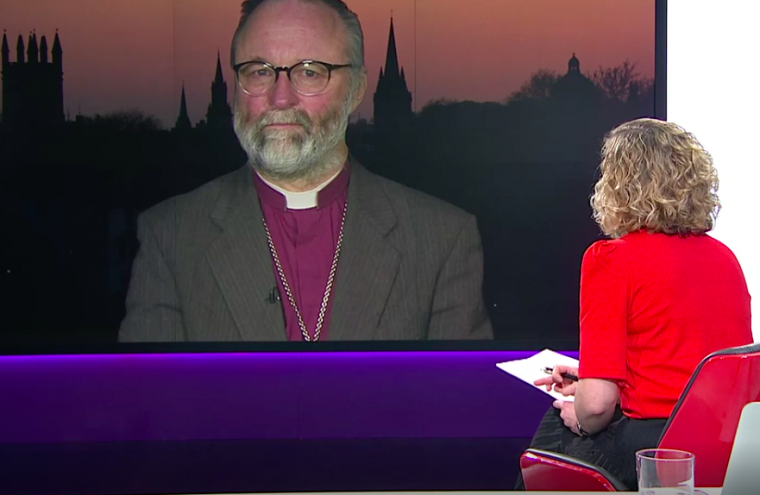

Bishop of Buckingham Alan Wilson was speaking out after police launched an investigation into claims that teenage boys from Britain's leading public schools were violently beaten, in what's been described as a "sadomasochistic cult" run by a lawyer with links to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Iwerne or "Bash" Christian summer camps were run by John Smyth QC, now a morality campaigner in South Africa.

Allegations of abuse that took place elsewhere, not at the camps themselves, have been subject of a series of investigative reports by Channel 4 News this week.

One victim, Mark Stibbe, attacked the Bishop for his statement about the theology behind the allegations.

He tweeted that Bishop Wilson was treating victims like a "theological test case" rather than people:

Bishop Alan Wilson treating us victims like a theological test case at seminary not people. Epic fail @cathynewman @Channel4News #livid

— Mark Stibbe (@markstibbe) February 3, 2017

Speaking to Cathy Newman of Channel 4 News, Bishop Wilson said Archbishop Justin Welby has said all he can about the camps.

Wilson said: "He was very young when all this happened. But the aspect, the thing I find really much more disturbing, is not so much about the Archbishop personally.

"These camps and this man's [Smyth] activities had extraordinary influence among senior evangelicals in the Church of England of my generation. Pretty much everybody who was anybody in the leadership of public school Anglican evangelicalism had something to do with John Smyth's operation.

"And I think that raises all sorts of disturbing questions. But I think the Archbishop's said what he can personally about it. I accept that. But I think the bigger question is what lies behind it really about the mentality of these people who have been immensely influential in the Church of England."

A 1982 report commissioned by the trust that ran the camps sets out in graphic detail the allegations of abuse. Not until 2013 was Welby made aware of it and the police finally involved.

Wilson said: "On one level I find it extraordinary because the [alleged] offences we are talking about were not some arcane kind of sex offence. Offences against the person act would cover them. If they happened they were certainly criminal by any standard really of decency.

"But of course the theology that these people bring to the table very often has an element of violence and sort of nastiness in it, a kind of element of punitive behaviour. God is seen as this punitive figure who is somehow out to 'get' people and I suppose it does blind people to what's going on in front of them sometimes, when there is that kind of violent basic theology."

He referred to a House of Bishops report a few years ago on domestic violence, that included an essay on harmful theology that blinds people to what's in front of their eyes.

Wilson continued: "I think this particular thing which was all about an obsession with sex and masturbation, it's all about sexualising relationships with young people through violence."

He said he had worked very hard with young people in the Church, with survivors who are coming forward and find it difficult to deal with bishops, and that bishops needed to reach out to these people.

But there were also lessons to be learned in terms of gay equality.

"Why can't the Church of England talk in a grown-up way about sex?" he asked.

There are no allegations of physical abuse having taken place at Smyth's summer camps, and no allegations of sexual abuse at all.

Newman asked Bishop Wilson if it was credible that Welby did not hear about the allegations until 2013, as the 1982 report into the claims was done by Mark Ruston, of the Round Church in Cambridge, a good friend of the Archbishop with whom he lodged during the late '70s in his final year at university. A second friend of the Archbishop, David Fletcher, also a clergyman, was the Iwerne trustee who led the investigation into the allegations.

Wilson said: "When you are young you accept things from people you look up to and admire. All of us do that.

"The theological blind spot is the most extraordinary bit of this. I'm sure he acted in good faith by the standards of the day and the way that he was at the time. That kind of close behaviour between people who were involved with these camps - I'm sure they knew one another and I'm absolutely sure they talked about it.

"But what is extraordinary is that nobody said, 'This is at the very least common assault if not ABH (actual bodily harm) and something should be done about it. And actually I'm still amazed that nothing has been done about this, this man is freely travelling around. It seems to be most extraordinary that nothing has been done.

"I think he should be brought to justice. Anyone watching these reports will feel that criminal offences have been committed against vulnerable people. And that it's in everybody's interests that the perpetrators should be brought to justice and receive a fair trial and that there should be a response to what they've done."

He was speaking out after it was revealed also that Smyth, once described by Welby as "charming and delightful", has faced police charges of killing a teenager in Zimbabwe.

Guide Nyacharu was found dead in a swimming pool at a camp run by Smyth in Zimbabwe.

Smyth, now 75 and living in South Africa where he campaigns on morality, was the head of a Christian charity, the Iwerne Trust, when he ran the holiday camps. The young Justin Welby was among the Christian young men who attended the camps. The camps were where public school evangelical Christians were sent if they were deemed to have potential as future leaders in the Church of England.

Writing in the Telegraph, the Christian commentator Anne Atkins describes the time she was "sent down" from one of the summer camps because she did not fit in.

She had been invited because her brother was an officer at the camp.

She says: "Within twenty four hours I felt a complete freak. Unknown to me, it was a world of extreme sexual apartheid. We were confined to the kitchen bashing spuds. The men, glorious in the sunshine and their cream cricket sweaters, played sports; gave talks in the meetings; swam and batted and even I believe flew aeroplanes.

"I was discreetly steered away from volunteering for a helicopter trip advertised over breakfast; told off for stopping to chat to a young man I was introduced to destined for the same Oxford college; then for agreeing to play tennis with my brother (he was not); and finally for talking to some boys who lay down near us at the swimming pool. It was the last straw: it was politely suggested I should leave, as I didn't fit in."