As 'Hacksaw Ridge' Is Released, A Baptist Minister Reflects On Lessons From His Conscientious Objector Father

The Baptist minister son of a Christian World War II conscientious objector has compared the dilemmas of wartime with those facing Christians during the presidency of Donald Trump.

And he said that while he would find it hard to pick up gun himself, he could not justify doing nothing in the face of evil such as Islamic State.

Rev Gethin Russell-Jones was speaking to Christian Today on the eve of the release of Mel Gibson's Hacksaw Ridge, which features the World War II story of Desmond Doss, an American pacificist combat medic and Christian.

Ross refused to carry or use a firearm or weapons of any kind. He became the first conscientious objector to be awarded the Medal of Honor, the United States of America's highest military award, for service above and beyond the call of duty. The film has received six Academy Award nominations and three Golden Globe nominations.

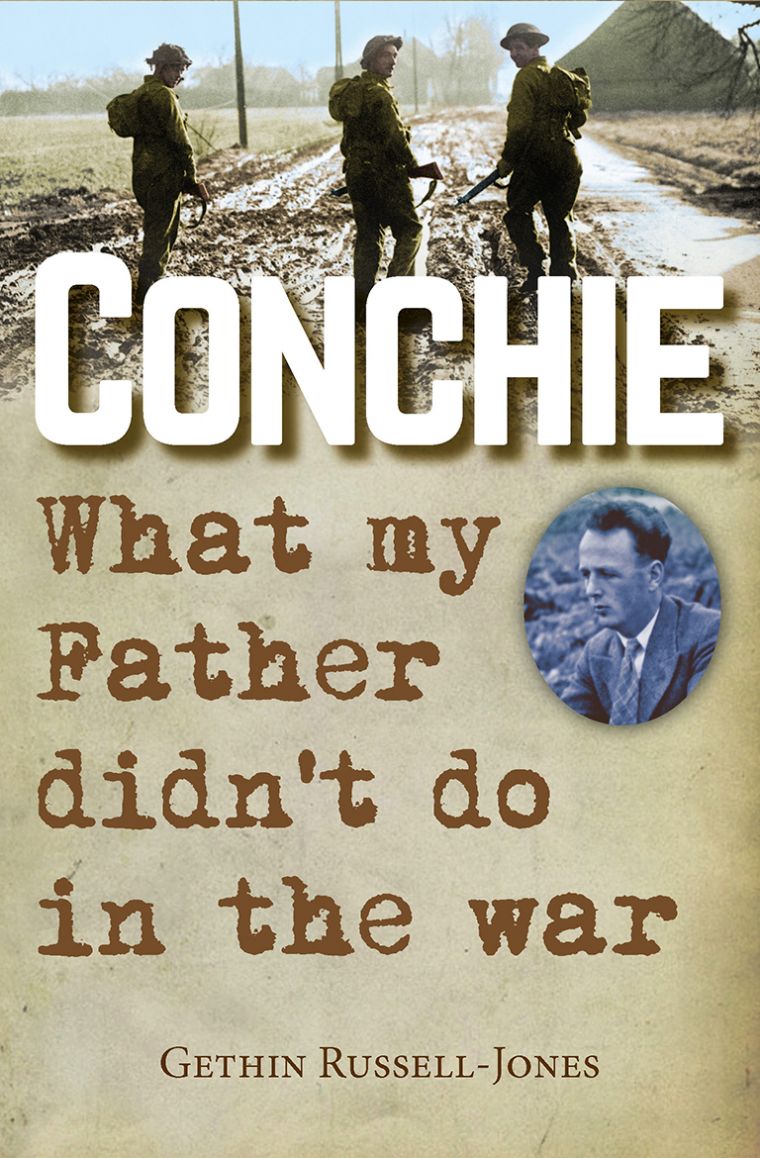

In his book Conchie, published last year by Lion Hudson, Russell-Jones described his quest to understand his father's decision to be a conscientious objector in World War II, a decision which led to shame and embarrassment for other members of his family

Russell-Jones, minister at Rhiwbina Baptist Church in north Cardiff, South Wales, said he grew up feeling deeply proud of his father, John Russell-Jones, also a Baptist minister.

"I knew at a young age that he called himself a conscientious objector but I did not really know what that was. He chose not to fight in the Second World War. I was a boy and felt proud because he was different from everyone else's dad. As a teenager, my feelings were more complex," he said.

He studied history at school and O-level Religious Education. For this, he had to read the German theologian and wartime dissident pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer who was hanged by the Nazis for his links with the plot to assassinate Hitler.

"Although Bonhoeffer would not fight, he realised he had to do his part. I suddenly thought, there is more to this than meets the eye.

"Bonhoeffer's line is that sometimes it is more evil not to do something than to do something. That began to churn me up."

He then found himself challenged by his own response to the Falklands war, when the possibility of a draft was discussed briefly. He disputed the morality of this war and realised he did not want to fight.

"But I am not sure that was because of principle. I just did not want to do it. I began to question my father's motives."

At the same time, his own faith was developing. Raised a Christian, his parents were clear that he needed his own experience of Christ.

"I began hoping for some kind of dramatic experience, which came in the end when I was 16. I am not to this day sure whether I was born again or simply became aware of God's love in a way I had not been before. From that point, though, I can say I knew God personally."

He had a second "renewal of faith" when living in London in his early 20s, and was walking on Streatham Common with a bad hangover. He experienced a "call" – heard a voice challenging him about the direction his life was taking. That same year, 1983, the Bible Society published a report about declining Christianity in England and Wales. "I had this sense in my heart – I knew I had to do something about this."

This took him to Bristol Baptist College and then ordination.

Today, he finds he is challenged by the pacifist approach.

"In terms of myself, I support Bonhoeffer's view, that there comes a point where doing nothing isn't enough. We have to do something. My father withdrew into himself. He was hijacked by this withdrawing. I would like to think that I would be a bit bolder."

The election of Trump is a case in point.

Russell-Jones said: "I am alarmed at the way so many American evangelical Christians are responsible for putting Donald Trump in the White House. I am praying there will be some kind of prophetic voice that emerges in the United States that can make itself heard above all this."

His father took the Bible – and the command not to kill – at its word.

"Jesus told us to turn the other cheek, not to repay evil with evil, to love your enemy. It is very hard. This is my father's point – that you can't read the Gospel and the Sermon on the Mount and then pick up a gun. He took it literally.

"The message of the Cross is one of sacrifice. Jesus offered Himself without resistance. This turns a lot of stuff on its head and raises questions around war, conflict and retaliation.

"So we are not allowed to put up walls against the people we do not like. But if Islamic State are coming your way, you cannot simply run away or let them do what they like. That would not be justice."

Extract from 'Conchie' by Gethin Russell-Jones

This is what conscience looks like. It's a fourteen-year-old boy sitting anxiously on a sofa late in the afternoon. He's fondling a bloodstained tissue as his parents look at the purple swelling around his right eye. A knock on the front door and in comes his grammar school form teacher and out comes the story. My brother Iwan had been playing football that lunchtime, during which he had been assaulted by the school bully, who for no explicable reason punched him several times in the face. To the consternation of everyone, Iwan had not retaliated and had walked away with a bloodied nose and mouth. None of his friends understood his reaction and neither apparently had his teacher. So this was his question to my brother: "Iwan, why didn't you fight back? You were entitled to defend yourself. This question has been bothering me since school ended and I had to ask you." Iwan, who has never been a timid soul, had a clear and surprising answer. "It was the way I was brought up, sir, never to take revenge on anyone. It would have gone against my conscience."

This book is about the power of conscience and the way it influenced my family's story. In particular it's about my father's life before, during, and after World War Two. I'm going to tell the stories of the people, events, and ideas that shaped a decision he took as a 21-year-old man; a decision that still reaches into his family years after his death.

Most of us over the age of fifty have a war story. In one way or another, our fathers and some of our mothers were involved in the Second World War, willingly or not. And whether alive or dead our grandfathers also gave report of life and death in the First World War, the Great War. Beneath the largely peaceable skies of the northern hemisphere, we are only one generation removed from events that rocked the world and shaped the culture we inhabit.

Take my friend Dave for example. As we sit sipping coffee and he munches on a teacake, he asks me about this book. I explain it's about pacifism during World War Two. He then discloses two extraordinary war tales. His father, Ron Clague, was one of the first to liberate Dachau, whose infamy as a Nazi death camp has gone down in history. Such was the disfiguring and deadly evil witnessed by this twenty-year-old, that he barely spoke about it. Dave talked also about Ron's best friend, Ernie. As a teenager, Dave casually asked Ernie what he had done in the war and he received a reply that had never been given until that moment. Holding back tears and trying to contain big, painful emotions, Ernie talked about the Death Railway, made famous in the films The Bridge on the River Kwai and The Railway Man. Captured as a prisoner of war by the Japanese, he was forced to work on the vast railway that stretched from Ban Pong in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar (Burma). It was a brutal and torturous regime and many POWs were beaten to death. There were also a huge number of deaths among the Romusha, Asian civilians forced to work on the railroad. Over 12,000 British, Allied, and American servicemen alone lost their lives. It is said that for every piece of track laid, someone died.

A few days later and I am having coffee with Martin, another friend. In the course of our conversation, I casually mention the subject of this book and he drops a bombshell. His grandfather Maurice Allen was a conscientious objector (CO) in the First World War, whilst his father Dennis was a CO in the Second.

I too have a story; I'm just not sure whether I like it that much.

Conchie, What My Father Didn't Do In The War, By Gethin Russell-Jones. Lion Hudson. ISBN 978 0 7459 6854 4