Who is my neighbour? Lessons from the edges in community

He wears a black woollen cap pulled down over his hair. I once saw him take it off and glimpsed the plaits beneath; but perhaps he feels his hair is too matted or knotted by the rain. He doesn't speak much. It is his actions that speak.

And slowly, over the weeks, he has lifted up his eyes and his face has lit up into a smile and his kindness has filled the place. He came as a guest to our International Group – a place where we offer hospitality to those without recourse to public funds and end up discovering the hospitality they offer to us, so that we are no longer sure who is the guest and who is the host. It began with the washing up – simply, quietly taking control of dirty dishes, washing and rinsing at speed, laughing when I tried to help. The sink becoming the place of hospitality and meeting – washing away the mess and grease, plunging into clean water. Then he began on the pots, the serving trays, the surfaces, the serving counters – cleaning so everything gleamed, clearing away, putting back – his smile and laugh radiating outwards. He galvanized us.

Sunday after Sunday, the quietest became the one we all depended on most, the one whose presence inspired us all. As we carry huge bags of rice back from Chinatown, he hurries on ahead of me with his two bags, and before I am halfway back he has returned empty-handed to help me carry mine. Walking 74 miles to Canterbury on our annual pilgrimage, when we, the slowest group of pilgrims, have staggered into the church halls in the evenings, he has reached there three hours before, sorted our luggage, and found our sleeping bags and a place to sleep. Nothing servile – but brave, self-sufficient, strong.

This man has crossed Africa, spent time working to raise money for his passage in Libya, crossed the Mediterranean in a boat that almost sank, crossed Europe, spent months in the Calais Jungle, getting to the UK God knows how. He has a kindness and an awareness of the needs of others that staggers. And yet he is so self-contained, demanding nothing – just this instinctive giving of self. He is 'fit': fit of mind, fit of body, fit of attitude; he fits the group. Without complaint, without request, without moan, without profit, without motive: he generously gives and we are made richer by his presence. He is the beloved disciple.

A tourist once entered our church and asked me loudly: 'Who are all these mummies in your church?' I didn't know what he meant at first. Then he pointed to all the hooded or blanketed sleeping people who sit in the box pews around the edges of our church. 'This lot – these mummies.' I was outraged. 'These people are my community,' I wanted to say.

During the renewal and renovation of the church, one of them said to me: 'I hope this is not going to be like a pub make-over. I mean, this is our church. We spend more time in it than you do.' They do. They are a constant reminder that this is why we are here. That the church is not just some club for its private members, or even worse, a tourist shrine – it is the home of all. These people are the church, just as we are. A church grounded in the reality of people's lives.

What I wanted to do was shout at that tourist. I wanted to tell him the names of those around the edges and their gifts and their qualities and to suggest that many of them were perhaps closer to God than he was. The only reply that came into my head was, 'They are our neighbours.'

But could I claim this? Were they our neighbours? How many of us in the worshipping congregation knew their names? We were the church of the homeless and yet many of the homeless we knew very little about. And perhaps like many churches we often did not do anything because we were not quite sure what to do. We thought, like people often think, that we ought to do something for them yet we might not be able to solve their problems so we did nothing.

Many of those sleeping in our pews were those with no recourse to public funds and it would be true that if we tried to help them there would be no easy solutions to their difficulties. But was that an excuse to ignore their existence? Does the fact that someone has difficulties and you can't solve them prevent us from making relationships? I asked for volunteers among the congregation to discover whether anyone was willing to help provide hospitality for these people. Forty people responded and in 2013 we founded the International Group, providing welcome for refugees and migrants who are facing destitution. It would not be an exaggeration to say that through this ministry we have discovered our neighbour, and our neighbour is no longer a person simply on the edge, but us, as we eat together, share together and offer one another the gifts of our hospitality. Who is the guest and who is the host? It is now difficult to tell.

We come from over 35 different countries. We speak many languages. We have experienced many different cultures. We come from different faiths, and also faithlessness. We each come with our own wounds, carrying the scars of our lives in our bodies and scorched in our memories. We carry our own hopes, our own achievements and insurmountable needs. We are different colours, ages, sexes, genders, sexualities.

We don't know all the answers. We know our failings. Some of us have money to generously share, some of us don't, but all of us have something to give. The greatest poverty is to believe that you cannot help another, and it is a real truth that it is those who believe they have least who in fact often seem to have the grace to give the most.

We all have the opportunity to be the Good Samaritan. That's the story. We come from many different places to this place where our journeys meet. Who are we? The truth is that we are all the body of Christ.

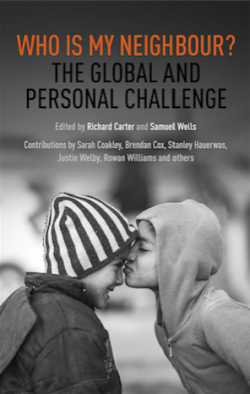

This article is an extract from 'Who is my Neighbour? The Global and Personal Challenge', edited by Richard Carter and Samuel Wells. Other contributors include Justin Welby, Brendan Cox, Rowan Williams and Stanley Hauerwas.

'Who is my Neighbour?' is published by SPCK, price £9.99.

Richard Carter is associate vicar for mission at St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square, with special responsibility for outreach to refugees.