What's wrong with Jordan Peterson? 12 Rules for Life, and why they aren't

My introduction to Canadian philosopher-psychologist Jordan Peterson came via a Channel 4 interview by Cathy Newman, one of its star presenters, a year ago. It was lots of fun. Newman's approach was hostile, extremely so. She zeroed in on what she assumed were his views on men and women, attempting serial paraphrases of what she thought he meant: 'So what you're saying is...' 'No, that's not what I'm saying at all,' was his serial reply, with Newman at one point reduced to an awkward silence. The general consensus was that she had been comprehensively trounced, though Channel 4 sportingly put the whole interview on YouTube so viewers could make their own minds up.

I admit it: I enjoyed it, and when it was over I watched it again, like Father Ted with Bishop Brennan's dodgy holiday video.

But Peterson, I discovered, was as polarising as Marmite. Precise, intense and rather menacing, he came to prominence in 2016 when he released a series of videos critiquing the Canadian government's Bill C-16, which added gender identity as a prohibited ground of discrimination. Since then he's become a YouTube star with 1,795,000 subscribers to his channel. He's in demand as a conference speaker, interviewee and debater.

Generally speaking, he is loathed by liberals and loved by conservatives – including and especially Christian conservatives. Partly this is because, as a disciple of Jung, he takes religion seriously, with intense and thoughtful readings of Old Testament Scripture passages. Partly it's because of what propelled him to prominence, always a hot-button issue with this demographic – Peterson argued it was wrong to compel him to use the 'preferred gender pronouns' of transexual people and that it was 'Marxist' to try to make him (he is a serious student of authoritarian regimes and their philosophies).

His popularity with conservatives is also because of his views on gender relations – he believes there is a 'crisis of masculinity' and questions concepts such as 'patriarchy'. He's also a trenchant critic of postmodernism and 'identity politics'; academic disciplines like women's studies and sociology have been corrupted by Neo-Marxist ideology, he thinks.

Hostile reaction tends to be at a visceral level, with Peterson accused of being a transphobic, chauvinist Nazi apologist in terms unsuitable for a family website. He is indeed beloved by the alt-right, who are attracted by his rebel persona, though he has no particular sympathy for them. There's another reason for his identification with the right, which we'll come to.

Though he has written dozens of academic papers in his field of clinical psychology, he's only written two books. Maps of Meaning in 1999 explored how people construct their beliefs. 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos (2018) is a more popular book originating in his contributions to the Quora website.

The advantage of 12 Rules is that it provides readers with Peterson in one place. So what does it say? Is he really the right-wing Christian misogynist his enemies – and indeed, some of his friends – like to claim? And if he's ideologically dangerous, where exactly does that danger lie?

12 Rules reads, on the face of it, like any self-help guide. 'Stand up straight with your shoulders back', 'Compare yourself to who you were yesterday, not to who someone else is today', 'Set your house in perfect order before you criticize the world' – they all sound pretty uncontroversial.

Where Peterson scores, however, is in adding layers of philosophy, science and expertise in psychology to those bits of folksy wisdom. As a result, reading him – and even more, listening to him – can make you feel that you're actually learning something – though that feeling starts to wear off when you start to think about what he actually says.

And this is where lobsters come in. Lobsters are like us, he says. They are motivated by the same desires for safety, territory and sexual success. They fight, and a beaten lobster is truly beaten: 'A vanquished competitor loses confidence, sometimes for days.' Even worse: 'If a dominant lobster is badly defeated, its brain basically dissolves. Then it grows a new, subordinate's brain – one more appropriate to is new, lowly position.'

So, 'Stand up straight with your shoulders back': heirarchies matter, and if you're at the bottom of the pile you will be sad, unhealthy, have less sex and die sooner.

12 Rules is quite a rich and thoughtful book, but this is the thread that runs through it: that we are shaped, spiritually, emotionally and psychologically, by forces beyond us, and as far as possible – which may not be very far – we need to take control of them. In the chapter 'Treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping' it's the ancient clash between order and chaos – which he badges, in terms that have infuriated feminists, as masculine and feminine. In 'Make friends with people who want the best for you' it's the damaging effects of people whose lives are chaotic, who drag us down when we try to lift them up. In 'Compare yourself to who you were yesterday, not to who someone else is today' it's the destructive inevitability of competition – to be dealt with by choosing a different ladder to climb ('there is not just one game at which to succeed or fail') – and so on.

Peterson's adherence to evolutionary psychology as an explanatory mechanism for human behaviour informs his controversial views on gender, too. Boys and girls are different. 'Boys are suffering in the modern world,' he says. 'Boys' interests tilt towards things; girls interests tilt towards people.'

It's because of assertions like this that Peterson has been pilloried by liberals (Cathy Newman, for instance). While he is adamant that he believes in equality of opportunity for men and women, he believes equally firmly that equality of outcome – where men and women are equally represented in engineering and nursing, scaffolding and primary teaching – isn't a desirable goal.

'Strikingly, these differences, strongly influenced by biological factors, are most pronounced in the Scandinavian societies where gender-equality has been pushed hardest: this is the opposite of what would be expected by those who insist, ever more loudly, that gender is a social construct. It isn't. This isn't a debate. The data are in.' In other words, left to themselves, men and women will naturally drift in different directions. (There's more on this here.)

For his critics, this is all very irritating. His Scandinavia example notwithstanding, they argue that social conditioning has a far larger part to play in establishing gender roles than he admits. Furthermore, for many in the increasingly moralised world of identity politics, merely arguing that men and woman are different and that behavioural outcomes are different puts him in the wrong because all it does is reinforce stereotypes.

But to be fair, Peterson has given them plenty of ammunition, and not just in 12 Rules. He rejects the idea that women are globally disadvantaged by 'patriarchy', for instance, on the grounds that men do more dangerous jobs and fight more in wars. He's a climate change sceptic, saying we don't know enough about it and don't know what do to about it anyway. And while that order/chaos dichotomy is ancient, it's hard to think of a particular reason for it to be male/female other than its shock value.

He takes a dark delight in playing with interviewers, especially those he thinks don't get him. Interviewed by Vice, he says sexual harassment in the workplace won't stop because 'we don't know what the rules are'. 'Here's a rule,' he says. 'What about "no make-up in the workplace"?' Cue bewilderment from the journalist. But: 'Why should you wear makeup in the workplace? Isn't that sexually provocative?' And after Vice's incoherent splutter: 'Why do you make your lips red? Because they turn red during sexual arousal, that's why. Why do you put rouge on your cheeks? Same reason. How about high heels? What are they for? They're there to exaggerate sexual attractiveness.'

None of this is original, of course. But a less hapless interviewer raises the same question at Madrid's Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, and frames the issue correctly. Peterson, she says, is 'defending nature, and the impact of biology on human conduct, on human interests, on human choices, against that big movement which we call social constructionism' – the idea that societies, rather than biology, create values, meanings and identities.

And here we get to the root of the Peterson problem – and yes, there is a problem. His defence of 'nature' is part of his appeal to conservatives. All that about transgender and gender roles is catnip; here's a real psychologist who backs up the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. And if he isn't exactly a Christian, he takes the Bible seriously, in his own way, and he who isn't against us is for us.

If Peterson appeals – as he does – disproportionately to aimless young men who are attracted to his bracing advice about cleaning their rooms, taking responsibility and making something of their lives, we might wonder why. And here's where things get complicated. Because he's right: gaming, smoking weed and staying in bed all morning instead of studying and exercising aren't good for you, either in body, mind or spirit. A Peterson disciple has got that much going for him, and is probably higher up the heirarchy because of it.

But – and this is what makes his popularity among Christians so baffling – the rationale for all this, in Christian terms, is profoundly flawed. For Peterson, the millions of years of human evolution that lie behind us shape our behaviour today at a fundamental level. Integral to that is the urge to dominate, to control and to succeed at the expense of others.

Now, it is ridiculous to accuse him – as some have done – of sympathy for totalitarianism and fascism; he's profoundly aware of their dangers. Neither does he follow the logic of his position to its bitter end: he is personally strongly motivated by altruism (the sections of 12 Rules where he describes the neglected child of another psychologist, and where he writes of his daughter's rheumatoid arthritis, are truly moving). But he attracts a particular kind of follower because he validates their desire to dominate women, to be respected, to be powerful and to win.

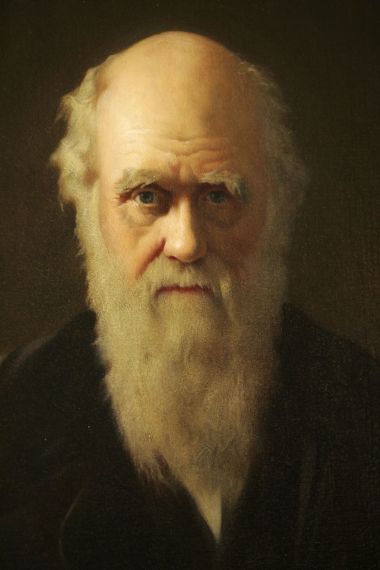

Peterson has staked out a space in one corner of the triangle identified by Terry Eagleton, of Marx, Freud and Darwin. Marx taught the world we are influenced by vast economic forces. Freud taught us that we're motivated by the unconscious workings of our deep minds. Darwin taught us that we're the animal products of millions of years of learned behaviour.

And this is where Peterson is so profoundly anti-Christian, because he argues that we should go with the grain of our instincts. (It shouldn't need saying that he doesn't therefore say that 'might is right', though it probably does.) But Christianity contradicts his entire philosophy, because it challenges and promises liberation from all the forces that keep us captive. That's not to say they don't exist, of course; but they don't have to control us.

In fact, of course, Marx, Freud and Darwin all have their critics. Peterson's own angle, the Darwinian one, can be nuanced by a greater understanding of the role of society in mitigating the chimpanzee tendency (graphically and horrifyingly expounded in 12 Rules). One study claims to show that hunter-gatherer societies – the earliest in human development, and just yesterday in evolutionary terms - are egalitarian rather than patriarchal in form, arguing torpedoing one of Peterson's ideas.

But it would be foolish to argue that our evolutionary history has simply nothing to do with how we are made today. That is not, however, the point: for Christians liberation from 'sin', whatever its origins, is what we're about.

And when Jesus said, 'whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first among you must be your slave' (Matthew 20: 26-17), and 'since I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to wash each other's feet', he was upending the idea of heirarchy altogether. (To show how profoundly rooted in the earliest Christian community this idea was, consider Paul's fury at the Corinthians over their abuse of the Lord's Supper in 1 Corinthians 11).

Peterson's take on 'Do unto others'? 'If I am someone's friend, family member or lover, then I am morally obliged to bargain as hard on my own behalf as they are on theirs...it is much better for any relationship when both partners are strong.' As a clinical psychologist who's seen what happens when people are bullied and traumatised, yes: as a general guide to life? Christians would probably prefer, 'Be completely humble and gentle; be patient, bearing with one another in love' (Ephesians 4:2).

And this is where Jordan Peterson is in fundamental conflict with Christianity, which makes his appeal to some Christians the more surprising. But perhaps not: living as a Christian always involves a continuing struggle to separate the wheat of the gospel from the chaff of the culture, and we don't always do it very well. Today's church is bedevilled by various temptations. One is the cult of 'leadership', where churches look for the 'strong man' to tell them what to do; it's usually men, but women can be 'leaders' too, if they do it like men. When we fetishise leadership we buy into Peterson-style heirarchical thinking. Another is complementarianism, which baptises men's primitive instincts to dominate and oppress; though Peterson does believe in equality of opportunity.

Another bedevillment, particularly in evangelical circles, is a failure to think deeply and clearly about scripture and human nature. There is nothing particularly new or startling about Peterson's treatment of Genesis if you've read good commentaries, but his reflections on these Old Testament stories enthral far more people than ever hear a decent sermon on them. Is it time for evangelical preachers to up their game?

Jordan Peterson will, no doubt, continue to divide not just the chatterati, but the church. We should not dismiss him out of hand, but neither should we celebrate him. He's not on our side.

Mark Woods is the author of Does the Bible really say that? Challenging our assumptions in the light of Scripture (Lion, £8.99). Follow him on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods