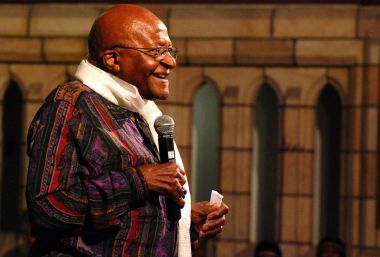

Tutu's enduring anti-apartheid legacy

Like Dr Martin Luther King Jr and Nelson Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu will go down in history as an icon of the twentieth century. He was a Christian leader who, against enormous odds and opposition, rescued his nation from the bloodbath and the revenge many predicted that blacks would exact upon white South Africans after decades of humiliation, oppression and murder under apartheid.

But this great African Christian leader played a leading role in both pre- and post-apartheid South Africa. Recognizing the critical part he played during the time when the African National Congress (ANC) was banned by the South African government, and when most of its leaders were in exile, President Nelson Mandela stated: "Here was a man who had inspired an entire nation with his words and his courage, who had revived the people's hopes during the darkest of times."

And in his eulogy, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa acknowledged the "different but complementary" roles played by these two colossi in South African political iconography: "While our beloved Madiba (Mandela) was the father of our democracy, Archbishop Tutu was the spiritual father of our new nation."

Archbishop Tutu (or 'Arch' as he was popularly known) knew both suffering and joy. As a young boy he contracted polio, leaving him with a weak right hand and forcing him to write with his left hand. At age 14 he contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalized for nearly two years.

During this time, he was visited regularly by the radical Anglican priest, Trevor Huddleston. As a friend, mentor, and inspiration, Tutu credits Huddleston with his becoming an ordained priest in 1961 at the age of 30.

Tutu tells us that it was this white priest who gave him his first pocket New Testament; and if his memory served him well, he relates an early experience of either Huddleston or Father Raymond Raynes doffing their hat to his mother as a mark of respect. Clearly this was not the norm in South Africa when he was growing up.

In his inimitable way, Tutu would later admit that he had no intention of becoming a priest – neither from "noble motives", nor from "an overwhelming sense of vocation".

Indeed, like his father before him, he ended up training to be a teacher. But this was not his first love: he wanted to be a doctor but could not afford the fees. Desmond obtained his teaching diploma in 1953 and a year later received his BA by correspondence. He married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane (also a teacher) in 1955. They both resigned from their teaching with the enforcement of the government's Bantu Education Act, which was undoubtedly a turning point in the couple's life.

This Act was passed in 1953 by the Nationalist dominated parliament. Its intention was, as Nelson Mandela would argue in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, "intellectual baasskap, a way of institutionalizing inferiority". Neither Desmond nor Leah wanted to be seen as "collaborating with this travesty", as they saw it. For Tutu, the race-obsessed ideologues of apartheid – especially Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, minister of Bantu Education, and later Prime Minister of South Africa (1958-1966) – wanted an education designed to prepare black children for "perpetual serfdom, as the servants of their high and mighty white bosses and mistresses".

Verwoerd, referred to as "the architect" and "high priest" of apartheid by Tutu in his book No Future Without Forgiveness, engaged in a specious piece of racist logic that went something like this: education must train and teach people in accordance with their opportunities in life. Since black (Bantu) children don't, and won't, have any opportunities under apartheid there is, therefore, no reason to educate them. According to Verwoerd, there was "no place for the Bantu in the European community above the level of certain forms of labour".

This racist education philosophy aroused widespread hostility from both blacks and whites, with the exception of the government's major supporters – the Dutch Reformed Church and the Lutheran mission. Tutu was deeply affected by it. Schools which did not go along with government policy would receive no funding and the policy caused divisions; many schools decided to close rather than go along with the government's education policy.

In the Anglican ranks, there were divisions. For example, Bishop Ambrose Reeves of Johannesburg took the radical step of closing his schools with 10,000 students enrolled, while the Archbishop of the Church in South Africa decided to hand over the rest of the schools to the government, anxious to keep children off the streets.

The politics of education was a lightning rod for student protests and demonstrations, sparking the Soweto uprising of 1976 where security police killed hundreds of student demonstrators.

To Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress, the Act was a "deeply sinister measure designed to retard the progress of African culture". If enacted it would, according to Mandela, permanently set back the freedom struggle of the African people, blighting the "mental outlook of all future generations of Africans".

For Tutu, the segregated and inferior education advocated by Verwoerd at the time was consistent with the "total irrationality of racism and apartheid". This irrationality was clearly demonstrated in Verwoerd's response to the provision of food to schools. One of the consequences of the Bantu Education Act was the end of the feeding schemes that were introduced into some black schools. When asked why this cheap way of ending malnutrition in schools had stopped, Verwoerd replied: "If we can't feed all those black children, then we shouldn't feed some. If you could not feed all you shouldn't feed any." According to Tutu, this would be akin to saying, "We won't treat this TB patient because we can't cure them all."

Desmond Tutu was undoubtedly a thorn in the side of the racist South African government (its 'Public Enemy No 1'). But he was also a fierce critic of President Jacob Zuma and the corruption he saw in the post-apartheid ANC government. Like Prince Albert John Luthuli before him, and Nelson Mandela after, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1984 for his role in opposing apartheid.

He, of course, was popular before then as, among other things, the first black Dean of St Mary's Cathedral in Johannesburg (1975), Bishop of Lesotho (1976), and General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches (1978), a role he used to spearhead his fight against the apartheid regime.

Unsurprisingly, President Mandela appointed him to chair South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1995. Tutu said this was the "hardest job" of his life. This controversial commission (regarded by whites as a witch hunt and by blacks as allowing racist murderers to 'get away with murder') aimed at dealing with the country's brutal past, offering amnesty in return for confession. Today, many of the recommendations in Tutu's five-volume TRC report have been ignored by the government, including reparations to the victims and families who testified. Archbishop Tutu later called for a wealth tax on all white South Africans. This was also ignored by the government.

Carried in a simple wooden coffin and his ashes interred in St George's Cathedral in Cape Town, the man who was South Africa's moral compass is now at rest in the presence of the God he faithfully served during South Africa's darkest and most turbulent decades. His example and legacy will continue to inspire a new generation in the perpetual struggle for justice, inclusion, and peace.

He was a pastor, preacher, theologian and a fearless prophet to his nation and the global community. Theologians especially should take note of what 'Arch' said about 'God's dream' in his beautiful little book God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time:

'"I have a dream," says God. "Please help Me realize it. It is a dream of a world whose ugliness and squalor and poverty, its war and hostility, its greed and harsh competitiveness, its alienation and disharmony are changed into their glorious counterparts, when there will be more laughter, joy, and peace, where there will be justice and goodness and compassion and love and caring and sharing. I have a dream that swords will be beaten into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks, that My children will know that they are members of one family, the human family, God's family, My family. In God's family, there are no outsiders. All are insiders.'

Every now and then, great souls come among us to remind us of who we are as image bearers of the divine, and what we can become during our short sojourn here on this fragile planet. Desmond Tutu was such a soul. I only met him once, but that was enough to confirm all that I had read and knew about this courageous priest and prophet of justice and peace in South Africa.

Whether you are black or white, Protestant or Catholic, Muslim, Buddhist, or Jew, this diminutive man was a giant of our times, a global icon of righteousness and humanity for believers and non-believers alike.

May he rest in peace, and light perpetual shine upon him.

Dr R David Muir is Head of Whitelands College, University of Roehampton, and Senior Lecturer in Public Theology & Community Engagement. He is the Director of the Centre for Pentecostalism & Community Engagement at Roehampton University and executive member of the Transatlantic Roundtable on Religion and Race (TRRR). In 2015, he co-authored the first Black Church political manifesto, produced by the National Church Leaders Forum (NCLF). He is a Trustee of the National Churches Trust.