Thomas Becket and the costly sacrifice of Christian witness

It is the stuff of modern politics and great drama: two men, working together with a common purpose, ruthless in pursuing their aims, their friendship entwined with their working together in high office. And then it all goes spectacularly wrong.

Perhaps that is why the story of Thomas Becket and Henry II resonates so much with contemporary audiences and why playwrights T.S. Eliot and Jean Anouilh found so much dramatic material in the tale of the archbishop and the king who fell out, leading to the death of Becket. Becket's story, as recounted above, could be set today, even though it took place in 1170.

But as we mark the 850th anniversary of Becket's slaying, his story is so much more than a tragic row caused by friendship going wrong. It is a reminder of how integral to Christian faith being a witness to truth is – and how that witnessing can lead to paying the ultimate sacrifice of one's life.

Becket and Henry II worked together from 1155 when Henry appointed him as chancellor. For seven years they were close allies, their bond sealed by Becket's success at raising revenues for the king from landowners and bishops, with the chancellor often showing utter ruthlessness. No wonder that Henry thought he could trust Becket to be similarly compliant when he made him Archbishop of Canterbury, then a higher office than chancellor, and so he had him ordained.

But being archbishop changed Becket. His eyes were now focused on responsibilities greater than his allegiance to the king: loyalty to the Church and to God. Cooperation was replaced by conflict. And Becket would not be swayed otherwise.

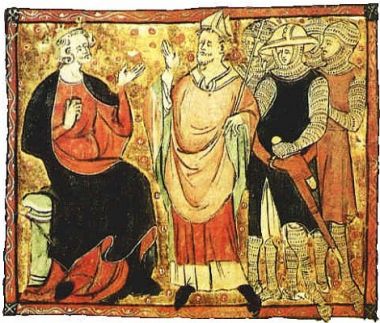

Matters came to a head in 1170, eight years into his episcopacy. Henry, frustrated by Becket's intransigence, is believed to have said in fury: "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?" Whatever the phrasing, it led four knights to head to Canterbury, determined to show their fealty to the monarch through their confrontation with Becket. On December 29 they arrived in the city, and made for where Becket was having dinner. After a furious row, they followed as Becket made for the cathedral. There, armed with knives and axes, they cut him down, leaving his brains smeared across the cathedral floor.

The murder shocked Christian Europe, and Canterbury quickly became a place of pilgrimage, with Becket recognized as a martyr and canonized in 1173. Fifty years after his death, Becket's body was moved to a shrine, his new tomb bedecked with jewels and attracting huge numbers of devotees. Quite how diverse they were was illustrated by Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, written around 1400. But within less than 150 years, the shrine was destroyed on the orders of Henry VIII.

In more recent times, though, interest in Canterbury as a place of pilgrimage has grown, with people visiting, not to see an extravagant tomb, but to recall Becket's death and what it stands for in the very place where he was killed: killed because he would not compromise, because he was prepared to stand up for what he believed in. His integrity remains appealing to people, regardless of their own convictions. To Christians, though, Becket is a reminder that faith matters more than allegiance to earthly powers and that being a Christian believer is about being a witness – a witness that on occasion pays the ultimate sacrifice of their life.

It is witness that is above all the essence of martyrdom and the word martyr derives from the ancient Greek for witness. And with Christ's own sacrifice of his life being at the heart of Christianity, those who follow in his footsteps giving up their own lives have a special place in Christian history, from the first martyr, St Stephen, celebrated on December 26, to the apostles Peter and Paul, and onward through the ages.

While the earliest martyrs were put to death by pagans, one of the most terrible aspects of Christian history is that plenty of Christ's followers met their deaths at the hands of fellow believers. Becket was slain by other Christians, as was Thomas More, executed by the destroyer of Becket's tomb, Henry VIII. Like Becket, More could not countenance obeying a king if it meant he betrayed his own religious beliefs. Nor did Catholics have a monopoly on integrity during the dark days of the English Reformation: Protestants, too, were executed for staying fast to their deeply held faith. Today, in our more ecumenically minded world, Christians of different denominations can recognize the witness of past martyrs from other Churches.

But martyrdom is not something of the past. It remains the price that Christians pay for their witness, from those who speak up for justice to those who will not renounce the faith that means so much to them. They follow the same path as Thomas Becket, 850 years on.

Catherine Pepinster is the author of Martyrdom – why martyrs still matter, out now from SPCK.