The price of Christian pacifism: How prison graffiti tells a story of faith

Graffiti left by First World War prisoners in Yorkshire's Richmond Castle is to be preserved by English Heritage at a cost of £365,400.

It was created by a group of extraordinarily brave men, who in their lifetimes were despised by almost everyone. They were conscientious objectors who refused to fight in what most people thought was a war for national survival. They paid a very high price for their stance, which for most of them was driven by Christian faith.

The "Richmond 16" included a Sunderland FC footballer, a clerk at the Rowntree's chocolate factory in York, and a bookseller from Ely. Among the group were Quakers, Methodists and Jehovah's Witnesses. There were also socialists who wouldn't take up arms in a capitalist war.

Right from when conscription was first introduced in March 1916, it was recognised that some men would refuse to fight. There was a "conscience clause" to allow people with genuine religious convictions to opt out. So Quakers, who believed in non-violence, ought to have been exempt. Other Christian pacifists hard a harder time, since their denominations didn't teach pacifism – and much depended on the attitude of local committees. Many were likely to see applicants for exemption as cowards or shirkers. Some pacifists served in non-fighting roles – some of them very bravely in the ambulance services, for instance – but others were absolutists, who would have nothing to do with the war. If they could not convince the panels of their sincerity they faced imprisonment, or worse.

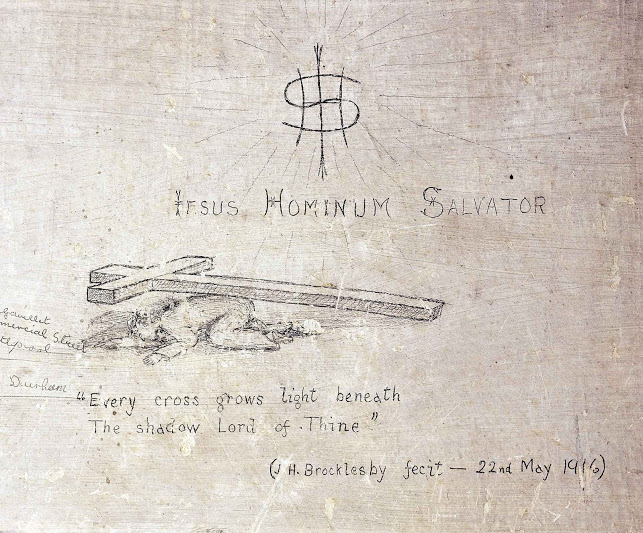

Among these absolutists were the Richmond 16. One of them was Bert Brocklesby, a Methodist, who paid a high price for his convictions. When war broke out, he said: "However many might volunteer yet I would not. God had not put me on earth to go destroying his own children."

A large, ebullient man who was a local preacher, he made his feelings about the war known in a sermon. The condemnation was instant, with many accusing him of cowardice.

Bert was one of the first to face a tribunal. The clerk asked: "Supposing you were in a corner with your back to the wall and six men were before you with open sword or fixed bayonet, would you not do something if you had a revolver in your hand?" Bert replied: "The Sixth Commandment says 'Thou shalt not kill'. I take it it is better to be killed than kill anyone else."

He was sent off the army's newly formed Non Combatant Corps – or the No Courage Corps as it was soon nicknamed. But Bert was an absolutist and refused to go. His father supported him: when he was told he should turn his son out of the house, he said: "I would rather Bert be shot for his beliefs than abandon them."

His own family stood by him, but in the end his fiancée could not reconcile his beliefs with the death of her brother at the hands of the Germans and the engagement ended.

Brocklesby's story was typical in how it highlighted family stresses and the cost of discipleship. The authorities were determined to make an example of the Richmond 16. They were sent to France and told that if they refused to obey orders they would be shot. Only an intervention in Parliament saved them. They were tried by court-martial and sentenced to death, but after a deliberately sadistic pause they were told the sentence was commuted to 10 years imprisonment. They spent the war breaking rocks in a quarry near Aberdeen, branded as "degenerates" by the local press.

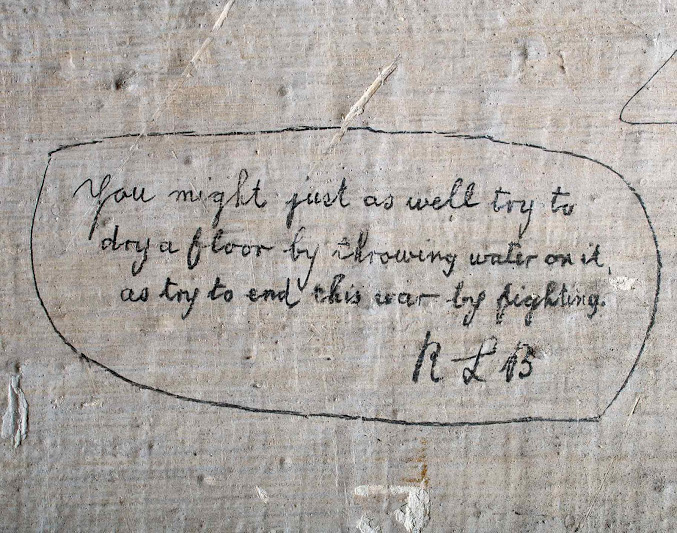

The graffiti they created in Richmond Castle is poignant. There are Scripture texts, hymns, scraps of poems and pictures. But the cell block was not well built; it is damp, the plaster is crumbling and the graffiti is in danger of being lost. Now the roof and walls of the cell block will be repaired and conservation specialists will treat the graffiti most at risk.

Kate Mavor, English Heritage's chief executive, said: "It is remarkable that these delicate drawings and writings have survived for 100 years. Now we can ensure that they survive for the next century and that the stories they tell are not lost."

The First World War has faded out of living memory and conscription is no longer a realistic prospect in modern warfare, at least in the UK. But news of the grant comes just before International Conscientious Objectors Day on May 15. The day commemorates those around the world who refused to fight in war and celebrates those who continue to do so, either by refusing conscription or by actively resisting militarism. First World War conscientious objectors went on to form the Peace Pledge Union (PPU), one of the oldest pacifist organisations in the world. It cites as examples of conscientious objectors in modern Britain engineers who have reduced their prospects by refusing to work in the arms industry and people who withhold taxes in protest against military spending.

PPU coordinator Symon Hill said: "100 years ago, conscientious objectors were imprisoned in horrifying conditions for taking a stand against war. Today, in countries around the world, hundreds of people remain in prison for refusing to fight.

"In Britain, our bodies are no longer conscripted. But our taxes are conscripted to pay for the fifth highest military budget in the world. Our minds are conscripted as we are taught from an early age that violence is the solution to conflict and that unquestioning obedience is something to be admired. Even our language is conscripted, with preparations for war described inaccurately as 'defence' and 'security'. "As everyday militarism becomes more and more visible, we need to resist it with everyday objection."

Pacifism, particularly the absolutist form embraced by Bert Brocklesby and his fellow objectors, remains a minority position among Christians. But it isn't necessary to agree with someone in order to admire them. Bert Brocklesby, Sunderland player Norman Gaudie, Leonard Renton and the rest were martyrs to pacifism, and remarkably brave men. We can see this much more clearly than their contemporaries could, and we can be glad of their courageous witness even if we don't share their principles.