Terry Waite: After 5 years in solitary confinement, what did he learn?

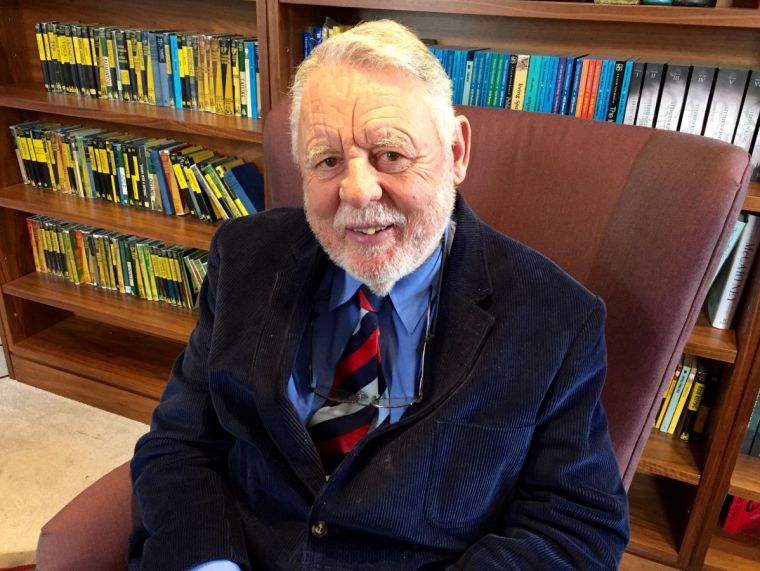

Terry Waite is a giant of a man.

His physical presence, his intellect, his sense of self-awareness and how he reflects on his experiences – there is an aura that commands respect.

It takes something special for more than 500 people to remain utterly silent in a stuffy, overcrowded marquee in a muddy field in Somerset. But at New Wine, an evangelical Christian festival, silent they stayed for more than an hour as Waite, a former envoy to the Archbishop of Canterbury, spoke of lessons learnt in his five years of imprisonment, solitary confinement and torture in Beirut.

Speaking to Christian Today afterwards the refrain he comes back to is the creativity that comes out of suffering.

Left for 1,763 days, most of which were without human contact, in his cell for 23 hours, 50 minutes a day, Waite wrote his book Taken on Trust in his head during that time.

He also composed poems and reflections, published in Out of the Silence, to keep himself sane.

In what seems like a gross underplaying of his experience he says: 'Everybody has suffered to a greater or lesser extent. The pain will always be there to an extent.'

He goes on: 'But it need not be debilitating. You can turn suffering into something creative.

'Many of the great creative acts – works of art and what have you – have emerged from situations of suffering.

'Of course that is the central theme of the Christian faith. The cross – the symbol of suffering – beyond which lies the resurrection, implying suffering need not be the end.

'Suffering can be destructive and it can destroy but it need not and that's the point.'

More than 25 years after his release, he still speaks about it regularly and last year republished Taken on Trust which documents those years from January 1981 to November 1991.

Asked whether it was painful to relive that time over and over again in lectures and interviews he says: 'I talk about it because it's been utilised, I hope, in a creative way.'

He adds: 'You speak about the experience and you link it with the experience of other people who have had really difficult times and you demonstrate that something creative with it.'

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about Waite beyond surviving the torture, ill-treatment and illness, is how he survived mentally.

He speaks of having 'internal conversations' with himself and others inside his head. He refused to think too much of his wife and children for fear the agony would drive him insane. And he recited Anglican liturgy, hymns and some Psalms he had learnt through repetition as part of Church of England services.

After so many years of 'internal conversations' he admitted it was a struggle to adjust to 'external conversations' after his release. He found family meal times too much to cope with and woke up in the middle of the night to eat by himself for a time.

'If you have many years with an interior dialogue, you are speaking with yourself, you are creating imaginary characters, you are entering into that inner dialogue. There's no exterior dialogue. So it takes you a while to get accustomed to having external conversations,' he tells Christian Today.

'It just took a while to begin to learn how to communicate externally with others and both how to give and to receive.'

Aged 78 he is still deeply involved in reconciliation work and training hostage negotiators.

Asked whether he would re-enter the field and return to the Middle East he pauses to consider.

'I think I'm a bit old for that now because I think if I was captured again I don't think I would survive,' he says remarkably candidly.

He pauses again then goes on: 'If there was a situation where I could make a contribution that could not be made by other people then I hope I would say, "I will see what I can do."

'I certainly wouldn't back away from it.'