Remembering Selma: 50 years after the march that changed America

It's only 50 years ago that black people in the USA faced routine discrimination, exclusion and violence by the authorities which ought to have protected them.

No one would argue that every problem has been solved and that black and white people live together on terms of equality and mutual respect. Fifty years ago today, however, something happened that shone a light in to the dark heart of American racialism and became an emblem of change – and it's worth celebrating. 'Selma' is a film starring David Oyelowo and praised to the skies by critics: but Selma was a turning point in black Americans' fight for justice.

As well as poverty and violence, black Americans in the Southern states faced bitter hostility from segregationists who sought to restrict their right to vote. Civil rights groups such as the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) tried to organise voter registration drives.

In early 1965, they decided to make the town of Selma the focus of their efforts. The Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, was a fierce opponent of desegregation and the local county sheriff had led opposition to black voter registration (the result was that only two per cent of Selma's eligible black voters (300 out of 15,000) had managed to register).

Violence had marked resistance to the registration campaign from the outset. On February 26 white segregationists attacked peaceful demonstrators in the nearby town of Marion and a state trooper shot dead church deacon Jimmie Lee Jackson, leaving his family destitute.

It was this incident that inspired the SCLC to lead a protest march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery.

600 marchers led by John Lewis and Rev Hosea Williams set off on Sunday, March 7 – a day that was to become known as 'Bloody Sunday'. They got only as far as the Edmund Pettus Bridge when they were attacked by state troopers and others wielding billy clubs, whips and tear gas (County Sheriff Jim Clark had ordered every white male over 21 to report for deputization). A picture of one of the organisers, Amelia Boynton, lying wounded on the bridge was published around the world. President Lyndon Johnson was horrified and issued a statement deploring the state's conduct.

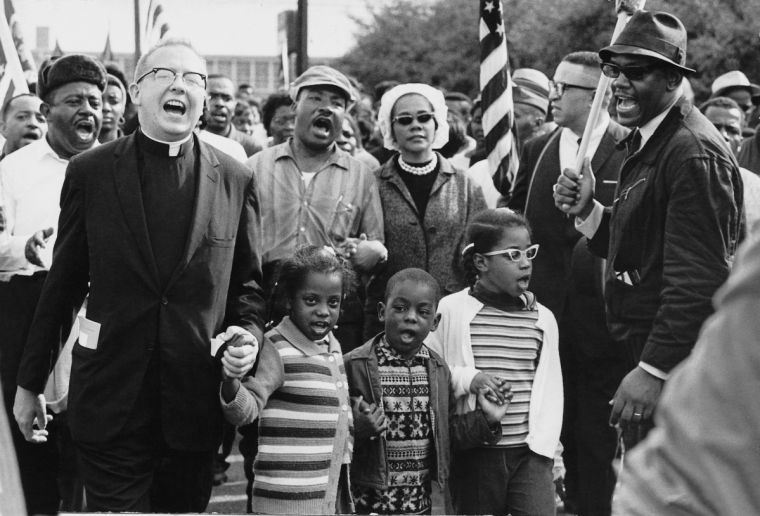

Two days later, the marchers tried again, this time led by Baptist minister Dr Martin Luther King, who the previous year had won the Nobel Peace Prize. It was chaotic: civil rights supporters had converged on the town from across America and were determined to march, but Judge Frank Johnson had issued a restraining order temporarily prohibiting it. King decided on a 'ceremonial' march to the bridge and back. Around 2,500 took part, but only the leaders knew they were going no further; there were scenes of confusion.

The day was to become known as 'Turnaround Tuesday' and it would end in tragedy. Three white Unitarian ministers who had come to take part in the march were attacked and clubbed by four members of the Ku Klux Klan and beaten with clubs. Rev James Reeb, from Boston, was taken to a hospital two hours away because it was feared the Selma hospital would turn him away; he died two days later.

Having been assured by President Johnson that the marchers would be protected whatever Governor Wallace said, Judge Johnson lifted the restraining order on March 17. The President put the Alabama National Guard under Federal control and sent 1,000 military policemen and 2,000 army troops to escort the marchers.

Four days later, on Sunday March 21, the march began with 8,000 participants, mostly black. Numbers were limited to 300 on two-lane stretches of the highway, but by the time they reached Montgomery numbers had swelled again and 25,000 people heard King's speech on the steps of the State Capitol building. He spoke of "creative nonviolence". He said that: "Selma, Alabama, became a shining moment in the conscience of man. If the worst in American life lurked in its dark street, the best of American instincts arose passionately from across the nation to overcome it." He said: "Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man."

King said: "I know you are asking today, 'How long will it take?' Somebody's asking, 'How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding, and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?' Somebody's asking, 'When will wounded justice, lying prostrate on the streets of Selma and Birmingham and communities all over the South, be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men?' ... How long will justice be crucified, and truth bear it?' ... 'How long?' Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

It was one of the great speeches of the 20th century. But in a sickening postscript, later that night the Ku Klux Klan assassinated Viola Liuzzo, a white mother of five who had come to support the marchers and was ferrying some of them back to Selma.

The Selma march was a watershed in the Civil Rights movement and led directly to the Voting Rights Act. President Johnson – who is himself both revered for his political bravery and reviled for his personal prejudices – told Congress: "Even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause, too, because it is not just Negroes but really it is all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome."

Racial equality in America has come a long way, but there is a long way to go. A 2010 study found that white families were five times richer than black, African-Americans make up 40 per cent of prison inmates but are only 13 per cent of the population, and they are far more likely to be killed by the police than whites. The education gap is vast, too: figures from 2014 showed that only seven per cent of black high school seniors are proficient in maths, compared with 33 per cent of white students. The reading gap is larger.

It's perhaps appropriate that what is marked today is the first march of three: there were many hard miles ahead.