'Radical Reformation': The hidden Anabaptist revolution and its message for struggling Western churches

While October 31st marks the 500th anniversary of the Reformation as the day when Martin Luther posted a list of grievances for discussion on the church door at Wittenberg, the elements that fuelled change pre-dated Luther's challenge.

Humanism and renewed attention to the biblical text, anxiety about some corrupt practices in the Church of Rome and political ambitions for territorial supremacy had swirled about the Papal See. Luther was the catalyst for change and seized the watchword of 'salvation by faith alone' - faith that came from God and not as the gift of any ecclesiastical body. Out of the process 'Protestant' entered the language.

Luther (and Calvin subsequently) used the civil powers to achieve their changes – princes and town council and the like. It was change from above. No where was this more obvious than in England, where reformation carried the added weight of Henry VIII's dynastic worries. The map of Europe was changed into Protestant and Catholic countries.

But there was another stream – the often overlooked 'Radical Reformation'. Groups of people read the bible and did not see church as a state-sponsored religious institution but the free association of men and women called together by God to live out Christian discipleship. Because they signified this intent by a second affusion of water baptism, they were known by their opponents as Anabaptists

Groups emerged in the 1520s and 1530s in several areas of Europe: German-speaking parts of the Holy Roman Empire, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Bohemia among others. They were believer communities, most of whom held pacifist views and practised communal welfare. Women were active as preachers, evangelists and martyrs.

State and Church alike reacted violently and Anabaptists were persecuted by Catholics, Protestants and Henry VIII. On the Continent, drowning was often thought an appropriate way of government sponsored execution.

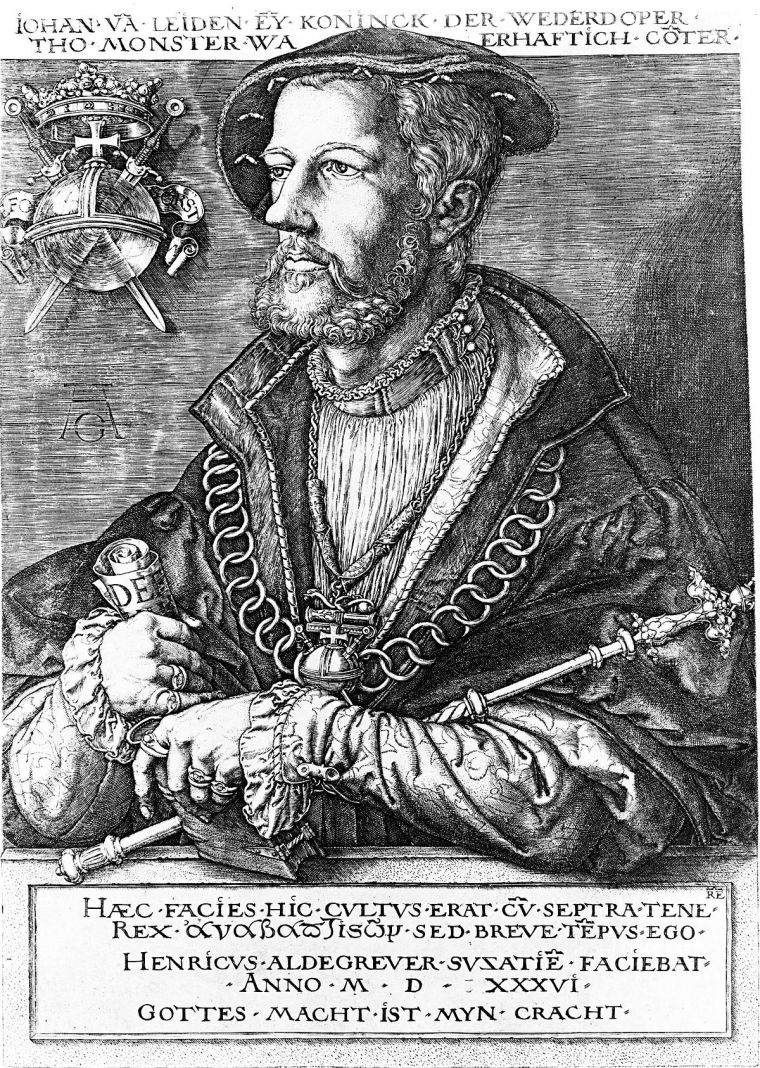

Anabaptists created an alternative church culture. They rejected the Constantinian model of the church, claiming the right to believe without state coercion or interference. They refused to pay tithes or taxes to support the state Church. Many refused to bear arms or accept the authority of the civil magistrate by swearing oaths. There was no overarching ecclesiastical structure nor leadership hierarchy but a confidence in Jesus encountered in the scriptures. Suffering was a mark of a true Christian community. These communities spawned both mystics and the apocalyptic revolutionaries of Munster, whose reputation echoed down into the seventeenth century as a warning of what would happen if religious radicals were not crushed.

Driven underground, and half-forgotten, with the current decline of Christendom in Western Europe, the possibilities of the Anabaptist way are there to be rediscovered - local communities of people committed to Jesus, comfortable with exploring life on the margins and shaping an ethical response in discipleship.