Martin Luther King Day: What his unfulfilled Dream has to say to the Church

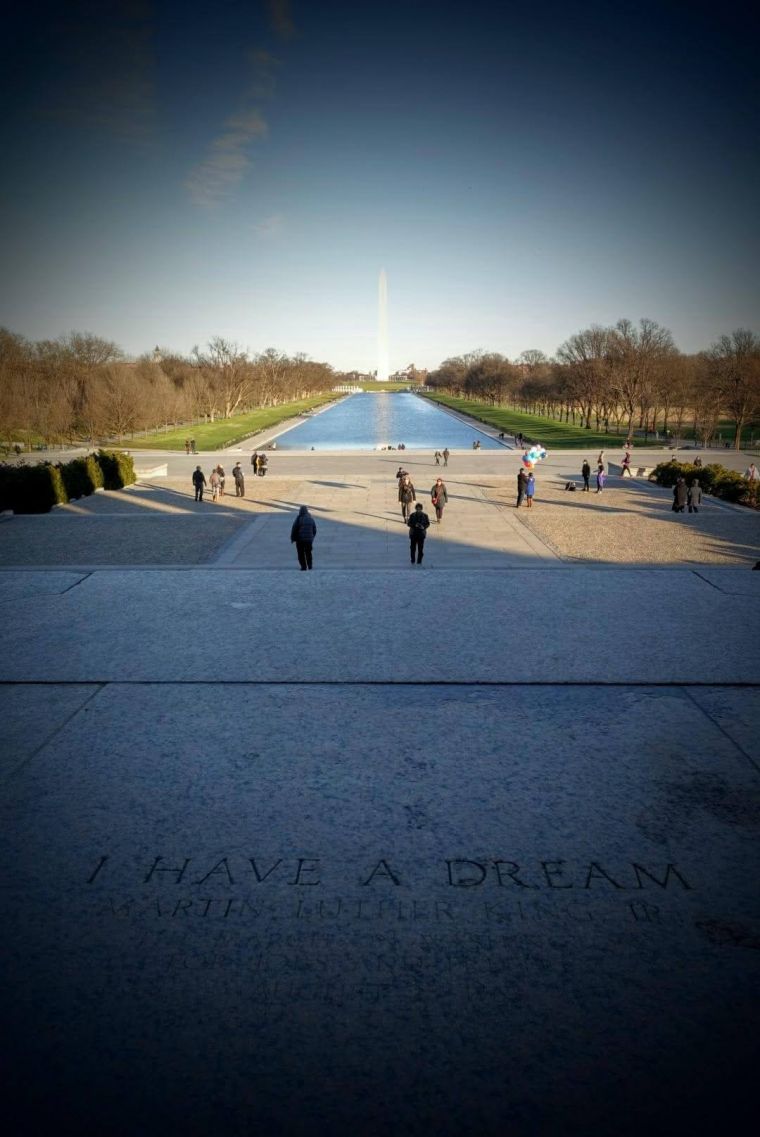

It felt like trespassing on holy ground, but there I was: stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, looking out across the waters towards the striking Washington monument. Apart from a couple of tourists with selfie sticks and the odd school group being shown around the sights, it was relatively empty on the crisp January afternoon. The only evidence that something world-changing had happened here were four words etched into the stone steps: "I have a dream." This is a beautiful, hushed part of Washington DC close to the river and far away from the shops, hotels, museums and government buildings that otherwise crowd the centre of America's capital city. In the stillness, I try and imagine that sunny day when Martin Luther King Jr addressed a crowd of a quarter of a million people gathered to hear what was to become arguably the most famous speech of the 20th century. With television and radio coverage, King's dream echoed around the world, not only that day but over and again for the following five decades and beyond.

The speech needs no introduction from me; it's become a significant part of mainstream culture. Even my children knew what it was when it was referenced during their Christmas boxset marathon of Friends:

Joey: "I kind of had a dream... But I don't wanna talk about it."

Chandler: "Whoa whoa! What if Martin Luther King had said that?"

It is a beautiful speech, well worth listening to as a Masterclass in communication. King used the call and response style of the black churches of America where he learned his trade as a Baptist preacher, but he connected it with the great speeches of America's history and racial strife that divided America on that day in 1963. He offered both poetry and polemics, political engagement and prophetic challenge. It was a speech and a sermon and a battle cry all rolled into one.

King would have been 86 years old today: his birthday is recognised as a national holiday in the United States, but it seems to me pertinent to commemorate the speech with a reflection on how King's dream is being fulfilled.

The paradox of the United States is that at the twilight of the second term of its first black president and with an annual national holiday to celebrate the birth of a civil rights leader who held no political office, there still needs to be a campaign called #blacklivesmatter highlighting the apparent injustice of the treatment of black people on the streets of America by police and security forces. It seems that 53 years after King's "I have a dream" speech, the US is facing up to the sad fact that it is still a dangerous thing to be black in America. The statistics are tragic and unrelenting: if you are a black man in the USA you are five times more likely to be shot by the police than a white man of a similar age. Young black men are nine times more likely to be shot by the police than an average American. A study undertaken by the Guardian revealed that in 2015 alone, 1,134 black men were shot and killed by police in the US. Despite making up just 2 per cent of the population, black men aged between 15 and 34 make up 15 per cebt of all deaths logged last year due to the use of deadly force by police.

These statistics come in a year when Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old black boy, was shot by police while carrying a toy gun, and police officers involved in the killing were cleared of all charges. There have also been mass protests after the shootings of Freddie Gray and Christian Taylor. Sadly, in the past few years, black women and girls have also been victims of death at the hands of police officers – including Aiyana Jones, Meagan Hockaday and Reika Boyd.

It seems that King's dream that his "four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character" is still some way from being realised.

The US' struggle with racial inequality is compounded when paired with heightened anxieties around immigration. In his campaign for Republican candidacy, Donald Trump has made outrageous policy proposals. In one written statement he called for a "total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country's representatives can figure out what is going on." He has also proposed building a 2,000 mile long wall between Mexico and America. CNBC estimated the cost of that wall as between 10 to 25 billions dollars to build, and as much as 750 million dollars a year to maintain. These policy proposals have seen Trump's ratings soar.

King dreamt of a racially diverse, inclusive society. He explained: "when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, we're free at last!'" He was inspired by hope, despite the suffering that his family had experienced. Contrast that with Trump's proposals which are driven by fear – despite all the wealth and power at his disposal.

So on this Martin Luther King Day we see on one hand a movement of people who believe things to be so desperate that a campaign proclaiming that black lives matter is necessary, and on the other a polemical campaign seeking to legitimise a xenophobic climate. With King's dream now seeming more of a fairytale than a reality, it's time for the US to recover its history, and live up to the promise of its past. As I traced the words "I have a dream" on those steps in DC, something struck me about the positioning of King as he delivered the speech. Behind me, and therefore behind King, was the 19 foot high, 28 foot wide, 159 tonne white marble statue of Abraham Lincoln. Talk about the weight of moral authority. It makes sense to me now why King started off his speech with the words:

"Five score years ago a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today signed the Emancipation Proclamation."

This was a deliberate reference to Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, which states: "Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." This allusion allowed King to draw on all the moral authority of the most famous speech in American history, which itself referenced the founding document of the USA – the Declaration of Independence.

King goes on to explain, "In a sense we have come to our nation's capital to cash a cheque. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." King's genius was to take the fundamental documents on which the United States was founded and use them to challenge the current injustice of racial segregation, all under the watchful eye of Abraham Lincoln. Like an Old Testament prophet, he called on his nation to honour God by living up to the promises it had made in the past.

As the world marks Martin Luther King's birthday, I believe it is time for the Church to hear his dream again – and not only in America. We need to move beyond admiring King's rhetoric or seeking to imitate his poetry, and play our part in bringing about racial and ethnic reconciliation wherever we have opportunity to act and influence. Those of us who believe – as King did when he quoted Isaiah 40 – in a God who will one day bring peace to the Earth, need to give the world a further taste of that now. King believed that one day, "every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places plains, and the crooked places will be made straight, and before the Lord will be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together."

These issues are not just ones that America has to wrestle with. Wherever we live in the world, racial reconciliation is a serious challenge. There are huge hurdles to be overcome on the issue of immigration because of the atrocities performed by jihadist terror groups who seem to be deliberately fanning into flame ethnic hatred. In these days of fear and increased xenophobia, we need to hear King's dream again. The Church has an important role to play here. As the multicultural, multiethnic people of God called to demonstrate the coming Kingdom, we need to model another way. It is interesting to hear some of the rhetoric coming out of the Anglican Primates meeting which has sounded more colonial and paternalistic rather than respectful and honoring of brothers and sisters in Christ. It is incumbent on Christians to show the world that not only are all human beings equal because they are made in the image of God, but more than that, for Christians our identity of being connected to Christ means that all other allegiances are secondary. In Christ the colour of our skin, the socio-economic group we are part of, the country on the front of our passport or our political affiliations must never undermine our primary identity as sinners saved by grace and called into fellowship with our Triune God and with one another. It is time for our churches to reflect this reality – that we can no longer be divided by race, but instead need to model something of the coming Kingdom of God. Only then does King's dream have a chance of becoming a reality this side of the return of Christ.