Magna Carta: Pretty great, but I know a better one

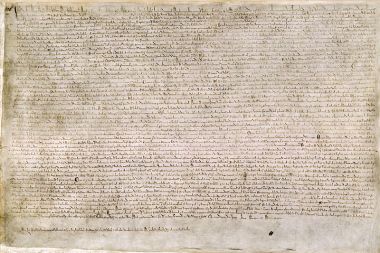

Today sees the 800th anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta.

On June 15, 1215, a recalcitrant King John – by some distance the best argument in history against a hereditary monarchy – was forced by a group of powerful barons to sign a document limiting the powers he had so grievously abused.

During the years since, the Great Charter has come to stand for the fundamental freedoms of English, then British, law. It has taken on an iconic status which is not at all affected by the quibbles of historians who say that it wasn't all that great, really, and was really about aristocrats securing their own privileges. Sellar and Yeatman had a subversive take on it in 1066 And All That: according to them, it said among other things:

That no one was to be put to death, except for some reason – (except the common people)

That everyone should be free – (except the common people)

That the Barons should not be tried except by a special jury of other Barons who would understand.

There is a good deal to be said for this reading. However, regardless of its actual provisions, the Charter really was a defining moment in what was to become democracy, in that it marked the point at which the King's subjects, or some of them, set formal limits on the power of the King.

The Church had a bigger part to play in all this than we had realised. It's been widely reported today that the bishops under Archbishop Stephen Langton – an unsung hero of reconciliation and resistance – took steps to ensure that the Charter wasn't just quietly ignored or binned. They placed their own scribes within the king's civil service to make sure that enough copies were made. According to the University of East Anglia's Professor of Medieval History, Nicholas Vincent, "King John had no real intention that the charter be either publicized or enforced. It was the bishops instead who insisted that it be distributed to the country at large and thereafter who preserved it in their cathedral archives."

He continued: "This serves as an important reminder of the ways in which our modern ideas of freedom, democracy and the rule of law emerged from a close co-operation between church and state."

Well, quite: but it should not be assumed that the bishops were acting from altruism. The first paragraph of the Charter is a royal guarantee of the rights of the Church: "We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, for Us and our Heirs for ever, that the Church of England shall be free, and shall have all her whole Rights and Liberties inviolable." So making sure that the Charter was well publicized was enlightened self-interest as much as anything else.

But the other thing about that particular clause is that it's one of the only three that still have legal force. The others are about the rights of the City of London and other towns and ports, and the famous Habeas Corpus provision: "No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right."

The latter, at least, has a ring to it that confounds cynicism. It's impossible to believe that those who wrote that clause didn't believe they were doing something significant.

Magna Carta is 800 years old. It still speaks to us as citizens – and indeed, its call for justice has gone around the world. It has subtly and profoundly shaped Western ideas of democracy and the value of human life in ways that we are still learning to recognise. And most of it is a dead letter, of no more intrinsic use than any other 800-year-old legal document.

As Christians, we look to an even older book for our values and beliefs. We believe it was written by inspired individuals over many centuries. It is interpreted and re-interpreted afresh in every generation. At different times, different parts of it speak with fresh meaning. We learn more about it all the time, and it never loses its power to challenge, to comfort and to teach.

Magna Carta means "Great Charter", as David Cameron famously didn't know when asked the question on a US talk show. The Bible is an even greater Charter, and it will outlast every human document, even this one.

Follow @RevMarkWoods on Twitter.