Magazines show a village at war

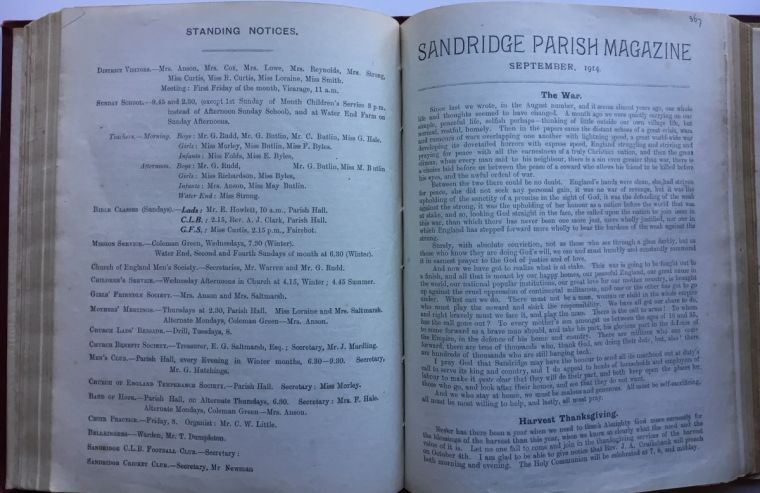

Parish magazines published in a Hertfordshire village from 1914 to 1918 reveal poignant insights into life in the rural community during the First World War.

They also show how, a century ago, one of my predecessors as a Christian minister in Sandridge parish, just north of St Albans, supported the war effort.

The magazines tell the story of how the men of Sandridge village responded bravely to the call to arms and how those left behind gave their backing on the home front. The pages record the deaths, the missing, the injured and those taken prisoner – and also the rejoicing as the war came to an end 100 years ago this Sunday.

Rev Hugh Anson, who was vicar of St Leonard's, Sandridge, throughout the conflict, wrote of Armistice Day, November 11, 1918: 'We assembled solemnly and joyfully in church to render thanks to the good God, who has preserved our land and protected our homes, and has given the greatest victory in all history to the cause of justice and honour and truth.'

Anson also recalled those who would not be joining in the celebrations: 'Glorious is the memory of those heroes by whose sacrifice the victory has been won.' He added: 'The hearts of many were overflowing with thanksgiving for the loved ones who had been through the great struggle, and might now come back to their homes again.'

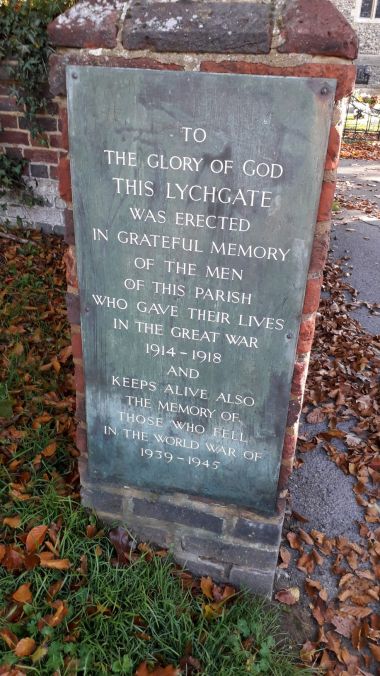

The lych gate outside St Leonard's church was erected after the First World War as a memorial. It lists 24 men from the village who were killed. Two further casualties are buried in Commonwealth War Graves in the churchyard.

Twenty-six Sandridge men from a population of 820 died in the war – a sign of how the conflict impacted communities across the country. Unusually, the lych gate also records the names of around 130 men from Sandridge 'who served and returned from the Great War'.

After the Second World War, the names of five other local men who were killed in that conflict were added.

In each month's edition of the magazine throughout the Great War, Hugh Anson penned a message to his parishioners. At the outset, he wrote: 'Every mother's son amongst us between the ages of 18 and 35 should come forward as a brave man should, and take his part, his glorious part in the defence of the Empire, in the defence of his home and his country.'

As the war progresses, the magazine records how the church launches appeals to send Christmas gifts to soldiers from the village serving at the Front. Local schoolchildren knit mittens for the men on active service. The vicar encourages his parishioners to invest in war bonds, to conserve food and burn less coal – and to be careful how they welcome home soldiers on leave.

He warns in August 1915: 'We shall, from time to time, be having soldiers home from the Front, perhaps wounded soldiers. Let us respect and honour them for all they are doing and suffering, but let every man amongst us stand up and protect them from the unpatriotic action of any, who by treating them, would play upon their weakened nerves, and lead them into drink.'

Many of the soldiers keep in touch with the vicar. In June 1916, the magazine reports: 'Their cheerfulness and pride in doing their duty is magnificent, and among all the letters the Vicar has received there have been hardly any complaints or grumbling.'

Just over a year later, after several new casualties among village men, Anson writes: 'A cloud has passed over Sandridge this last six weeks, and the sacrifice is costly and our hearts are heavy. But we know that every one of our brave soldiers is ready to give his life for his country. – the glory is theirs, the sorrow ours.'

The parish magazines show how Anson tirelessly kept going a wide range of parish activities in addition to conducting christenings, weddings and funerals and leading services of prayer and worship.

This Sunday, at 10.45am, an Act of Remembrance will be held at the lych gate by St Leonard's Church, Sandridge to commemorate those who died in the First World War, and in wars since then.