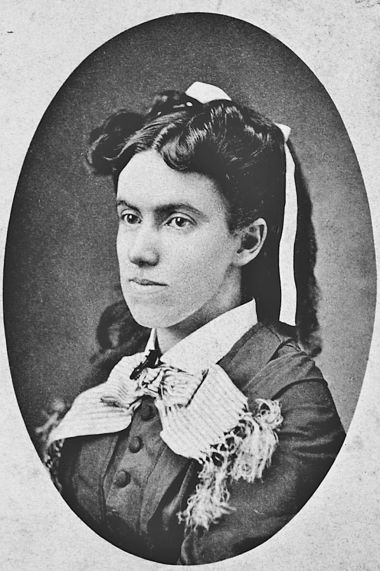

Lottie Moon: the fiercely independent missionary who broke the rules

Charlotte Moon was born in 1840 to a plantation-owning family in Virginia, in the pre-Civil War southern culture depicted in Gone with the Wind. Her family were committed to women's education and Lottie, as she became known, was well educated at college in languages.

After a youthful rebellion against Christianity, she was converted in 1859. A woman well under five-foot in height, Lottie spent the Civil War helping her widowed mother manage the estate and teaching in schools.

Lottie began to consider missionary service. Her denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention, struggling not just with Scripture but also with what was 'proper' for 'southern ladies', had been reluctant to take single women.

However, in 1872 they accepted Lottie's younger sister as their first single woman missionary and Lottie soon felt called to follow. She was accepted in 1873 and joined her sister in north China where she was put to work as a school teacher, a role that she soon found unfulfilling.

Soon, with excellent fluency in Chinese, Lottie felt called to be an evangelist and church planter. However, her mission's policy prohibited a woman from preaching to groups which included men. Never one to suffer quietly, Lottie began writing letters and articles, many of which found their way back to the United States. Pointing out the shortage of missionaries and the extraordinary evangelistic opportunities available in China, Lottie pressed for women to be allowed to use any gifting they had for evangelism or preaching. It was not a popular view and Lottie found herself widely criticised.

Eventually, Lottie ignored the mission board's ruling and, operating in a relatively remote area of China, began preaching to everybody, whether they included men or not. Her argument was that she had no option because there weren't enough men obeying Christ's command to evangelise the world.

At this time Lottie also faced a deep personal challenge. In America she had developed a close friendship with Crawford Toy, a theologian and linguist. Considering his proposal of marriage, Lottie realised that not only would it mean that she would have to leave China but that her fiancé's faith was increasingly drifting from traditional Christianity. Forced to choose between God and love, she chose God. The relationship ended.

Lottie now turned to full-time evangelisation in the interior. She lived alone in a small Chinese town, adopting everything of Chinese culture that wasn't in contradiction to Christianity and developing her own innovative ways of preaching. The fruit was remarkable and she saw hundreds of converts and numerous churches begin.

Faced with shortages of workers and funds, Lottie made appeals to her readership in the United States. The result was the creation of the Woman's Missionary Union within the Southern Baptist Convention to specifically focus on the support of mission activity. Acting on Lottie's suggestion, in 1888 the WMU proposed that a Christmas offering be made for foreign missions; it became a yearly event.

As the years passed, Lottie, with her understanding of the language and culture of China and extraordinary record as a church planter, became someone who could not be ignored within the mission. She demanded that women missionaries should have equality when it came to making decisions. Of lasting significance was her insistence that missionaries should maintain much closer and, through regular home assignments, more lasting links to their sending churches.

Plague, famine and various wars and rebellions shook China from 1894 to 1911 but Lottie continued her programme of church planting and discipleship. With the new century, her physical and mental health began to fade, something made worse by the way she gave away her food to needy families. After 40 years of mission work in China, Lottie returned to the United States, but she died at sea on Christmas Eve 1912 at the age of 72.

Lottie had an impact well beyond her own place and time. Let me suggest three heroic qualities that have had an effect.

First, Lottie showed a challenging independence in mission. There is an amusing irony in the way that someone who so persistently and impatiently made her own mission so uncomfortable ended up as one of its iconic figures. But the fact is that, irrespective of the rulings imposed on her by those above her, Lottie constantly did what she felt called to do by God.

Second, Lottie Moon had a compelling impact on mission. Lottie achieved much in China but her biggest influence was with her church community in America. She encouraged churches to focus on missions, promoted much closer and more sustained links between churches and their missionaries, and did much to ensure that missions were adequately resourced by personnel and funding. The remarkable success of the Southern Baptists on the mission field in the decades that followed owes much to the way that Lottie Moon so forcibly put missions high on their denominational agenda.

Finally, Lottie Moon became a continuing inspiration to do mission. Whether as 'the reality' or as an individual enhanced by legend, Lottie Moon has inspired and motivated generations of individuals to go live, and sometimes die, on the mission field. That's quite an achievement. The Christmas appeal for missions which she started, became from 1918 The Lottie Moon Christmas Offering for Foreign Missions. By 2021 it was estimated that over the years it has raised a total of five billion dollars for global mission.

There's always a danger when someone becomes a legend that we are misled because myth has over-ridden truth and fiction overtaken fact. What is fascinating with Lottie Moon is that the reality is every bit as impressive as the legend.

Canon J.John is the Director of Philo Trust. Visit his website at www.canonjjohn.com or follow him on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.