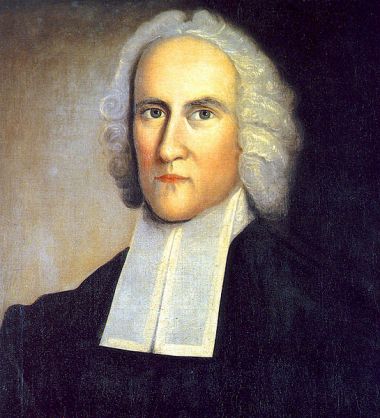

Jonathan Edwards' disturbing support for slavery: some reflections

The American theologian Jonathan Edwards has had a huge influence on Christians on both sides of the Atlantic.

The works of the 18th century preacher continue to be widely read; the well-known US pastor John Piper and prominent UK minister Martyn Lloyd-Jones have been among those in recent decades shaped by his writing.

Yet there is a darker side to Edwards which is not so well known: the fact that he owned slaves. Indeed, he did so throughout his life – and although he modified his views a little, he continued to support the idea of slavery. In the light of all that has been happening both in America and Britain in recent weeks, this will give many of us pause for thought. And it may come as a shock to those who knew nothing about it.

Historical records show that in 1731, Edwards visited Newport, Rhode Island, where he purchased Venus, a black girl thought to have been an African who was about 14-years-old. Over the years he and his wife Sarah are believed to have acquired five more – Leah, Joab, Rose, Titus, Joseph and Sue. Such slave ownership was common among elite New Englanders of the time, so Edwards was not unusual in this regard, though that doesn't of course excuse it.

In terms of his own treatment of slaves, Edwards adopted what he seems to have believed to be an ethical approach, writing: 'If I despise the cause of my man or maidservant when they plead with me, and when they stand before me to be judged by me, what then shall I do when I come to stand before God to be judged by him? If I despise my servant's cause, how much more may God despise my cause?'

Over time, his views shifted a little, but not hugely. The Massachusetts Historical Review (2002) states that Edwards 'came to oppose the overseas slave trade... but defended slavery as an institution and did not free his remaining slaves.' The evolution of his thoughts on international slave trading appears to have been shaped by a belief that it hindered the spread of the gospel.

Whatever the nuances of Edwards' views, the fact that he owned slaves at all is profoundly disturbing for us as Christians today. It was not even as if everyone who shared his theology at the time also supported slavery – some didn't. Even before Edwards, English theologian Richard Baxter had condemned it. So what should we make of it all?

Apart from anything else, it reminds us that all theological heroes have feet of clay. That is because we are all sinners. This should not surprise us – after all, when we look at the Bible we see that some of those most greatly used by God (Abraham, Moses, David, to name but a few) were also hugely flawed. The gospel is not for perfect people – it is for imperfect people who recognise they fall short. When we idolise any human preacher – whether it is Billy Graham, Don Carson, Dick Lucas or Nicky Gumbel – we are setting ourselves up for disappointment.

Edwards' slave ownership also challenges us about our own blind spots. We live in an age where most people – Christian and non-Christian – seem to believe they are 'right' while everyone else is 'wrong'. And in online echo chambers, our self-righteousness about our cause is reverberated, magnified and reinforced.

But the likelihood is that you and I – whatever your views on all manner of things – are spectacularly wrong about some matters. That may not be because we are thoughtless, if we are Christians, in seeking to understand Scripture, or sloppy in our exegesis. It may just be a product of our own sinful shortcomings and cultural contexts.

And this in turn should lead us to a certain humility, perhaps. As Jason Meyer has written: 'If Jonathan Edwards could succumb to such obvious, woeful oppression and injustice and theological hypocrisy, then we should be spurred on to greater levels of self-examination. Where are our blind spots? Or where do we wilfully turn a blind eye to things we're simply afraid to address?'

For all of us, it is never too late to change our views on anything as we continue to reflect carefully on Scripture. John Newton, author of the hymn Amazing Grace, denounced slave trading in 1788, a full 34 years after he had retired from involvement in it. He apologised for 'a confession, which ... comes too late' and added: 'It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.'

So, never mind the sins and blind spots of others right now – what about our own, especially when it comes to race?

David Baker is an Anglican minister and journalist @Baker_David_A

Views and opinions published in Christian Today are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the website.