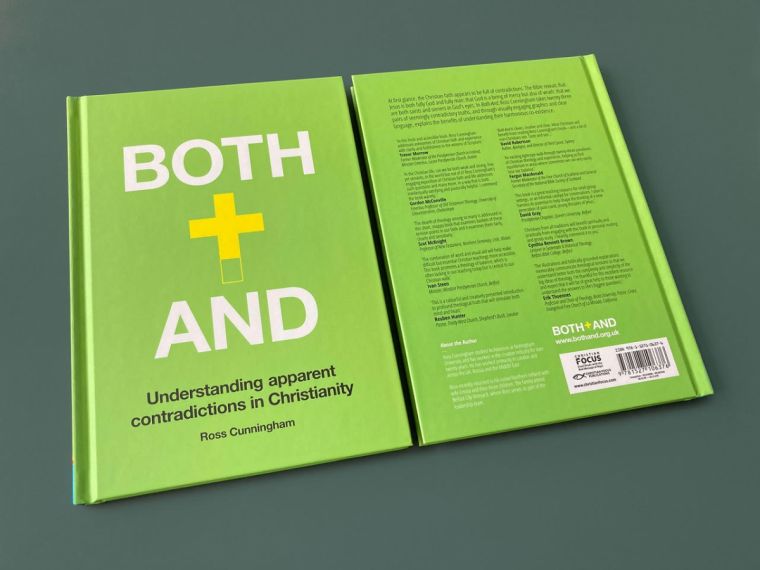

Is the Bible full of contradictions?

At first glance it can seem like God's Word is full of contradictions, but in his new book "Both-And", Ross Cunningham explains how all of the apparent paradoxes in the Bible can beautifully co-exist.

Ross speaks to Christian Today about what inspired him to write the book and how we can make sense of some of the apparently contradictory aspects of the Bible.

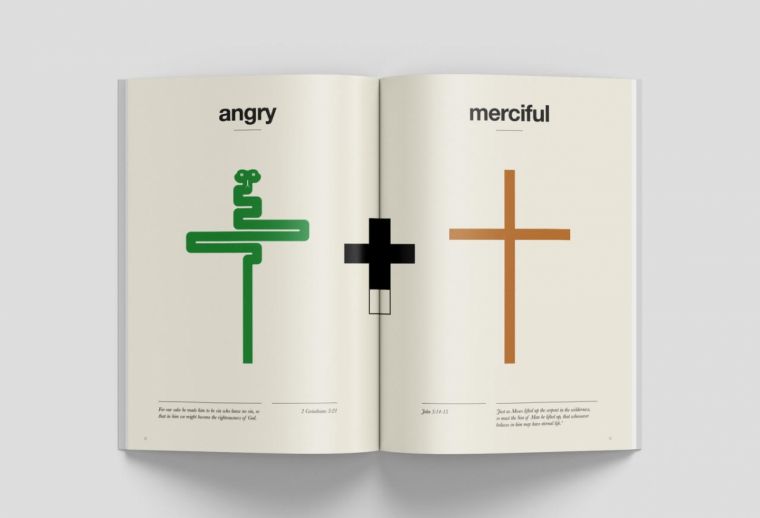

CT: One of the contradictions you seek to unpack in your book is God as both "angry" and "merciful", an idea that a lot of non-believers struggle with. You write that we "can't sugarcoat the reality that God is angry at us". What do you think we lose if we downplay the reality of that anger?

Ross: I think it disrupts both the justice of God and the grace of God. His righteous anger at sin — at what is broken in his creation — is what makes his salvation for us especially amazing. If God was calling us to return to him, and his anger was simply waived, then it would minimise the grace on offer.

The truth is that God's anger is righteous; he has the right to be angry at us and at our sin. We are the reason his creation is groaning. Yet the unexpected grace we see on the cross is that he shields us from that very anger through Christ. His wrath is willingly taken by Christ on our behalf.

It seems like anger and mercy are a contradiction and can't possibly go together, but they are both necessary components of a just God. God himself takes the wrath we deserve, and we receive his mercy. Amazing grace!

CT: You argue that it's a misconception to differentiate between the 'God of the Old Testament' and the 'God of the New Testament', as if they are not the same God. Why do you think that is a misconception?

Ross: I think a lot of people grow up learning 'Bible stories' and then, perhaps inadvertently, think about some of the harsher stories in the same way that we might think about mythical childhood stories, like Little Red Riding Hood, for example. If we feel confused or even horrified by the severity of some of these stories, we tend to relegate them to the sphere of folklore, rather than historical account. And so, because of the harsh reality of many of the Old Testament accounts, I think we're naturally in more danger of mythologising the Old Testament in our thinking.

And of course, there are harsh lessons in it — the Israelites seem to be in a washing machine cycle of getting things wrong and experiencing God's anger and judgement as a result of their failings. But it just takes a little bit of unpacking to see that there is a perfect continuity between the Old and the New Testament, and to see that it's the same God throughout.

I think we can understand this best through the idea of covenants.The covenant of grace, initiated by God all the way back with Abraham in Genesis, is the same covenant of grace that we enter into with him today. The new covenant, that Jesus fulfils, is just the last and final update of the same agreement. So God's grace is clearly not just a New Testament concept (in the same way that his anger cannot be neatly apportioned to the Old). We perhaps just see his grace more easily in the New Testament because Jesus lives it out for us in person. But, with a little investigation, we can see that all aspects of God's nature (anger, love, mercy, grace, goodness, justice etc) are all present throughout the entire narrative of the Bible.

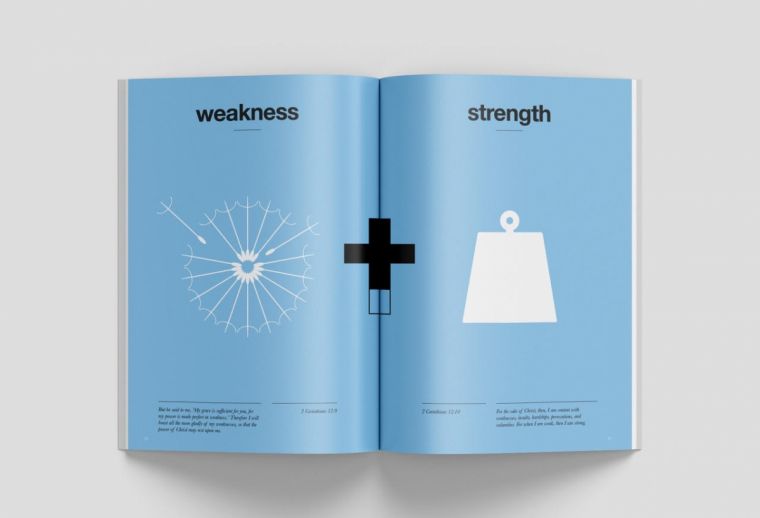

CT: You warn against "the caricature of the always happy, best-buddy Jesus". Why is there no contradiction in the coexistence of both sorrow and joy in the life of the Christian?

Ross: I think the coexistence of sorrow and joy is made most evident in the face of suffering, especially from big events like Covid, and all the related physical, emotional and financial suffering we've collectively experienced in the last year.

Suffering, of course, can come into our life from so many different directions; sometimes from forces like Covid that we can't fully control, sometimes at the hands of others, or by our own actions, or even just as a result of the natural decay of our human bodies.

In the case of Covid, for example, there are those who would be quick to say that this pandemic is a judgement of God. But to suggest that God is using Covid to judge humanity, or even to judge a particular group of people, or a particular sin, seems way too general.

However, we also need to keep a category in our thinking that God could use Covid as a judgement for some. The Bible is repeatedly clear that God can use even something awful (plagues, snakes, famine, crucifixion) to help wake people up to the reality of their sin — of what's really going on in their own hearts. It's important to know that God can redeem and refine us through trials, even though he takes no pleasure in the pain and suffering we experience in the process.

Paul, in his letters, is helpful here because he wants us to know that both sorrow and joy are important in our growth in Christ. He writes that, thanks to his faith in Christ, he's been able to deal with the ups and downs of life. To find peace. He reminds us that circumstantially, we should expect hardship but, crucially, that God is always there with us, in both the highs and the lows, in the valleys and on the mountaintops.

I think that's a more helpful way to approach the bigger question of why God allows us to experience sorrow at all (whether from a pandemic or any other circumstance) — to know that God is in it with us, and that he can use even hardship and suffering to bring forth his good purposes for us.

CT: That seems almost counter-cultural - or at least counter-intuitive - in our society today, where our highest pursuit seems to be focused on achieving happiness. Even as Christians, we can struggle with bad things happening in our lives.

Ross: I think it's so culturally ingrained to pursue happiness that we can feel down if we're not constantly in good form. This only serves to rob our joy further because it becomes a cyclical process — we're sad because we're sad, and so on. But something helpful that I realised in the writing of this book is that sorrow should be an expected part of our existence, whether we're Christian or not. It's not that the Bible commands us to pursue sorrow, but Paul does tell us in Romans 12:15 to "rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep". From that verse alone, we can see that sorrow should be a natural part of our response to this broken world.

Jesus models this perfectly in John 11:35 where we read simply that "Jesus wept". This was in response to the death of Lazarus where Jesus shared openly in the mourning of his friends. When we share our sorrows in this way they tend to be reduced. Thankfully the reverse is also true: when we share our joys they tend to be magnified. Maybe it's in that sense that one day, in perfect union with Christ, all our sorrows will be swallowed up in joy.

CT: The book seems to be perfect for someone who knows a bit about Christianity but has decided it's not for them, or an ex-Christian who left the faith precisely because of these apparent contradictions. Is that who you had in mind when you started to write it?

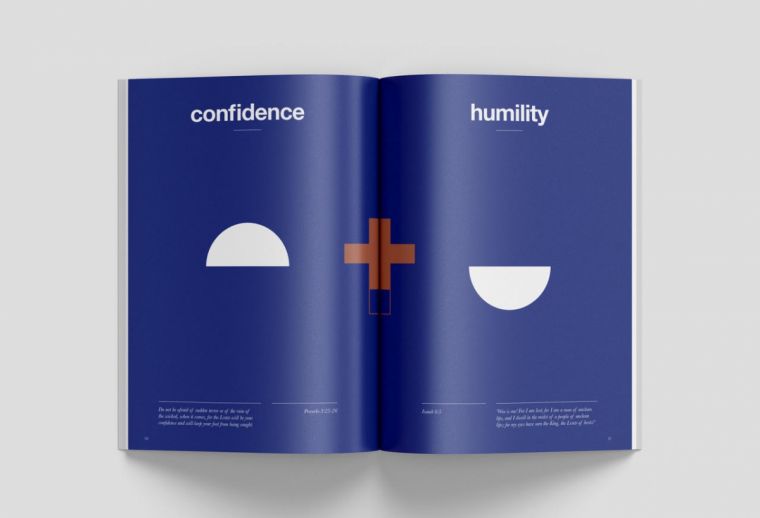

Ross: In some ways I was initially writing it for myself because I was lay-preaching at the time and was very conscious about the need to present a balanced view of whatever theology or doctrine I was speaking about. It's great to preach about God's holiness, for example, but if that teaching isn't counterbalanced with his intimate care for us, people's apprehension of God can quickly go askew or become too one-dimensional. The same is true for God's sovereignty and our human agency, which has so much application in teaching on prayer, evangelism and belief in general.

When I started to see the value of this 'both-and' framework of thinking I began working on the book. From that point it was largely written to another Christian (or in a more corporate sense, to the Church).

Certainly some of the chapters (like 'Faith + Reason' for example) are more apologetic in nature, so I think the book could be useful for non-Christians too. However, it's definitely not too heavy on the philosophical, historical or scientific side of apologetics.

My starting point is already that God exists and that the Bible is true. From that point I'm trying my best to explain some fundamentals of God's character and his amazing salvation plan for us. If I've managed to make that as compelling as it ought to be, then I believe it could be helpful for non-Christians too. To that end, I did try to 'de-jargonise' the book to an extent, but I do wonder if I went far enough with that endeavour.

Mostly I think the book will be a helpful aid for church leaders to teach Christians in smaller group settings. These Christians could be young or old in experience but, for whatever reason, haven't engaged deeply in theology yet. There's an accompanying study guide, free to download on the website bothand.co.uk which gives a helpful framework to explore the content chapter-by-chapter, with questions and worksheets.

CT: The whole book is about the apparent contradictions of the Christian faith. Have any of these contradictions been challenging for you personally? Or did you choose them because you could see that others struggle with them?

Ross: I wasn't aware of struggling with any of them in particular (though I'm sure I probably was and just didn't realise it). It might be one of those scenarios where 'you don't know what you don't know'. It's then easy to look back with hindsight and realise you were operating with an impoverished view of God. Thankfully for all of us though, God's mercy does not depend on our level of knowledge. In other words, we don't need a theology degree for him to choose us. Having said that, the great benefit of working through these paradoxes is that we come to understand better—and treasure more deeply—the One we're praying to; and, through that enhanced relationship, grow more fully in the characteristics required to be a blessing to others.

The book is currently available at the Evangelical Bookshop, Belfast, www.evangelicalbookshop.co.uk and from Amazon priced £8.99.