Has Charlie Hebdo crossed a line with its latest attack on Islam?

An English-language article in Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical magazine immortalised by the savage attack on it in January 2015, has drawn fierce criticism for linking the Brussels attacks with ordinary Muslims.

The article, 'How did we end up here?' says the attacks "are merely the visible part of a very large iceberg indeed. They are the last phase of a process of cowing and silencing long in motion and on the widest possible scale."

It cites the example of the thinker and broadcaster Tariq Ramadan, who lectured to students a fortnight ago on Islam at a prestigious French institution. "The little dent in their secularism made that day will bear fruit in a fear of criticising lest they appear Islamophobic. That is Tariq Ramadan's task," it says.

It imagines a burqa-clad woman who is "courageous and dignified, devoted to her family and her children"... "So why go on whining about the wearing of the veil and pointing the finger of blame at these women? We should shut up, look elsewhere and move past all the street-insults and rumpus." It also imagines local Muslim baker who doesn't use ham or bacon in his croissants. "So, it would be silly to grumble or kick up a fuss in that much-loved boulangerie. We'll get used to it easily enough... And thus the baker's role is done."

The article argues that "secularism is being forced into retreat". "From the bakery that forbids you to eat what you like, to the woman who forbids you to admit that you are troubled by her veil, we are submerged in guilt for permitting ourselves such thoughts. And that is where and when fear has started its sapping, undermining work."

Among critics of the article was Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole, who wrote: "Reading this extraordinary editorial by Charlie, it's hard not to recall the vicious development of 'the Jewish question' in Europe and the horrifying persecution it resulted in. Charlie's logic is frighteningly similar: that there are no innocent Muslims, that 'something must be done' about these people, regardless of their likeability, their peacefulness, or their personal repudiation of violence. Such categorisation of an entire community as an insidious poison is a move we have seen before."

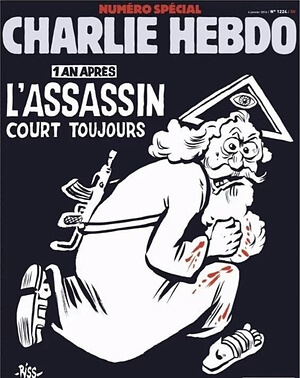

The attack on Charlie Hebdo has to a large extent insulated it from questions we would otherwise automatically ask of an article like this. "It's Charlie Hebdo, they have a right to say this," we think.

But anyone who goes into print with an opinion has to expect it to be challenged. And in the case of a piece that seeks to justify discrimination and hostility against people the authors themselves admit are perfectly innocent, challenging it becomes a duty.

The trouble is that Charlie Hebdo wants to see itself as a valiant crusader for truth, nobly proclaiming the most sacred values of the Republic. But it has never really risen to such heights. When it says: "It's not easy to get some proper terrorism going without a preceding atmosphere of mute and general apprehension," it's attempting to claim criticism of Islam is being stifled by political correctness. It's not; people are just being more polite.

Most of them, anyway. The decision by Marks and Spencer to sell 'burkinis', full-body swimsuits, was branded as misogynist by women's rights minister Laurence Rossignol, who said women in favour of it were like "negroes who supported slavery".

So Charlie Hebdo's brand of totalitarian secularism has its supporters. Well, fair enough: people should be free to criticise religion and no one should imagine for one moment that they can respond with bombs and bullets.

But freedom comes with responsibilities. You don't persecute or abuse someone just because they wear a burqa or because they won't make you a bacon croissant. They aren't the thin edge of the terrorist wedge; they're just folks. And people like Mme Rossignol have to realise that while she's perfectly entitled to her opinions, as a government minister she should not be abusing her position to impose a rigid secular conformity on a whole population. That is not political secularism, which is good – a level playing field for all ideas. It's doctrinal secularism, which is the dogmatic imposition of a religion-free ideology – and as wrong-headed as any other kind of fundamentalism.

What's pernicious about this Charlie Hebdo argument is just what Teju Cole says: it demonises a whole group of people for the actions of a tiny fraction of them. And yes, we have seen this before.

What's worrying, and sad, about the Charlie Hebdo article is that what happened in January 2015 lends its arguments a sort of spurious respectability. "These people know what they're talking about, after all," people think.

Well, no, they don't. They're speaking out of prejudice and ignorance, and they need to be called out.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods