Great Grinches through the ages - five people who've always hated Christmas

Everyone loves Christmas. It's a well known fact.

Like most such facts, though, it's not entirely true – just search "I hate Christmas" online and there is a startlingly comprehensive list of reasons why many people just don't get it. But who, in history, are the top five Christmas-haters of all time?

1. Oliver Cromwell (1599-1656)

It's not quite true that he personally banned Christmas – that was the elected Parliament – but when he took over as Lord Protector in 1653 he did his best to make sure that it stayed banned. The main reason was that it had become too popular and strayed too far from its Christian roots. It was a public holiday, and Puritans like Cromwell weren't keen on holidays anyway. They also weren't keen on over-eating, drunkenness and other forms of enjoyment, all of which featured quite heavily at Christmas. Added to this was its unfortunate name – Christ's Mass – which sounded a bit too Catholic for these extreme Protestants. So the Puritans, and Cromwell, ordered that it be kept as a solemn fast day (they also abolished Easter and Whitsun). Soldiers were ordered to go round the streets and confiscate food being cooked for a Christmas celebration, so the smell of a roasting goose could get you into real trouble. Oh, and you couldn't put up holly or mistletoe, either.

In the famous textbook 1066 And All That, Cavaliers were famously described as "Wrong but Wromantic" and Roundheads as "Right but Repulsive". Sometimes they weren't even right.

2. Philip Gosse (1810-1888)

He was the father of the famous critic Edmund Gosse and a noted scientist and naturalist. Gosse was another fierce Protestant who thought that Christmas was a Catholic invention designed to lead good Christians astray. ("The very word is Popish!" he would exclaim.) Edmund, in his book Father and Son, tells of one memorable Christmas. His father, of course, had banned it, but the rebellious servants made a small plum pudding for themselves, and out of pity for the child gave him a slice. His stomach and his conscience alike smitten, he went to his father and cried out: "Oh! Papa, Papa, I have eaten of flesh offered to idols!"

Let him take up the story: "Then my father sternly said: 'Where is the accursed thing?' I explained that as much as was left of it was still on the kitchen table. He took me by the hand, and ran with me into the midst of the startled servants, seized what remained of the pudding, and with the plate in one hand and me still in the other, ran till we reached the dust-heap, when he flung the idolatrous confectionary on to the middle of the ashes, and then raked it deep down into the mass. The suddenness, the violence, the velocity of this extraordinary act made and impression on my memory which nothing will ever efface."

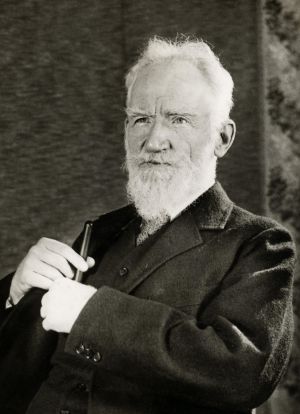

3. George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950)

A playwright, novelist, all-round thinker and founder of the London School of Economics, his well-known beard would have qualified him as a perfect Father Christmas if it were not for his views on the subject. He wrote in The World in 1893: "Like all intelligent people, I greatly dislike Christmas." He described it as "an atrocious institution", saying: "We must be gluttonous because it is Christmas. We must be drunken because it is Christmas. We must be insincerely generous; we must buy things that nobody wants, and give them to people we don't like; we must go to absurd entertainments that make even our little children satirical; we must writhe under venal officiousness from legions of freebooters, all because it is Christmas – that is, because the mass of the population, including the all-powerful middle-class tradesman, depends on a week of licence and brigandage, waste and intemperance, to clear off its outstanding liabilities at the end of the year. As for me, I shall fly from it all ..."

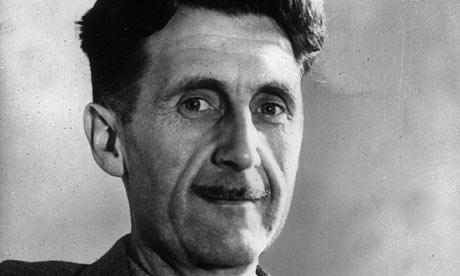

4. George Orwell (1903-1950)

The famous journalist and novelist was not the most cheerful of souls, and tended to look on the world with a rather jaundiced eye. He was not, however, opposed to Christmas in principle, though he saw it as "a debauch" – a chance for everyone to eat and drink as much as they possibly could, and hang the expense. In 1946, however, just after the end of the war, he wrote in a Tribune article of how inappropriate the whole thing was at that particular moment – not just in Britain, still rationed and poor, but particularly because of the state of the rest of the world.

"The world as a whole is not exactly in a condition for festivities this year. In India there are, and always have been, about 100 million people who only get one square meal a day. In China, conditions are no doubt much the same. In Germany, Austria, Greece and elsewhere, scores of millions of people are existing on a diet that keeps breath in the body but leaves no strength for work. All over the war-wrecked areas from Brussels to Stalingrad, other uncounted millions are living in the cellars of bombed houses, in hide-outs in the forests, or in squalid huts behind barbed-wire."

Gloomy stuff, and arguably right.

5. Ebenezer Scrooge (1843-)

The date is a bit of a cheat: that's when Dickens first published A Christmas Carol, which almost invented the modern Christmas. But the dash after it means that he is still alive today. And here he is: "Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grind-stone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster ... He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dogdays; and didn't thaw it one degree at Christmas."

No one any of us knows, surely – but a warning to us all. The story of Bob Cratchit, Tiny Tim and the sinner's redemption through the three Ghosts of Christmas is known around the world. What's sometimes forgotten, though, is why the story was ever written. The Children's Employment Commission had just exposed the terrible conditions suffered by children forced to work in the mines and factories of Britain's Industrial Revolution. Dickens had originally planned to write a pamphlet about it but changed his mind and wrote A Christmas Carol instead. So the two terrifying children who appear from under the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present, Ignorance and Want – "yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish" – are a solemn reminder of the consequences of neglect.

And a happy Christmas to you all.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter @RevMarkWoods.